PestFacts 25 October 2023

Look out for beneficials in your crops

With a warm start to spring, beneficials have been active. There are several beneficial predators and parasitoid species that prey on crop pests, which can have a significant impact on pest populations.

You should only use insecticide when control by natural enemies or other factors is unlikely to prevent economic yield losses, and use 'soft’ chemicals when possible. Monitoring should include recording trends in beneficial populations.

How many beneficial insects are enough?

Currently, there are no predator to prey ratios that can guide management decisions.

However, there are some helpful guiding principles:

- Most beneficial species are highly mobile and will move from crop to crop if left unsprayed. There is often a time lag between the growth of pest populations and increases in the abundance of beneficials, particularly in the southern cropping systems during spring.

- Sometimes, beneficials will prey on pest species that are feeding on early crops before attacking other species during later growth stages.

- Monitor crops regularly so you can measure whether the number of beneficial insects (per sweep, per metre, etc.) is increasing (or not).

- Whenever possible, choose a specific pesticide that does not affect beneficials, instead of a broad-spectrum insecticide. Though it might be more expensive, the overall effect could help avert an increase in pest numbers.

More information on beneficial insects:

- Benefical insects – the back pocket guide

- I Spy – Identification manual and education resource

- Beneficials chemical toxicity table

Here are some beneficial groups found throughout south-eastern Australia:

Wasps

Several species of female parasitic wasp lay their eggs into aphids or caterpillars. The developing wasp larva either feed inside or from the outside of the host. Aphid 'mummies' – bronze-coloured, enlarged aphids – indicate the activity of parasitic wasps. Even with little mummies visible, parasitism can be quite high, simply because the mummy is only the very last stage of wasp development. Caterpillars parasitised by wasps often have larvae emerging and pupating around the dead caterpillar.

Many other species of wasps are also predatory, and we have received reports of potter wasps using armyworms and helicoverpa as prey for their young.

Ladybird beetles

Both larvae and adult ladybirds are voracious aphid predators. They also feed on leafhoppers, thrips, mites, moth eggs and small caterpillars.

Larvae are grey to black, have elongated bodies with orange markings and may be covered in spines or white fluffy wax material. As adults they are round to oval-shaped, with black spots on red, orange or yellow shells.

Hoverflies

Hoverfly larvae feed on a range of soft-bodied insects, particularly aphids. They are common in flowering crops and places where there is available pollen for the adults to feed.

Hoverflies are most noticeable as adults, when they have dark-coloured flattened bodies with black and yellow markings. They often hover around floral resources or aphid colonies. However, it is hoverfly larvae (a greenish or cream maggot) that is predatory, often found in aphid colonies. As larvae, they are often mistaken for pest caterpillars such as diamondback moth but lack the typical head capsule of caterpillars.

Lacewings

Lacewings are voracious predators and will eat a wide variety of insects including aphids, thrips, mites, caterpillars and moth eggs. Only the larvae of green lacewings are predatory, but with brown lacewings, both larvae and adults are predatory, and brown lacewing larvae can eat 100 to 200 aphids during their lifetime.

Lacewing larvae have protruding sickle-shaped mouthparts and a long body shape that varies from thin to stout. Some species will carry the exoskeletons of their prey on their back as camouflage. As adults, they have prominent eyes, long antennae, and large clear wings with many veins, giving a lacy appearance.

Damsel bug and predatory shield bugs

Predatory bugs are typically found in the canopy of crop plants, feeding on a range of soft-bodied prey including small caterpillars, moth eggs and aphids.

Damsel bugs have a slender light-brown body with long antennae and large protruding eyes. They have a long curved 'snout' they carry under the body when not feeding. There are several species of predatory shield bugs that vary in size and shape. Early instars start out bright red but change to dark red and brown as juveniles. Adults have shiny, shield-shaped bodies, often with patterns and spikes.

Spiders

A wide range of spiders are common in the broadacre environment and are generalists.

Predatory beetles

Many species of ground (carabid) and rove beetles are voracious generalists common in crops. They feed on a wide range of species including aphids, mites, caterpillars, and various other insect eggs. Some species even feed on snails and slugs.

Predatory beetles in general have large forward-facing mouthparts. Although their body shapes and colour can vary, most ground beetles are shiny black or metallic and have ridged wing covers. Rove beetles range in size, but many species are very small and their wing covers are short with some abdomen showing,

Earwigs

You might consider European earwigs to be a pest as they nibble on plants and kill seedlings; but they are also good predators of aphids! In later growth stages of the crop, they are considered a beneficial insect. You will often find earwigs hiding during the day in the rolled leaves of cereals, and nocturnally consuming aphids. Native earwig species aren’t known to damage seedlings and are a beneficial insect but rarely show high populations in crops.

Monitoring slugs in spring for future management

Slugs are typically found in zones where annual rainfall exceeds 500 mm. However, black keeled slugs can be found in medium rainfall areas where rainfall exceeds 450 mm, especially after a couple of wetter seasons. Crops are particularly vulnerable to slug damage at establishment. However, monitoring in spring provides a good opportunity to assess slug numbers and distribution in paddocks, which will assist preparation for managing slugs next year.

Monitor this spring to understand your 2024 establishment risk

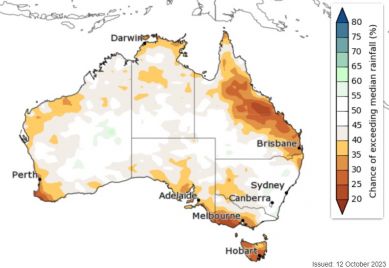

Favourable conditions over the past 3 years have led to a build-up of slug numbers in slug prone areas. Reports this season have suggested unusually high numbers, and some expansion into areas not traditionally affected (see PestFacts 28 July 2023). However, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) has declared that an El Niño is underway and current outlooks suggest a drier spring and summer, meaning less favourable conditions for slugs.

Slug activity can be monitored with refuges (for example, carpet mats or tiles) placed in paddocks and checked in the morning. As slugs often have a patchy distribution in paddocks it’s important to use multiple refuges. Fifty monitoring refuges are recommended when paddock size is greater than 40 hectares. Monitoring is encouraged in wet conditions when slugs are active.

If you detect high numbers of slugs in your maturing crops, control options are limited. Current research does not recommend springtime baiting intended to reduce slug numbers for next season. Long harvest withholding periods, up to 8 weeks, further limit when baits can be applied to maturing crops. Monitoring during spring provides an understanding of population dynamics for estimating the risk of possible establishment issues next season. Baiting should be done in autumn, after sowing, to protect seed and emerging crops.

Slug resources available

Best practice management of slugs requires an integrated approach. Rainfall estimates and spring monitoring provides key information to assess risk for 2024 and helps to make informed management choices.

More information on slugs in broadacre agriculture:

- Slug control fact sheet: Successful crop protection from slugs (PDF 3.5 MB)

- Slugs in crops: The back pocket guide

- Slugs – what can we learn from 2022

- Slug control across southern Australia

- Black keeled slug

- Grey field slug

Black Portuguese millipede movement

Black Portuguese millipedes (Ommatoiulus moreletii) have been reported migrating in high numbers along crop edges, especially after rain.

This migration can sometimes cause issues, especially as a nuisance pest that can invade homes and sheds. Millipedes favour conditions around 17°C to 21°C and 95% humidity, and so are more likely to be seen moving then. As temperatures increase and moisture decreases millipedes will likely look for refuges to avoid hot and dry conditions.

The risk for crops at this stage is low as black Portuguese millipedes are mainly detritivores, meaning they feed on dead organic material. They can be a contamination risk if moving around during harvest. As they are mostly active at night, consider harvesting during the heat of the day to reduce contamination risk where high populations occur.

Keep an eye out for faba bean aphid

The exotic faba bean aphid (FBA, Megoura crassicauda) was originally detected in New South Wales (NSW) in 2016 and has slowly been reported throughout parts of south-eastern Australia (see PestFacts November 2022: Faba bean aphid movement for an overview).

So far, growers have not detected this aphid in South Australia but it is likely to spread into our state following colonisation in Victoria. Growers and agronomists are encouraged to implement and maintain good on-farm biosecurity measures and be vigilant for unusual pests or disease symptoms in crops.

Report suspect observations immediately to the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881.

Biology and potential impact

There is limited information about this aphid in field conditions in Australia. Research is currently being undertaken in eastern Australia. Recent reports from Victoria suggest FBA typically clump together, making high infestations easy to spot. Warm temperatures have increased their numbers. Hosts for FBA include:

- faba beans

- broad beans

- vetch.

The NSW Department of Primary Industries suggests that FBA prefers faba bean and vetches, followed by common pea and lentils. Lucerne, sub clover and legume weeds support limited reproduction of FBA, acting as alternative hosts all year round.

What FBA looks like

FBA are large and can coexist on leguminous plants with the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum), blue green aphid (A. kondoi) and cowpea aphid (Aphis craccivora) but are easily identified:

- up to 2.5 to 3 millimetres in length

- red eyes

- dark green spindle-shaped body with long legs and antennae

- black head, pro-thorax, antennae, leg, siphunculi ('exhaust pipes') and cauda ('tail')

- large tubercles (structure at the base of antennae) that face outwards when viewed from above

- slightly swollen siphunculi.

Using a little hand lens the red eyes are easily seen and are a clear distinguishing characteristic.

The latest information for growers and advisors on the activity and management of pests in all broadacre crops during the winter growing season.