The Callaghan era 1949–c1959

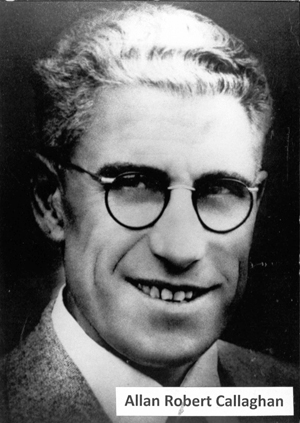

Allan Callaghan, was born near Bathurst, NSW, and completed his B.Ag.Sc degree at the University of Sydney in 1924.

Allan Robert Callaghan

Social and economic context

During the decade in which A.R. Callaghan was Director of the SA Department of Agriculture it will be helpful to summarise the rapid changes that were occurring in Australia’s economy, industries and society. Following is a brief summary of this changing environment.

Australia’s economy was severely hit by the Great Depression of the late 1920s – early 1930s, especially the rural industries and, in particular, those which had a major dependency on export markets – wheat, wool, dairy produce, meat, eggs, and some fruits.

The first signs of recovery were beginning to appear by 1939 when World War 2 broke out. Over the next six years, agricultural production was adversely affected by shortages of many key inputs, including fuels, vehicle tyres, fencing and building materials. Although farming was treated as a protected occupation, there were labour shortages.

The end of WW2 in 1945 heralded a more optimistic outlook but this took time to translate into physical changes. For some years after WW2, availability of many materials was affected by serious industrial disputation on the waterfront. As war-torn areas of the world gradually recovered, especially Britain and Europe, markets and prices for agricultural commodities improved. These were given a major boost by the Korean War (1950–53), which increased demand for Australian wool. Rationing and supply controls for inputs were eased and then abandoned. The economic outlook of Australia as a whole was much uplifted.

Australian made Holden cars appeared in 1949, and Australian-made cigarettes were easier to get. Air travel became faster, with more flights to more places (although South Australia’s public servants travelling to Melbourne on official business were still required to take the over-night state government owned train service). Optimism was general and agricultural industries were expanding rapidly.

The use of trace elements enabled large areas of medium to high rainfall native vegetation to be developed as productive pasture land. Much of the new land was settled by returned servicemen. Generous income tax concessions also enabled city-based professionals and businessmen to offset the costs of land development. Not only were high wool prices making sheep-raising highly profitable in the permanent pasture areas but they boosted the development of mixed cereal-sheep farming in the medium rainfall areas with profound beneficial effects on farming areas of the Eyre Peninsula, lower and mid-north and much of the Murray Mallee.

In the later stages of World War 2 the Commonwealth Government had set up a Rural Reconstruction Commission under the chairmanship of Professor (later Sir) Samuel Wadham, Head of the University of Melbourne’s Agriculture School. The Commission produced ten reports for the planned post-war recovery of Australia’s agriculture industries.

The transformation of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) into a high-powered statutory corporation (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation – CSIRO) in 1949, under the dynamic leadership of its first Chairman, Sir Ian Clunies Ross, led to a huge and immediate development in agricultural (as well as secondary industry) research activity. Apart from the intrinsic value of its programs, the associated, widespread publicity greatly increased general awareness throughout Australia of the contributions that could be expected from science.

The Commonwealth and State Governments, through the Australian Agricultural Council, were confident enough of the future of farming in 1952 to set increased production aims for the nation’s major cropping and livestock industries.

Organised marketing schemes gave the promise of stable and worthwhile prices for much of the country’s rural produce. The rural industries were clearly recognised in those days as by far the biggest earner of export income, and Australia was thought of as “riding on the sheep’s back”.

The post-war era brought an upsurge in farm mechanisation. Tractors of various sizes became more readily available, with power take-offs and three point linkages, enabling the use of a wide range of new implements. This included more efficient crop harvesters, hay balers, post hole diggers and buck-rakes. The days of the horse to provide power on farms were over and even its use for stock mustering eventually gave way to the motor cycle. The reticulation of electricity and water to rural areas brought amenity and a new source of power for many farm operations.

All of this engendered a strong sense of optimism and confidence in the future, creating a social, economic and indeed political atmosphere in which Callaghan’s vision and dynamic leadership skills were able to have full effect. It was a very exciting time.

Allan Callaghan’s career pre Department of Agriculture

Winning a Rhodes Scholarship, he went to Oxford where he gained the degrees of Bachelor of Science and Doctor of Philosophy. On return to Australia he took up an appointment in the N.S.W. Department of Agriculture, working as a plant breeder at Wagga and Temora.

In 1932, at the age of 28, he was appointed Principal of Roseworthy Agricultural College. Over the next 17 years he revitalised the college, restoring student morale, introducing new diploma courses in oenology and dairying, and embarking on vigorous plant breeding programs, cropping research and demonstration projects for mixed farming systems and fat lamb production.

During World War 2 he was seconded as Assistant Director for Rural Industries in the Commonwealth Department for War Organisation of Industry. Despite the frustrations that came with this appointment, he made many valuable contacts with men who were to become the leaders of Australia’s government agricultural agencies in the post-war period.

He returned to South Australia in 1942 and resumed his role as Chairman of the Crown Lands Development Committee. As the end of the war approached, this body became the Land Development Executive, given the task of identifying land in higher rainfall areas considered suitable for clearing, sowing to improved pastures and fencing, ready for occupancy by the large number of War Service Land Settlers expected after the war. In recognition of his sterling work in this task, he was awarded the C.M.G. in 1945.

Director of Agriculture

Highly regarded by Public Service Commissioner L.J. Hunkin (who had put his faith in Callaghan by appointing him as Principal of Roseworthy at what most people thought was a ridiculously young age) and by members of the government, Callaghan followed Spafford as Director of Agriculture, being appointed on 30 May 1949. This appointment led to the most dynamic decade in the structural development of the SA Department of Agriculture.

Changes to staffing policy

Callaghan believed that the time had come to make significant changes in staffing and commenced a restructuring process. He sought to recruit well-trained, younger men with fresh ideas.

One of the earliest examples of this came when long-serving Chief Dairy Instructor H.B.D. Barlow retired. The vacancy was widely advertised and a young Graham Itzerott, with a master’s degree from the University of Melbourne and good experience with the Victorian dairy industry, was selected for the post.

In those days, existing State public servants could appeal against proposed “outside” appointments and Barlow’s most senior colleague exercised this right. The appellant, in support of his case, told the Appeal Board, in some detail, of his long and varied service to South Australia’s dairy farmers. The Board asked Callaghan to comment on this; he responded that everything the appellant had said was true and that he was a dedicated and competent officer. “However”, said Callaghan, “I did not hear a single word about the future of our dairy industry”. Needless to say, the appeal was dismissed; Itzerott was appointed and went on to provide great leadership in the development and management of the department’s dairy industry services for the next 30 years.

With the retirement of L.J. Cook (Chief Agricultural Adviser) imminent, Callaghan saw the need to strengthen the department’s staff resources across the field of agronomic research. Cook had given long service and was highly regarded for his early recognition of the basics of improved pasture management and for the development of a wide range of pasture and cereal applied research and demonstration projects on departmental experiment stations and on selected farmers’ and graziers’ properties.

The post of Experimentalist was re-designated Chief Agricultural Adviser and Cook took over the role which had been filled by Spafford’s de facto deputy, Colin Scott, recently retired. Callaghan secured new positions, under Cook, of Senior Agronomist, Senior Research Officer (Agronomy) and Research Officer (Agronomy). In these positions outstanding agricultural science graduates from the staff or the post-graduate group of the Agronomy Department, Waite Institute, were appointed – A.J.K. Walker, N.S. Tiver and E.D. Carter, respectively.

In 1953, Callaghan merged the livestock husbandry, (other than dairy cattle) pigs, poultry, sheep and beef cattle, sections into a Livestock Branch. The head of this new branch, Chief Adviser in Animal Husbandry, was a recruit, Marshall R. Irving, a veterinary surgeon and Hawkesbury Agricultural diploma holder. Irving had wide experience working with the livestock industries of Queensland and the Northern Territory, and was supported by C.T. McKenna, an existing departmental veterinary officer appointed to the new post of Senior Research Officer, Animal Husbandry.

The Dairy Branch was to remain a separate entity for many years, in recognition of the close ties between dairy herd management and the processing of dairy produce, often at local levels

Another first for the department was the creation of the post of Scientific Liaison Officer. This new officer provided the Director with a resource dedicated to supporting him in a vast array of technical, policy and administrative tasks – virtually a Technical Secretary.

H.P.C. Trumble, an agricultural science graduate, was the first Scientific Liaison Officer appointee. He was kept busy supporting Callaghan’s boundless energy in writing reports and other publications, public speaking, organisation of departmental committee work, and, in particular, preparation for and follow up of the Department’s increasingly important work as part of the Standing Committee / Australian Agricultural Council system.

Strengthening research and extension

Callaghan had very strong views about the framework within which the State’s services to rural industries should be delivered. There was no argument about the sole responsibility of the Department of Agriculture for regulatory services. These responsibilities were founded upon Acts of Parliament. Furthermore, the Department was generally recognised as the principal deliverer of agricultural advice to primary producers.

Relationship with the Waite Institute

With research, the situation was less clear. Callaghan led the 1949 initiative of the Minister of Agriculture to review the relationship between the Waite Institute and the Department of Agriculture. This created a new agreement between the SA Government and The University of Adelaide, which better defined research and advisory responsibilities of the Waite Institute and Department of Agriculture. It set out for the first time the concepts of basic research (being delivered by the Waite Institute and CSIRO), and applied research (aimed at solving defined field problems), and closely linking these to advisory programs for farmers (i.e. extension work being delivered by the Department).

This agreement immediately brought a change of emphasis at the Waite, especially in the Agronomy Department which for two decades had developed valuable applied research programs (see Creation and Development of the Waite Institute – Perkins Era 1914-1936).

Waite Institute staff members were often sought as speakers at Agricultural Bureau meetings and for the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s rural radio programs and as contributors of articles on farm problems by the rural press. The applied research programs of the Entomology and Plant Pathology Departments at the Waite Institute were less affected in the short term because of the existing agreement between the SA Government and the University, enshrined in the Agricultural Education Act 1927. In any event, the Department of Agriculture at the time did not have the expertise to become significantly involved in these areas.

Having started with strengthening the Department’s agronomic research resources and with the Horticulture Branch already staffed with a number of research officers under the leadership of Senior Horticultural Research Officer, Harry Kemp, Callaghan next turned to developing other applied research units in soils and animal husbandry, and to carry out work on insect pest and plant disease problems. Animal disease research remained in the hands of the Veterinary Science Division of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science.

Callaghan’s vigorous pursuit of more resources to enable the fulfilment of his vision for a well-rounded, applied research capability, to meet the major needs of the State’s rural economy, led to some resistance from the government. Premier Tom Playford famously once asked Callaghan “What are you trying to do, Dr Callaghan? Create another Waite Institute?” Although the ear-marked government grant to the Waite to recognise its provision of services concerning insect pests, plant diseases and plant identification, ceased in 1952, Playford’s question may well have been triggered by Callaghan’s attempt to enter the fields of pest and disease research.

The advent of external funding

Callaghan’s hand was greatly strengthened by the development and rapid growth of funding from sources outside the State Treasury to pay for major research and extension programs. This development began in 1948–49 with the introduction of the Commonwealth Dairy Industry Efficiency (later renamed Extension) Grant.

This was funded by the then Commonwealth Department of Commerce and Agriculture. It aimed to bolster the services of State Departments of Agriculture and dairy industry productivity by improving dairy cow management in the paddock and the milking shed. In its first year the grant provided the Department with three new Field Officers and funded 48 applied research and demonstration projects on dairy farms. This fund also financed automation of herd recording data by the provision of Powers–Samas Punch Card data processing equipment, the fore-runner of modern computers.

For several years there had been a substantial program of funding for wool research with monies raised by a Commonwealth levy on wool-growers, supplemented by funds from its general revenue. The Australian Meat Board had also funded beef cattle growth and fattening studies at three centres in South Australia.

In the mid 1950s, industry levies were further developed. Levies gathered from agricultural industries were matched with Commonwealth contributions to create and manage substantial funds for research and extension. As these levies were an excise, they required Commonwealth legislation to be valid. Over a period, wheat, meat, dairy, tobacco and horticulture joined the wool industry in major funding arrangements throughout Australia, aimed at the research support for those industries.

The wheat industry schemeprovided a notable exception to the general pattern in that, while the Comonwealth contribution was managed by a national Wheat Industry Research Council, the funds contributed by each state's wheat growers were in the hands of a State Wheat Industry Research Committee with majority grower representation.

Callaghan played a pivotal role in shaping these national levy funds and accessing resources from them to provide services to SA’s agricultural industries. This included the following:

The Barley Improvement Trust Fund

Of special interest to South Australia and Victoria was the levy scheme to aid the barley industry. It was deemed inappropriate to introduce the necessary Commonwealth Act to impose a research levy on all barley growers and Callaghan, with the support of the Australian malting and brewing industries and the Australian Barley Board (on behalf of South Australian and Victorian growers) brokered a voluntary scheme whereby these three elements of the barley industry contributed funds. The Commonwealth Minister for Primary Industry was persuaded to subsidise expenditure on approved projects from these funds, pound for pound, to bring the arrangement into de facto parity with the other legislatively-based levy programs.

The structure to manage this scheme, under the aegis of the South Australian Minister of Agriculture, comprised:

- A Barley Improvement Trust Fund, within the State Treasury, which received the industry and Commonwealth contributions and from which the research grants approved by the Minister were paid.

- A Barley Improvement Advisory Committee, chaired by Callaghan (who also represented the South Australian government interest) and made up of representatives of each of three industry groups contributing funds, the governments of the Commonwealth and Victoria, together with the Director of the Waite Institute.

- A Barley Improvement Technical Committee, chaired by Chief Agronomist A.J.K. Walker, which included representatives of the two Departments of Agriculture (Victoria and South Australia) involved in the research programs, the Departments of Agronomy and Plant Physiology at the Waite Institute, and a senior technical expert from each of the brewing and the malting industries.

The Technical Committee would evaluate the submissions each year for barley improvement projects and recommend an annual program to the Advisory Committee for consideration and recommendation to the Minister for final approval. The S.A. Department of Agriculture provided accounting services to the scheme and the department’s Scientific Liaison Officer was secretary to both Committees.

Two initial appointments were in the department’s Agronomy Branch – a Barley Agronomist (Peter Barrow) and a project officer to supervise the expanded program of field work (Glynn Webber).

The Commonwealth Extension Services Grant

The Commonwealth Extension Services Grant (CESG) was introduced in 1952–53 with no specific industry ties attached. These CESG grants enabled supplementation of the Department’s extension and applied research resources by creating supporting staff positions for technical illustrators, publicity officers and provision of modern audio-visual equipment. These greatly improved the effectiveness of the department’s advisory and information programs.

In those days there were still many out-lying rural communities without mains electricity. The purchase of a specially equipped vehicle with 240 volt generator enabled films and slide projection to be used in support of technical talks to every Agricultural Bureau branch in the State.

By the end of Callaghan’s time in 1959, funds for research and extension projects from all sources outside the State Treasury had grown to 12% of the Department’s total expenditure. This was very significant because the whole of the costs of the Department’s management, administrative and regulatory (other than as agent for the Commonwealth) services were provided from the State funds.

Formalising research centre management

In the latter years of Callaghan’s directorship, he introduced the Department’s first research management systems. This was through establishment of a Research Centres Policy Committee. This committee comprised the Director of Agriculture (Chairman), the chiefs of the three divisions, the Secretary (i.e. Chief Administrative Officer), with the Scientific Liaison Officer as committee secretary.

Every year it would have a series of meetings concerning the existing and proposed programs for each of the ten research centres. The Officer-In-Charge of the relevant centre and his Head Office counterpart would join the committee to consider the proposed annual program of research projects, along with any resource requests for additional staff, structural development and capital items. The committee’s decision was then reflected in the appropriate parts of the Department’s budget for the coming year.

At the time, the ten research centres were located at Berri, Blackwood and Nuriootpa (all administered by the Horticulture Branch), Wanbi (Soil Conservation), Parafield Poultry (Animal Husbandry), Parafield Plant Introduction (Agronomy) and Kybybolite, Minnipa, Struan and Turretfield (for which Head Office interest was shared between Agronomy and Animal Husbandry).

This process brought for the first time a formal, across the board focus on the programs and budgetary requirements of applied research activities.

Supportive rural organisations

Allan Callaghan clearly recognised the enormous value of the Agricultural Bureau system in South Australia. In 1950 he said “The Agricultural Bureau may be described as the keystone of the Department’s extension and advisory work since it is the principal channel through which the Department distributes the knowledge at its disposal. For more than 50 years the bureau system had provided organised centres throughout the State, and enabled a relatively small technical staff to accomplish a remarkably large amount of extension work.”

At that time, the bureau branches had a total of about 11,000 members comprising nearly 40% of the State’s farmers, graziers and orchardists. A year later, Callaghan was to add: “Since its inception the Agricultural Bureau has remained clear of all political influence. It has succeeded because it has remained a purely mutual, educational organisation, untarnished by political controversies.”

Ever on the lookout for an opportunity to challenge and inject fresh ideas, in 1952 Callaghan secured the appointment of Dorothy Marshall, O.B.E., as Women’s Agricultural Bureau Organiser. Her experience in assisting with refugee problems in post-war Europe added to her considerable leadership and organisational skills. Miss Marshall brought a new dimension and wider horizons to the programs and activities of the Women’s Branches.

The previous year, Callaghan had initiated the formation of young farmers’ clubs in South Australia. The new organisation was called the Rural Youth Movement. It was not conceived as an organisation dealing purely with on-farm matters. The Rural Youth Movement was also to provide appropriate social activities for young country people and to create an awareness of social, economic and cultural issues affecting rural communities and their interactions with their city counterparts. Callaghan always stressed that the Rural Youth Movement should have a significant presence in metropolitan Adelaide.

A Rural Youth Council was established in 1951, with representatives of the Education Department, the banking sector and the rural media joining Department of Agriculture staff. This council planned the launching of the Rural Youth Movement with a network of branches throughout the State. An experienced agricultural extension officer with a well-developed interest in youth activities (Peter Angove) was appointed as General Supervisor. The first branches were formed in 1951–52, their numbers growing to 87 five years later, with about 3,000 members. This structure provided solid development at the club level and the support of local adult advisory committees and guidance of Rural Youth Advisors in the Department.

In 1955–56, a State Committee of Rural Youth, comprising representatives of groups of branches, was formed, giving the Movement a measure of self-government, and in 1959 the age limit for membership was raised to 25, recognising the need to maintain the involvement of young adults.

A major Department of Agriculture reorganisation

In 1954–55, Callaghan secured Public Service Board approval for a major restructuring of the Department and, by the following year this was in place.

It provided for the six established technical service-delivery branches to be grouped into two divisions, each led by a Divisional Chief. The Division of Plant Industry under A.G. Strickland comprised the Agronomy, Horticulture and Soil Conservation Branches. The Division of Animal Industry under M.R. Irving was made up of the Animal Health, Animal Husbandry and Dairy Branches.

By far the most significant new development was the establishment of a Division of Extension Services and Information under its Chief, R.I. Herriot, who was also designated Deputy Director of the Department. This division had relatively few staff of its own – the officers involved with publications and publicity, the library, the three extension support groups (Agricultural Bureau, Women’s Agricultural Bureau and Rural Youth Movement) and, most significantly, a Senior Extension Officer and a Senior Information Officer. The latter, supporting Herriot as Chief, were the principal channels through which the new Division would discharge its main responsibility of managing and supporting the work in the field of the extension officers of the Industry Division branches.

In point of fact, the heads of those branches were responsible to the Chief of the Division of Extension Services and Information for their branch extension and information programs. Thus for the first time in its history the department had part of its operations under functional rather than line management.

The first appointees to the new key positions were P.C. Angove and D.T. Kilpatrick, both extension workers with long departmental experience. After the promotion of Strickland and Irving as Industry Division chiefs, they were replaced respectively by T.C. Miller (recruited from the W.A. Department of Agriculture) and C.T. McKenna (promoted from within the Animal Husbandry Branch), while J.A. Beare was promoted from within his branch to the vacant position of Head of the Soil Conservation Branch.

Improved technology and stronger legislation for weed control

By the early 1950s there developed throughout the cereal growing areas of the State a deep concern about the increasing frequencies of skeleton weed invading from New South Wales. This aggressive weed had a potential to seriously reduce cereal crop productivity.

In 1951–52, Callaghan secured the appointment of five new Field Officers to support the increasingly effective work of Weeds Officer, Hector Orchard. Their specific aim was to eradicate skeleton weed.

Control of noxious weeds had historically been seen as the responsibility of local government, but the over-arching legislation had proved ineffective in getting many Councils to deliver timely weed control programs. An attempt had been made in 1949–50 to have the government introduce a stronger Weeds Act but in the face of concerted opposition from local government, this was not proceeded with.

Advances in weed control science (and the development of selective herbicides) along with the need to protect markets and the environment from weed seed contamination and weed invasion brought growing recognition of the need to strengthen control of the State’s noxious weeds. Callaghan took an active interest in these developments and strongly fostered the drafting of new weed control legislation which came into force as the Weeds Act 1956.

The new legislation gave great control obligation and gave greater powers to local councils to enforce weed control or eradication. It also defined two categories for designating weeds – dangerous (so seriously threatening as to warrant attempts at eradication) and noxious (serious weeds so well established or widespread as make eradication infeasible but requiring some measure of control or containment). The Act also gave the Minister of Agriculture the power to force councils to fulfil their weed control obligations.

The Weeds Act 1956 also contained a new element of great significance. It established a Weeds Advisory Committee, largely comprising people from local government, appointed by the Minister for their ability to contribute to the work of the Committee (from their proven experience in weed control at the local level).

Callaghan was the first Chairman of this new Weeds Advisory Committee and immediately brought his customary drive, enthusiasm and inspirational skills to bear, creating a new sense of achievement in tackling weed problems across the State. At the same time, he established within the Agronomy Branch a Weed Science Unit, under Hector Orchard, incorporating research, extension and regulatory functions. This set a benchmark for other States to follow during the 1960s and 1970s.

New weeds legislation introduced by Callaghan enabled control of problem weeds such as this wild artichoke near Gladstone in 1950.

Strengthening the weeds section

Following the death in a road accident of Hector Orchard, leader of the Weeds Section of the Agronomy Branch, Arthur Tideman was recruited in 1958 as the Senior Weeds Officer. Tideman had been a Departmental cadet and served for some years as a Soil Conservation Officer before resigning to take up a position as a technical representative with Shell Chemicals based in Clare. In that role he had gained a wealth of field experience in the burgeoning area of weed control technology.

This experience together with his general training in agricultural science and his developing management skills enabled him to build up and lead an outstanding weeds unit which grew to 17 officers over the next 12 years, and become something of a pace setter in the field. The unit’s combination of research, extension and regulatory roles helped make it a particularly effective operation.

Developing Agricultural economics

In 1956, the Department of Agriculture’s first agricultural economist, David Penny, was appointed. This position had been created in 1955 when some unfortunate experiences showed that input from a professional economist was necessary if the Department was to meet the increasing demands for programs which were soundly based on a professional understanding of farm management principles. It had become apparent that the Department could no longer rely alone on the often wide experience of officers with only limited training in economics.

The economist was initially under the supervision of the Scientific Liaison Officer but, following Penny’s resignation in 1957 and the appointment of his successor, Allan Dawson, was transferred to the Extension Services Division.

The adoption by the Department in 1957 of a “whole farm approach” to extension work required integration of advice given so that it matched the production pattern of each farm. This in turn emphasised the need for close liaison between farm management economists and technical advisers. Also at this time, one started to see the beginning of farm management groups where, in selected areas, a number of farmers came together to employ their own farm management consultant.

Extension training – new methods and skills

From 1946, the B. Ag. Sc. degree course had included a minor third year subject entitled “Methods of Extension”, delivered by the Deputy Principal of Roseworthy College who was not however well experienced in this field. A similar course was included in the Roseworthy Diploma of Agriculture courses of the time.

By 1953 there was a growing awareness in the Department, (even before the creation of the Division of Extension Services and Information) that there was a need to ensure additional training in communication skills and education philosophy for most advisory staff.

Herriot, as head of the Soil Conservation Branch and drawing on his training in education and experience in departmental extension programs, led the way by conducting residential in-service training schools aimed at, in time, training every Departmental staff member involved in advisory work.

These courses, with Callaghan’s strong sponsorship, were held at Roseworthy College and were conducted by Herriot and two other Departmental officers, acknowledged leaders in field extension practice, with support from outside specialists, e.g. in radio and print journalism. These week long training courses were held annually until every advisory officer had attended. The effectiveness of this program was improved from 1956 when the structure and staffing of the Division of Extension and Information Services was established. The program remained ongoing on a needs basis for many years.

Department of Agriculture administration

By the end of the Callaghan decade, the administrative structure of the Department, under the leadership of Secretary S.T. North, comprised several sections including an accounts branch; a correspondence (registry) branch; the Chief Inspector’s Branch (covering apiaries, fertilizer and pesticide registration, chaff and hay, stock foods and margarine quotas); a typing pool; and a data processing branch with punch card equipment replacing comptometers. In addition, clerical officers and one or two short hand typists were deployed with each of the divisions and technical branches, meeting the bulk of those units’ needs.

The specialised administrative functions of personnel work, procurement, stores, building maintenance and construction, transport and PABX telephone services were closely managed personally by Secretary Stan North with support in some areas by a specialist officer, e.g. transport and procurement or telephone services.

Move to Gawler Place building

Of considerable significance to the administration of the Department was the consolidation of virtually the whole of head office, between July 1950 and May 1951 at a single site in 133 Gawler Place – Agriculture Building, an office converted from Simpson’s old factory.

The five storeys and basement of this building accommodated not only the Department’s head office staff but also the Woods and Forests Department, the Supply and Tender Board and Chief Storekeeper, the Fisheries and Game Department, the office of the Minister of Agriculture Department and a staff canteen.

The Agriculture Building was an improvement for the formerly scattered units comprising the Department’s head office and the co-location of the Minister’s Office was a plus. The building was poorly ventilated, however, and with only a few rooms air conditioned, working conditions on hot summer days could become unbearable.

The 5 storey Agriculture Building (centre) on the west side of Gawler Place in 1952.

It was the Department of Agriculture’s head office until the move to 25 Grenfell Street in 1976. Source: State Library of SA File B12359.

Staff cadetships and skilling

The first cadetships – in effect, bonded university scholarships – to provide for a supply of graduate recruits had begun in 1938-39 (during Spafford’s directorship) and resumed after World War 2 (see “Skilling the Department’s Scientific Officers”). Under Callaghan’s leadership the scheme was greatly expanded. He saw this as essential to provide a continuing future supply of well-trained personnel across the whole range of professional expertise required by an expanding Department.

Skilling extension staff to become effective adult educators was given a high priority.

Potato variety field day, delivering new variety technology to potato growers at Woodside, February 1973.

The demand for research and advisory staff trained in agronomy, soil science, entomology, plant pathology and biometry would be well catered for within the options available through the upgraded four year University of Adelaide B.Ag.Sc. course. This course was, however, inadequate to provide the required level and spread of expertise for animal husbandry specialists and it had only a minor component of agricultural economics.

By the early 1950s, the University of New England at Armidale NSW had developed two excellent new degree courses which were recognised as capable of filling these gaps. The Bachelor of Rural Science degree gave a major emphasis to animal husbandry within a general agricultural framework while the Bachelor of Rural Economics degree was specifically designed to give first rate training in farm management economics. Both these courses were added as options in the cadetship scheme which already also included veterinary scholarships.

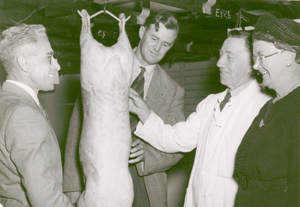

Dr Allan Callaghan (left) at a lamb carcass judging competition in 1955 with Senior Animal Husbandry Officer, Denis Muirhead (centre).

Graduating veterinarians had the choice of joining the Department as a government veterinary officer or entering into a farm animal private practice in a country area in order to serve out their three year bond. At the time, rural veterinary practitioners were rarities and the government was keen to see their numbers increase to provide individual animal health services for a fee to livestock owners, allowing the departmental veterinary staff to concentrate on flock and herd problems.

Relationships with Ministers of Agriculture

At the time of his appointment as Director and for some years thereafter, Callaghan enjoyed harmonious and productive relations with his Ministers. The first was Sir George Jenkins M.L.C., a pastoralist and long-serving Liberal and Country League Member of Parliament. He retired in May 1954 and was replaced by Arthur Christian, M.H.A., a farmer from Kimba on Eyre Peninsula.

Both men clearly admired and respected Callaghan and were supportive of his ideas for change and development of the Department.

When Christian died in January 1956 after suffering a heart attack while fighting a bushfire in his district, Premier Thomas Playford acted in the portfolio for some months before Glen Pearson M.L.A., a farmer from Cockaleechie, Southern Eyre Peninsula, became the new Minister of Agriculture in April.

Pearson was a much more ambitious politician than either of his predecessors, went on to become State Treasurer, and received a knighthood. As Minister of Agriculture he was less willing than Jenkins or Christian to go along with Callaghan and may well have been influenced by Playford’s concern that his director was too intent on “building new Waite Institutes”. He also, as a farmer, had his own views about agriculture services, especially on the way research stations should be run.

A classic case was his refusal to approve the building of a new woolshed at Minnipa, designed to facilitate the handling of small numbers of sheep undergoing different experimental procedures and to keep separate the wool clip of each small group. When Pearson could not be persuaded of the need for such a design, the issue – along with a number of others where Minister and Director could not agree – became a great source of frustration to Callaghan. Another sign of the changed relationship was Pearson’s decision to move his office and small department out of Agriculture Building to Education Building, closer to the Treasury and other ministerial offices.

Callaghan’s illness, resignation and later career

The deteriorating relationship with Pearson, together with the increasing pressures of public life, led to Callaghan’s serious illness. He suffered from recurrent attacks of paroxysmal tachycardia, causing reduction of oxygen supply to the brain and temporary collapse.

There seemed to be no prospect of a cure for or management of this complaint and in 1959, Callaghan resigned because of ill health. Relieved of the tension which had oppressed him in the later years of his directorship, he made a full recovery.

Callaghan went on to serve with distinction as Australian Commercial Counsellor in Washington, D.C. (1959–65) and as an outstanding Chairman of the Australian Wheat Board (1965–71). He was knighted in 1972 for his performance in this latter role.

He once again was to serve the South Australian Government in 1973 when he researched and prepared a major report entitled “A Review of the Department of Agriculture in the Light of Changed and Changing Needs”. This document was accepted by the government and its recommendations became reference points for much of the development of the Department over the following decade.

Callaghan remained in good health for the rest of his life which ended in 1993 at the age of 90 years.

Callaghan was highly influential, using his vision and multiple talents to totally transform the South Australian Department of Agriculture during a period of rapid growth and development in the post-war years. This was achieved without losing its ethos of service to the State’s rural industries and producers.

Other initiatives during Callaghan’s term

Following are brief descriptions of other major changes in the Department, largely driven by Allan Callaghan’s personal initiatives and creativity. At the same time, a number of other significant events must also be recorded.

Research centres

In the early 1950s, all the departmental research centres were upgraded and their management more strongly directed to identifying and trying to solve local farming or horticultural problems.

The Kangaroo Island Research Centre at Parndarna was established in 1959–61, and the Wanbi Research Centre was acquired as a base for soil conservation research in the Murray Mallee. Soon after, the old Parafield Research Centre, located alongside its Poultry Research Station cousin, began to be redeveloped as a centre for plant introduction and the evaluation of new pasture species and cultivars.

The opening of the major new soldier settlement irrigation area at Loxton led to the establishment of a new horticultural Loxton Research Centre which eventually replaced the old Berri Experimental Orchard.

The significance of the Ligurian bee colonies on Kangaroo Island as the only pure population of this bee strain in the world was recognised and steps taken to protect it from genetic contamination. This led to a substantial international trade in Ligurian queen bees.

Home Gardens Advisory Service

When the Horticulture Branch moved into Agriculture Building, it used its team of young research officers to strengthen a regular service to home gardeners on fruit and vegetable growing problems. These officers arranged their field programs so that they could man a roster for home gardens advice, five days a week. In 1976, a dedicated team of three officers were appointed to service home gardeners and urban communities.

Biometrical services

Again, these services to ensure that experiments were soundly planned and results statistically analysed, were at first developed in the Horticulture Branch where a young laboratory assistant (K.M. Cellier) was encouraged to undertake part-time studies for a B.Sc., majoring in mathematical statistics. His primary responsibility was to the research officers of his own branch but, by arrangement, he also became involved in assisting the staff of other branches, notably Agronomy.

Fruit fly infestations

Throughout the Callaghan decade, fruit fly outbreaks continued to occur, mostly in the Adelaide metropolitan area, but occasionally in country towns. The Horticulture Branch developed considerable expertise in managing the annual eradication campaign and employing seasonal staff for spraying and fruit removal. Eradication costs averaged about £100,000 p.a. and compensation, paid at that time to householders whose fruit was stripped, ran at some £30,000 p.a.

From 1959 the State’s defences against introduction of both Mediterranean and Queensland fruit fly species were strengthened by establishing road blocks at Yamba (near Renmark), Pinnaroo, Oodlawirra (on the Broken Hill road) and Ceduna.

The Yamba fruit fly inspection point for vehicles entering the Riverland in 1959.

Soil conservation

The work of the Soil Conservation Branch continued unabated throughout the 1950s. Inspection of native scrub land as a prerequisite to approval to clear which had begun in 1946 was at first a major activity for branch staff. However, as the areas of land acceptable for clearing began to dwindle, attention was increasingly turned to soil erosion issues in the higher rainfall, mixed farming areas.

Surveying properties preparatory to the construction of contour banks to prevent water erosion and for the location of dam sites soon became a service widely sought, especially in the Lower and Mid-North. This in turn led gradually to the adoption of general farm planning as the basis for future property management in the mixed farming areas.

Bovine Pleuro-pneumonia

In 1953–54 the first steps were taken, by testing store cattle coming into South Australia from the Northern Territory, to prevent the spread of pleuro-pneumonia amongst the State’s herds. This was one of the initial moves which in due course led to a nation-wide program to eradicate this disease.

Further information on eradication of bovine pleuro pneumonia

Locust control

By 1955 numbers of the Australian plague locust had built up with extensive egg laying in the pastoral areas in the north of the State. Research by scientists in the CSIRO Division of Entomology and the Waite Institute Entomology Department provided a new basis for a strategy to minimise the damage likely to be caused to crops, pastures and orchards when swarms flew south.

The government invoked the provisions of the Noxious Insects Act and a massive campaign, managed by the Department of Agriculture and involving District Councils, land holders, the Australian Army and the agriculture aviation industry, was developed.

Identification of emerging hopper bands and monitoring them as they combined and moved south, using new, more effective insecticides and much improved spraying equipment, made this approach more economically feasible and, together with the strategic use of aerial spraying of winged locusts on the ground in cool mornings and evenings, resulted in major success.

The plague was stopped at Tarlee, in the Lower North. It was estimated that the expenditure of special funds – of the order of £172,000 – probably saved farmers and orchardists about £10 million.

A major part was played by district and head office staff of the Department of Agriculture, with about 40 officers seconded from their normal duties to coordinate and supervise the huge effort required to achieve this success.

Tiger Moth aircraft used for aerial spraying of locust plagues in the late 1950s.

Legislation

In 1956, the Minister of Agriculture was empowered by two acts of Parliament to greatly strengthen the regulatory role of the department.

The first of these was the Weeds Act, its significance has already been described earlier in this article. The second was the Agricultural Chemicals Act 1956, which brought together under the one statutory umbrella the registration and control of all fertilizers, pesticides and the like with the exception of veterinary medicines which remained under the existing Stock Medicines Act 1939. The rapid proliferation of newly-developed chemicals for control of insect pests, fungal disease and weeds and as additives to fertilizers required a major upgrading of the law to ensure appropriate standards of labelling, purity and efficiency were set and observed.

Crop and pruning competitions

The long standing crop and pruning competitions, much beloved by the Agriculture Bureaux movement, were reviewed because many were not achieving significant extension objectives. Some were abolished or restructured to deliver better value. Fruit and vine pruning was in any event, becoming less formalised as lower costs were pursued.

An interesting change in wheat crop competitions was the introduction of the concept of efficiency in cereal growing whereby crop yield was rated in proportion to the local seasonal rainfall.

Moves toward regional concepts of service delivery

As previously mentioned, the Department’s major research centres were being encouraged to develop a strong consciousness of the farm and orchard problems of their area in planning their research programs. On the extension services front, in 1958–59 improved regional advisory centres were being developed at Cleve, Murray Bridge, Naracoorte and Nuriootpa.

In the Agronomy Branch, a Senior Agricultural Advisor had been appointed a couple of years before to coordinate the work of the dozen or so district advisors.

Artificial insemination of dairy cattle

The use of stud bulls to directly inseminate dairy cows was starting to be seen as less efficient in the building and maintenance of genetic quality in the dairy industry. In 1957-58 supervised artificial insemination services were introduced on an exploratory basis.

This service was handed over to the Artificial Breeding Board following its establishment. It had bull housing, semen collection and distribution facilities at Northfield.

Central laboratories and field experiment facilities

For some time, the department had been making noises about the need for central laboratory facilities (virtually non-existent) and an area for agronomic and animal field studies (very limited at the time). In the late 1950s, the SA Government decided that the extensive tuberculosis hospital at Bedford Park was no longer needed because of greatly improved treatments for that disease. A number of Departments, including Agriculture, were asked to set out in broad terms including rough estimates of costs how they would use some of the area if it were made available to them.

The Department of Agriculture saw this as an opportunity to acquire new research and analytical facilities, and made a submission in accordance with parameters laid down by Cabinet. The Government ultimately decided to use the Bedford Park site for the State’s second university (Flinders) and a major public and teaching hospital (Flinders Medical Centre).

The need for more extensive research facilities was resolved a few years later when the old mental hospital farm at Northfield was developed to become Northfield Research Laboratories and the Dairy Research Centre.

Callaghan’s national influence

During his tenure as Director of Agriculture, Allan Callaghan was also extremely influential in matters of national agricultural significance. While this is peripheral to the history of the SA Department of Agriculture, much of it emanated from Callaghan’s status and the way in which he performed his Directorship.

For most of the 1950s, the Standing Committee on Agriculture membership was arguably the strongest it has ever been. The two major Commonwealth representatives – Sir John Crawford of Commerce and Agriculture and Sir Ian Clunies Ross of CSIRO – were towering public figures at that time. Five of the six State representatives - Arthur Bell (Queensland), George Baron-Hay (WA), Robert Noble (NSW), Hubert Mullett (Victoria) and Callaghan (SA) – were each a highly respected and effective leader and spokesman for his State’s rural industries and institutions.

Amongst this high-powered group, Callaghan was a key member frequently bringing forward fresh ideas across a whole range of agricultural issues.

In particular, he strongly supported the moves which led to the development of the highly significant Commonwealth agricultural industries schemes which brought greatly increased funding for the applied research and extension services in all States.

Callaghan also played a key role in securing agreement between the States and the Commonwealth for joint funding of a new journal to independently publish refereed scientific papers on applied research projects, the “Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture and Animal Husbandry”.

Outside the Standing Committee arena, Callaghan, was national president of the Australian Institute of Agricultural Science. In 1956, he strongly supported a move by its Victorian branch to establish a permanent central office, employing a full- time executive officer with support staff, to enable the Institute to more effectively formulate and voice the views of professional agricultural scientists. Furthermore, he was able to convince J.G. Crawford that it was in the national agricultural interest to support this move by providing substantial funds for a few years to get the central office set up and running.

Together with Dr A.J. Millington, Reader in Agronomy, University of Western Australia, Callaghan was senior author of a 480 page book “The Wheat Industry in Australia” (Angus and Robertson, 1956). This quickly became and remained for many years the definitive text book on its topic.

He also developed a keen interest in seeking a major change in the marketing of Australian wheat which at the time was still based on the FAQ system. In 1956, he undertook a study tour as a Carnegie Travelling Fellow to Canada, and observed well established marketing schemes based on separation of wheats of differing qualities. This reinforced his belief that the Australian wheat marketing system needed modification to provide for the separation of high baking quality grain. The necessary changes, however, were not to come until 1967 during his term as Chairman of the Australian Wheat Board.

And finally, in the period of his directorship he received two honours recognising his outstanding contributions to Australian Agriculture. One was the Farrer Medal, awarded in 1954 by the William Farrer Memorial Trust, while the other was in 1958 to be elected as one of the first Fellows of the Australian Institute of Agricultural Science, the highest recognition within the profession.

Further reading

Callaghan, Allan R. (Allan Robert), (Sir) (1903-1993) on Trove

The author

This article was researched and written by Peter Trumble, a retired Deputy Director General of the Department of Agriculture.