PestFacts 6 April 2023

Bait snails now before egg lay

Snail populations

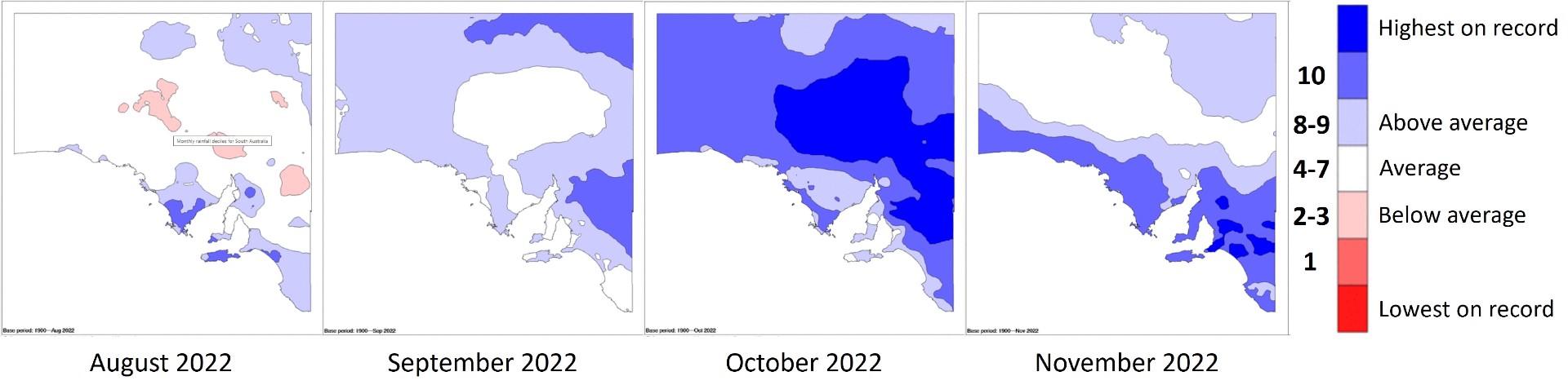

Reports suggest snail populations in parts of South Australia have been higher than usual in spring 2022 and during the 2022–23 harvest. The late winter and spring of 2022 was wetter than average in many coastal regions of SA, with rainfall deciles above eight recorded for all months from August to November (source: Australian Bureau of Metereology). Snails can breed from autumn to spring, but they typically lay most eggs early in the breeding cycle. The wet spring may have allowed breeding to extend later into 2022 than usual and increased the survivorship of juvenile snails.

SARDI Entomology’s observations in February and March 2023 suggest that refuges bordering paddocks, such as roadsides, pastures, or headlands, may have higher than usual snail numbers. It is important to monitor and bait fence lines to prevent snails re-invading paddock edges this autumn.

Tips for effective snail baiting

Round and conical snail activity has increased in parts of SA with recent rainfall and humidity. Now is the time to bait snails to kill adults before they breed.

The most efficient time to bait snails is at the end of their summer dormancy as soon as feeding activity begins. This is typically in late summer or early autumn, depending on weather. At this time, snails feed voraciously as they prepare to breed, they quickly metabolise bait toxins, there is limited alternative food, and fewer obstacles exist to obstruct pellet encounter (for example, crop seedlings).

The timing of bait application is critical to success. Snails must be moving and actively feeding to encounter pellets and ingest a lethal dose of toxin. Key points for successful baiting are:

- Monitor snail activity.

Snails move when moisture is present. In early autumn, relative humidity above 80–90% encourages movement. Overnight dew or light rainfall (less than 2 mm) increases relative humidity to 100%. Most movement occurs overnight between midnight to just after sunrise. To monitor movement, place bait pellets in a snail-infested area and check daily. The presence of dead snails around baits indicates snails are feeding, warranting widespread application.

- Apply bait at the right time.

Baiting before egg lay is critical. Apply bait when moisture is present (see above), and as soon as feeding commences at the end of summer dormancy. Snails breed from autumn to spring, but most eggs are laid by early winter.

If mice are present, bait mice before baiting snails to avoid mice consumption of snail bait. Mice have been reported across the Upper Eyre Peninsula. If mixed populations of round and conical snails are present, consider a second bait application around sowing time to target conical snails. The onset of peak activity can be several weeks later for conical snails than round snails.

- Monitor and re-apply bait as necessary.

Continue to monitor and re-apply bait as needed until around early winter. Baiting efficacy declines after this time. Baiting must cease at least eight weeks before harvest, as there is a zero tolerance for bait contamination of grain.

- Select an appropriate bait product.

Three active ingredients (and several formulation types) are registered for snail control in Australian crops and pastures: metaldehyde (15 to 50 g/kg), chelated iron (60 g/kg) and iron phosphate (9 g/kg iron). Choose a product according to your preferences. Consider the number of pellets applied per square metre at the registered application rate. Always adhere to directions on the product label. As a guide, use the snail and slug baiting guidelines () (updated baiting guidelines will be released soon). Refer to the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority Public chemical registration information system search for options.

- Apply an adequate rate of bait.

Pellet densities of at least 30 pellet points per square metre (up to 60 per square metre where snail densities exceed approximately 120 snails per square metre) are required to ensure an adequate chance of encounter. Re-apply bait as needed according to product label directions. Around fence lines may need higher rates or bait re-application.

- Broadcast pellets evenly using a calibrated spreader.

Always calibrate the spreader for the selected bait product to ensure an even spread. Uneven spread can result in poor efficacy. Manually check the spread width and drive at pass widths no larger than the effective spread width. See Lessons from the Yorke Peninsula to improve snail baiting effectiveness. The SnapBait app can assist with estimating bait pellets applied per square metre.

More information

- GRDC: Movement, breeding, baiting and biocontrol of Mediterranean snails

- Cesar Australia: Vineyard snail

- Cesar Australia: White Italian snail

- Cesar Australia: Small pointed snail

- Cesar Australia: Pointed snail

Fall armyworm update

Fall armyworm (FAW, Spodoptera frugiperda) is a noctuid moth from the tropical and sub-tropical areas of the Americas, known for long flights and voracious feeding by the larvae. FAW is a polyphagous pest and shows preferences for the Poaceae, and most commonly recorded from wild and cultivated grasses; from corn, rice sorghum and sugarcane.

Since its first detection in northern Australia in early 2020, FAW has migrated to other regions. Most recently, it has been detected in Victoria on maize over the 2022–23 summer (see Fall armyworm (and other moth larvae) in Victorian maize for more information).

There have been no detections of FAW in South Australia.

Trapping

Over summer, Adam Hancock (Elders Naracoorte) ran several pheromone traps in sorghum in the South East. The traps caught only one moth, which was identified by SARDI entomologists as southern armyworm (Persectania ewingii). These moths can easily be distinguished by the colour of the hind wing – it is white in FAW, and brown in southern armyworm.

The risk for SA

The only suitable development time for FAW in South Australia is January to March. From April onwards, parts of SA become unfavourable for population growth and by May all cropping regions are too cold – see Regional and seasonal activity predictions for fall armyworm in Australia.

Whilst FAW has a wide potential host range (greater than 350 known plant hosts), the crops of primary concern are corn and rice. FAW has also been reported on sorghum in Queensland. Summer cropping, particularly of corn, is at highest risk of fall armyworm damage. As the weather cools, we expect the risk of incursion will decrease.

Reporting fall armyworm

If you suspect FAW is present in your region, report it immediately to the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881.

Unusual caterpillars can be reported to PestFacts.

More information

- PestFacts March 2020

- GRDC Grains Research Update, online – Fall armyworm

- GRDC: Fall armyworm: what threat does it pose, and what tools do we have to manage it?

- GRDC: Fall armyworm

- Plant Health Australia: Fall armyworm

- The Beatsheet: Fall armyworm

Rutherglen bug and cotton seed bug reports

Rutherglen bugs (Nysius visitor) and cotton seed bugs (Oxycarenus arctatus) have been reported through the Mallee, the South East and across the Adelaide Plains.

Identification

Both species are hemipterans with a narrow body, prominent dark eyes, and piercing, sucking mouthparts. They are most often seen in swarms, particularly in spring and summer, with a mix of nymphs and adults.

Adult Rutherglen bugs are 3–4 mm long and grey-brown, with clear wings folded flat on their back. Nymphs are wingless and have a reddish orange, pear-shaped body, and the head is typically striped. See the Atlas of Living Australia Rutherglen bug photo gallery.

Adult cotton seed bugs are up to 3 mm long and have a black and white body, with a black patch in the middle of their forewings. Nymphs have a plump, bright red abdomen, a dark head and no wings. See the Atlas of Living Australia Cotton seed bug photo gallery.

Biology and control

Both Rutherglen bugs and cotton seed bugs are a highly migratory native species that are a sporadic pest typically seen in warmer months. They are very mobile and transfer between locations as harvest or host plants die down. They reduce in numbers over winter and aren't often associated with crop emergence.

The most successful way of reducing these bug populations is by controlling host weeds. Several organophosphates and synthetic pyrethroids are registered against them (see the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority Public chemical registration information system search), but these disrupt natural enemies and insecticide applications will not guarantee a clean crop as these bugs can readily reinvade a sprayed area. Several days of continuous rain can reduce populations.

More information

Cesar Australia: Rutherglen bug

Reduce pest movement with green bridge management

Managing the green bridge pre-season helps reduce the risk of early season pest and disease outbreaks.

What is green bridge?

The green bridge includes host plants, such as weeds and self-sown crops or volunteers, that provide refuge to various insect pests and diseases to survive between growing seasons.

The green bridge commonly grows along roadsides, in water courses, paddock perimeters, headlands and any other non-cropped areas of land. Early rainfall will increase the amount of green bridge. The presence and timing of green bridge is often critical in determining risks of early season pest and disease outbreaks in broadacre crops.

Green bridge management

For effective green bridge management in paddocks, control weeds early and ideally, well before sowing (at least four weeks prior, and for disease management purposes include the time taken for herbicides to achieve complete plant death). Relying solely on herbicides applied at or after sowing will often be too late to prevent movement of pests and/or diseases into emerging crops. Insecticides are not required for control as insects feeding on herbicide treated green bridge will starve as the plants die.

Green bridge can also harbour a range of beneficial insects, including ladybird beetles, hoverflies and parasitoid wasps that build up on pest populations. Consider the number of beneficial insects when deciding to control green bridge. Insecticide application on green bridge is not recommended, beneficials can often survive for a while without prey. Much cooler weather later in autumn can also dramatically reduce aphid populations.

More information

- GRDC: Diamondback moth best management practice guide – southern

- GRDC: Reducing aphid and virus risk

- GRDC: Green bridge factsheet

- GRDC: Green peach aphid best management practice guide – southern

- GRDC: Resistance management strategy for the green peach aphid in Australian grains

- GRDC: Aphid and insecticide resistance management in grains crops

Report to PestFacts

The PestFacts SA team always wants to know what invertebrates you find in your crops and pastures, whether it is a pest, beneficial or unknown – even the usual pests.

Please send your reports or identification requests via the PestFacts map.

Alternatively, please contact:

Rebecca Hamdorf

Phone: 0429 547 413

Email: rebecca.hamdorf@sa.gov.au

Maarten van Helden:

Phone: 0481 544 429

Email: maarten.vanhelden@sa.gov.au

The latest information for growers and advisors on the activity and management of pests in all broadacre crops during the winter growing season.