PestFacts September 2021

Pests to look out for in emerging crops

In the past few weeks, armyworm have been reported at many locations across South Australia, including:

- on wheat and barley at Balakava

- on wheat amongst lentils at Halbury

- in a wheat trial at Tarlee

- 5–20mm long caterpillars on cereals at Tumby Bay

- on wheat at Cleve

- 3 leaf to early tillering cereals at Manoora

- on cereals in the Mid North (exact location unspecified).

Source of reports: Chris Pearce (Nutrien), Michael Nash (supported by SANTFA, through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.), Cherylynn Dreckow (Elders), Lauren Philps, Chris Davey (YP Ag).

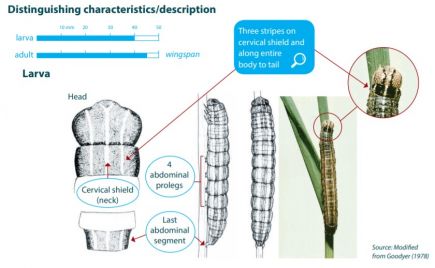

How to identify armyworms

Armyworms are identifiable by 3 parallel white stripes along their body, most prominently seen on the cervical shield (“neck” or collar). Older caterpillars crawl around at night and may move up and down grass and cereal plants regularly. They spend the day curled up at the base of the plant under clods of soil or in the plant crown.

3 species of armyworm are common in southern Australia. Other regions have different species.

Armyworm species found in southern Australia

- Southern and inland armyworms (Persectania species) are more typically found during autumn and winter, but their activity can sometimes spread into spring.

- Common armyworm (Leucania convecta) can potentially be seen year-round, but particularly in spring.

Armyworm caterpillars can be confused with:

- native budworm ( has more prominent body hairs than armyworm caterpillars)

- cutworms (cutworms have indistinct or no stripes absent or indistinct),

- other grass feeding noctuids such as herringbone caterpillars (herringbone caterpillar have herringbone-like markings on the stripes down the body).

The exotic fall armyworm (FAW, Spodoptera frugiperda) looks similar to other native armyworms and has the typical 3 stripes. For more information on identifying FAW, see PestFacts Issue 1 2020 and The Beatsheets’ FAW Identification webpage. It has not been detected in SA and is a reportable pest. If you suspect a caterpillar is FAW, please contact the Emergency Plant Pest hotline 1800 084 881 or submit an online plant pest report form.

As a PestFacts SA subscriber, you can receive free identifications of both samples and photographs. You can also check out our tips for smartphone insect photography.

How to report

PestFacts SA always wants to know what pests you are finding in your crops and pastures, whether it is the ‘usual’ pests, beneficial or unknown. Reports of not seeing anything are valuable too! Please send your reports or identification requests via the PestFacts Map online report form.

Alternatively, please contact:

Rebecca Hamdorf

Phone: 0429 547 413

Email: rebecca.hamdorf@sa.gov.au

Maarten van Helden

Phone: 0481 544 429

Email: maarten.vanhelden@sa.gov.au

Spring brings friends alongside foes

Canola crops are flowering! During this stage, there can sometimes be large populations of cabbage aphids (Brevicoryne brassicae) developing on the flowering stems. Now is the time to monitor and consider management.

Cabbage aphid monitoring and threshold guidelines

Monitoring for canola aphids should begin in crop edges as these are typically infested first. Inspect at least 20 plants at 5 sampling points over the paddock. Cabbage aphid colonies have a characteristic blue-grey appearance and are normally covered in a thick, whitish powder, whereas turnip aphid (Lipaphis pseudobrasssicae) colonies have a lighter covering of wax and appear green in colour.

Threshold guidelines for cabbage aphid and turnip aphid: consider control where > 20% of plants are infested, or > 10% of plants with > 25 mm of stem infested. When determining economic thresholds for aphids it is critical to consider several other factors before making a decision including:

- current growing conditions

- moisture availability

- populations of natural enemies or beneficials.

Beneficial pest throughout south eastern Australian

With spring comes a boom in natural enemies on the hunt for aphids and other pests. Low populations of other canola aphid species (green peach aphid and turnip aphid) might have helped the build-up of beneficial populations in the crop.

Here are a few of these beneficial groups found throughout south eastern Australia:

Parasitic wasps

Several species of parasitic wasps lay their eggs into aphids or caterpillars. The developing wasp larva either feed inside the host or hang on to the outside of the host while feeding. Aphid ‘mummies’ – bronze-coloured, bloated or enlarged aphids – indicate the activity of aphid parasitic wasps and a new wasp is about to emerge. Even with little mummies visible, parasitism can be quite high, simply because the mummy is only the very last stage of wasp development.

Aphid parasitic wasps are specialists in their trade, usually attacking just a single pest species. They can only live where and when their hosts occur.

Caterpillars parasitized by parasitic wasps often have a large number of larvae crawling out and pupate around the dead caterpillar.

Ladybird beetles

Found in all crops, both ladybird larvae and adults are voracious predators of aphids. They also prey on leafhoppers, thrips, mites, moth eggs and small caterpillars.

Ladybird beetles undergo a significant transformation as they mature. As larvae, they have grey or black elongated bodies with orange markings and may be covered in spines or white fluffy wax material. As adults, they are round to oval-shaped, with black spots on red, orange or yellow shells. Unfortunately, ladybeetles often do not multiply quickly enough to control outbreaks.

Hoverflies

Hoverfly larvae (Family: Syrphidae) attack a range of soft-bodied insects but prefer aphids. They are common in flowering crops, such as canola, pasture paddocks, and on some roadside flowering weeds.

Hoverflies are most noticeable in the adult fly form when they have dark-coloured flattened bodies with black and yellow markings. But it is the larval ‘grub’ stage (a greenish or cream maggot) that is predatory. As larvae, they are often mistaken for pest caterpillars such as diamondback moth but lack the typical head capsule of caterpillars.

Lacewings (brown and green)

Lacewings are voracious predators and will try to eat almost any insect standing in their path, including aphids, thrips, mites, caterpillars and moth eggs. Brown lacewings adults and larvae are both predatory, while only green lacewing larvae are predatory – the adults becoming nectar and pollen feeders following pupation. After sucking the internal contents of their prey, lacewing larvae impale their victim’s exoskeletons on their backs. Brown lacewing larvae can eat between 100–200 aphids during their lifetime.

Larvae lack wings and have protruding sickle-shaped mouthparts and a body that is long and varies from thin to stout-like in shape. As adults, they have prominent eyes and long antennae, with large, clear wings with numerous veins giving a lacy appearance.

Earwigs

You might consider European earwigs as a pest as they can nibble off plants and kill seedlings – they are also good predators of aphids! Therefore, in later growth stages they often are a beneficial insect. You often will find earwigs in rolled leaves of cereal where they are hiding during the day, consuming aphids during nocturnal feeding.

The native earwig species are not known to damage seedlings and are a predator but, unfortunately, they rarely show high populations in crops.

More information

Now's the time to stay ahead of redlegged earth mite

Redlegged earth mite (RLEM, Halotydeus destructor) is a common resident pest. These pests are active from autumn to late spring, when the third generation of mites produce over-summering eggs that will hatch in the following autumn. Populations can be limited using the TimeRite® strategy, if necessary.

How do I know my risk?

To help you decide if a TimeRite® application is beneficial, the GRDC Redlegged earth mite best management practice guide can be used to evaluate the risk of RLEM on your property based on:

- previous crops

- observation of mites this month

- sensitivity of the future crops.

Or you can use the interactive risk calculator developed by Cesar Australia.

Only spray if necessary

RLEM is becoming increasingly resistant to many pesticides.

It is important that you only spray if:

- RLEM numbers are currently high

- a sensitive crop is being sown next year.

Ensure you correctly identify the mites you find because the TimeRite® strategy only works on RLEM. The GRDC Crop Mites Back Pocket Guide is a useful tool to help distinguish between these mites.

As a PestFacts SA subscriber, you can always send photos (using GoMicro or a similar macro phone lens works best) and specimens to us by contacting:

Rebecca Hamdorf

Phone: 0429 547 413

Email: rebecca.hamdorf@sa.gov.au

Maarten van Helden

Phone: 0481 544 429

Email: maarten.vanhelden@sa.gov.au