PestFacts April 2021

RWA: can we predict a risk for the coming season?

Increasing our knowledge of Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) dynamics through research funded by GRDC and SAGIT investments allows to have a better understanding of the risk factors for autumn sown wheat and barley crops. One obvious major population bottleneck for RWA is summer survival on the ‘green bridge’. You might think that more summer rain would increase the risk for RWA in the autumn sowing, but it is certainly not that simple.

Possible ‘green bridge’ hosts of RWA

The main wild host plants for RWA are barley grass (Hordeum glaucum and H. leporinum) and brome grasses (Bromus spp. including prairie-grass), with several other species (wild oat, Phalaris spp., ryegrass, volunteer cereals) occasionally showing some lower population numbers. However, these grass species are not summer active unless they are maintained by available water, rainfall or irrigation. Barley grass does not germinate in summer as the seeds are dormant. Therefore, most of these grass hosts are in fact not available for RWA in summer.

Some native grass species, such as bottle-washers (Enneapogon sp.), a dominant species on many roadsides in dryland areas, are actively growing in summer (sometimes helped by grazing kangaroos) and we showed that small numbers of RWA can persist on these.

Possible green bridge scenarios

Combining this data with observations from the field we hypothesise the following green bridge scenario:

In a typical dry Australian summer, the amount of suitable grasses (both suitable species and total amount of grasses) for RWA decrease during the November/December/January period. This results in a very low widespread resident population of RWA on very few native grasses. If rainfall occurs during this period prairie grass might persist and it might cause some germination of volunteer cereals, but it will not result in a high build-up of RWA.

If significant rainfall occurs later from February onwards, the amount of grasses (including barley grass and brome grasses) germinating will be more significant and RWA can start to build up on these. However, it will take a few months for the populations to build up, so additional follow up rainfall is needed to allow this. Later rainfall (March and April) without early rainfall would also cause grasses to germinate but is likely too late to allow RWA populations to build up before sowing.

The challenges of migrating for an aphid

Whatever level of RWA population develops on available grasses, before there is a risk for your crop these aphids will still need to migrate to the paddock. Presuming you haven’t already eliminated the grass weeds in the paddock a few weeks before sowing as good agricultural practice requires.

RWA will only migrate from a host plant if the plant is maturing and senescing. For small, soft-bodied insects like aphids, migration is a very high risk as the probability of flying, or rather ‘being gone with the wind’ to a suitable host is very low and the risk of drying out or being eaten during migration is high. So RWA will only develop wings if the plant they are feeding on is no longer suitable, and only then they will launch their Kamikaze attempt to find a new plant. Over 99% of aphids will probably die during migration (Ward et al 1998).

So, even if a grass contains plenty of RWA, as long as it is healthy, the aphids will not migrate. We have observed that on several occasions: with barley grasses full of RWA but no RWA in the cereals of the neighbouring paddock.

RWA will only migrate if the grasses on which RWA is developing are maturing or slowly dying from drought in a desperate attempt to find new resources. That’s why we expect that a summer rain in February is a much higher risk factor than earlier rains (no barley grass germinating) or later rains (barley grass will not be maturing before June/July). This is in line with last years’ higher RWA infestations in the Mid-North and northern EP after a very early break at the start of February.

What’s the early season risk for RWA?

Over the last summer we have had several early rainfall events, but now it is very dry again in most areas. There are some reports of RWA on volunteer cereals, but there does not seem to be a big early flush of barley grasses or brome grasses on which RWA could be building up. When running the existing RWA CLIMEX model (Avila et al 2019) on a week by week basis using BOM data for the whole of Australia, we can observe that weather and soil conditions are favourable in some areas and some weeks for the aphids that would be there. However, for RWA to build up such favourable conditions need to be sustained for long enough (at least two months) to have RWA populations build up.

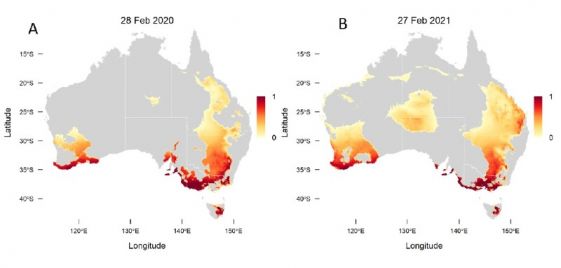

As an illustration, Fig. 1 shows the conditions at the end of February in 2020 and 2021.

When looking at South Australia only, this model shows that in 2020 the conditions for RWA were favourable in the Port Augusta - northern Eyre Peninsula area, and this was later confirmed by reports of RWA in cereal crops in the Mid-North. This year the RWA CLIMEX model predicts unfavourable conditions in that area, so we presume there will be no high RWA pressure in 2021.

Interestingly the southern tip of EP is showing good conditions for RWA this autumn, it might be that there will be some RWA, we are looking forward to hearing from agronomists and growers in the area.

It’s only a model…

We are showing this as an illustration of what could be done with modelling, but we are far from having a validated model so be critical (as you should be on every model) and do not base important decisions on such model ‘predictions’ alone. Always validate predictions with monitoring. Overall, the end of summer has been quite dry in SA, we are expecting little issues with RWA resulting from the green bridge.

Even if the model shows a dark red in your area it does not mean there will be RWA in your crop. As this model is applied to all of Australia it even calculates a risk in areas where RWA has not been recorded. For Southern Victoria and Tasmania where RWA is likely to be able to survive summers easily (not too hot, not too dry), problems in crops have not been recorded, probably because there is no reason for the aphids to migrate in Autumn as their host plants are still good.

Please keep reporting RWA to:

- Maarten van Helden: 0481 544 429 or maarten.vanhelden@sa.gov.au

- Lizzy Lowe (Cesar Australia, PestFacts South Eastern): llowe@cesaraustralia.com

You can use the RWA economic threshold calculator to determine if an insecticide would be economic or not.

Written by Maarten van Helden, Kym Perry

References

Avila, G.A., Davidson, M., van Helden, M. and Fagan, L. 2019. The potential distribution of the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia): an updated distribution model including irrigation improves model fit for predicting potential spread. Bull Ent Res 2019 109:90–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485318000226 PMID: 29665868.

Ward, S. A., Leather, S. R., Pickup, J. and Harrington, R. 1998. Mortality during dispersal and the cost of host-specificity in parasites: how many aphids find hosts? Journal of Animal Ecology. 67 (5), pp. 763-773. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.1998.00238.x

Slug baiting for integrated control

With seeding approaching, now is the time to monitor paddocks for slug activity. Slug baiting in infested areas should occur at or immediately after sowing, before seedling emergence, to protect seeds and seedlings from actively feeding slugs.

The seasonal risk from slugs is elevated in parts of SA in early 2021 following generally favourable conditions during spring and summer 2020/2021. Above average rainfall in September† (mainly Kangaroo Island and Lower South East regions) and October† (most of SA’s cropping zone, to a lesser extent the South East region) may have prolonged slug reproduction last spring. A generally mild summer with below average temperatures across SA, especially in December† and February†, potentially aided slug survival.

Slug biology and damage

The black-keeled slug, Milax gagates, and the grey field slug, Deroceras reticulatum, are the two major slug pests of all crop and pasture types in southern Australia. Canola is especially susceptible to damage. Other species that may be present include brown field slug (most likely Deroceras invadens or D. laeve; some taxonomic uncertainty exists) and striped slug, Lehmannia nyctelia.

Slugs are generally more problematic in higher rainfall climates (> 500mm) and seasons, and in paddocks or paddock area with heavy soils that retain moisture or crack. Slugs attack crops at all stages but cause most damage to seedlings. Grey field slugs feed mostly on the soil surface, attacking plants at ground level and consuming cotyledons, leaves and stems, sometimes severing seedlings. Black-keeled slugs feed similarly at the soil surface but also burrow below ground to attack germinating seeds.

Slugs are mostly inactive during summer. The black-keeled slug burrows to depths of 20 cm or more to survive the heat, whereas the grey field slug seeks refuge under rocks, logs or summer weeds and debris, or by moving into cracks in the soil. Soil-penetrating rainfall and cooler temperatures increase slug activity surface on the soil surface in autumn and winter.

Monitoring and baiting slugs

Monitor slug activity using surface refuges or bait lines. Focus monitoring in areas with a history of slug problems and/or moisture-retaining soils.

Silver slug mats are more attractive to slugs than tiles for refuge-based monitoring of slugs (more than 4-fold more slugs captured), shown by recent research by SARDI and DPIRD [1]. Place refuges along several rows (i.e. transects) in representative paddock areas, with pellets underneath each refuge, and check for slugs after a few days. Slug numbers can vary greatly between transects.

Bait lines are a useful alternative to refuges for slug monitoring. Place a line of pellets (e.g. 100m in length) along a seeding furrow and check for dead slugs after a few days. Do this in several furrows. Bait lines are easy to apply and monitor but may need re-application after 2-3 weeks or when pellets break down.

The presence of dead slugs under refuges or in bait lines indicates slugs are actively feeding, and bait should be applied. After application, monitor and re-apply as necessary. For information on bait products, refer to the SARDI snail and slug baiting guidelines.

Integrated control

Baiting slugs at sowing is part of year-round integrated slug management, together with cultural controls. Slug populations can be reduced by fine tillage followed by rolling. Slugs can be managed in no-till systems by well-timed baiting at sowing in combination with agronomic practices to achieve rapid crop establishment. These include early sowing before slugs are active, use of hybrid rather than open-pollinated seed varieties, rolling to compact the seed bed and restrict slug movement, and weed management. Further slug management advice is available in a recent GRDC Paddock Practices article.

References and further reading

† Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology, climate data maps for South Australia, monthly anomalies for rainfall and mean maximum temperature).

[1] Perry KD, Brodie H, Fechner N, Baker GJ, Nash MA, Micic S, Muirhead K (2020b). Biology and management of snails and slugs in grains crops. Final report for GRDC (DAS00160). South Australian Research and Development Institute, December 2020.

SARDI snail and slug baiting guidelines ().

PestNote – Black-keeled slug ()

GRDC Paddock Practices - Be on alert for slugs in the high rainfall zone

Fall armyworm movement update

Since its detection in Northern Australia in early 2020 fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) has migrated to other regions. FAW is a strong flier and is believed to have covered most of this range through natural dispersal.

FAW moths and larvae have been found in all NSW key summer cropping regions, and now has been detected in northern Victoria. The first sighting occurred in December 2020, and Cesar Australia’s PestFacts south-eastern FAW pilot-trapping network has caught it in their traps.

There have been no detections of FAW in South Australia yet.

What’s the current risk for SA?

As discussed in PestFacts SA Issue 1 2020 climate suitability for FAW is low, and it is not expected to establish. Recent predictive modelling work led by Dr James Maino (Cesar Australia) suggests that from April onwards parts of SA becomes unfavourable for FAW population growth and by May all cropping regions will be. Milder than usual conditions in spring and autumn may extend the period of suitability.

Whilst FAW has a wide potential host range (>350 known plant hosts), the crops of main concern are corn and rice. Summer cropping, particularly of corn, is at highest risk of fall armyworm damage. As the weather cools we expect that the risk of incursion decreases.

Reporting fall armyworm

If you suspect FAW is present in your region, report it immediately to the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. The hotline will connect you to the responsible authority in your state or territory. Reporting the presence of FAW will assist in the response effort.

Unusual caterpillars can be reported to PestFacts SA through the online PestFacts Map reporter, or by contacting the following for identification:

- Rebecca Hamdorf: Rebecca.Hamdorf@sa.gov.au or 0429 547 413

- Maarten van Helden: Maarten.vanHelden@sa.gov.au or 0481 544 429

Further information on fall armyworm

- GRDC Grains Research Update, online – Fall armyworm

- Fall armyworm: what threat does it pose, and what tools do we have to manage it?

- GRDC fall armyworm portal

- The Beatsheet Blog: Fall armyworm

- Regional and seasonal activity predictions for fall armyworm in Australia – Maino et al. 2021

- Fall Armyworm Continuity Plan for the Australian Grains Industry

Heliotrope moth – not a problem

Over the last month reports of large numbers of adult Heliotrope moths (Utetheisa pulchelloides) have been reported in stubble with potato weed (Heliotrope sp.) on the Eyre Peninsula. Heliotrope moth caterpillars have also been reported feeding on potato weed.

Caterpillars have only been reported feeding on plants from the comfrey family (Boraginaeceae) including potato weed and salvation jane (Echium plantagineum). They are not known to feed on crops, and due to feeding on weeds are considered a beneficial.

How to identify Heliotrope moth

Caterpillars are black with orange spots, a broad broken cream line along the back and a narrow-broken cream lines along each side. They have quite long, grey hairs in sparse clusters along its length, and can grow up to 30mm.

In flight the moths appear white or very light grey, but when at rest a distinctive pattern of red and black spots on the white forewings can be seen. The hind wings are white with an irregular black margin. The wingspan can be up to 30mm.

Source of reports: Mark Habner, Kevin Dart, Josh Hollitt.