The Perkins era 1914–1936

Born in Egypt in 1871, Arthur James Perkins went on to study the diploma of the Ecole Nationale d’Agriculture at Montpellier in France (1887–90) specialising in viticulture.

Arthur James Perkins

Early career

He spent two years managing properties in Tunisia before being recruited to become Government Viticulturist based at Roseworthy Agricultural College in 1892.

At Roseworthy College, he taught viticulture, wine making and fruit culture, and also lectured on these topics in horticultural growing districts across South Australia. He established the vineyards and winery at Roseworthy College, and played a key role in developing quarantine measures to prevent the introduction of phylloxera into South Australia. His skills were vital in early development of SA’s wine industry, and establishing and administering quality standards for export wines.

In 1902 he was appointed editor of the South Australian Journal of Agriculture, then, in 1904 was appointed principal of Roseworthy Agricultural College. In this role he gained further experience with selection of improved wheat varieties, digestibility of foodstuffs for stock, fat lamb breeding, and cereal nutrition and seeding techniques.

In 1914, Arthur Perkins succeeded William Lowrie as the SA Department of Agriculture’s Director of Agriculture. This article describes the major achievements from the 22 year period of Perkin’s directorship.

Arthur Perkins retired in 1936, and wrote a number of articles in his retirement. He was awarded an OBE in 1937, and died on 23 June 1944.

Early developments in Perkins’ directorship

The work of the Department and related services were significantly affected by the Great War of 1914–1918. In those days rural industry was very dependent, literally, on horse power, as was the army and the general community. Early in the war a Grain and Fodder Board was established “to ensure that there will be sufficient supplies of grain and fodder available for the use of persons requiring the same”. Many departmental staff assisted the Board in assessing the needs of farmers and others for fodder reserves, much limited by the serious effects of the 1914–1915 drought.

Some staff of the Department joined the armed services and the work of the Stock and Brands Department was badly disrupted when both Assistant Veterinary Officers enlisted for the duration of the war to help meet the needs of the Australian army, giving their professional services to support the great numbers of horses used in both fighting and transport units.

Important appointments were made to the Department’s agricultural investigations group. Bill Spafford left Roseworthy College in 1914 to become Superintendent of Experimental Work and L.J. (Len) Cook was appointed as the first manager of the newly acquired Eyre Peninsula Experimental Farm at Minnipa. Len and his wife had to live in a tent for over a year before the first staff houses were built.

An early view of Eyre Peninsula Experimental Farm. The site was originally selected by Prof Perkins in 1914.

It was ultimately developed into the Minnipa Agricultural Centre after World War 2 and became the main research facility servicing Eyre Peninsula.

In 1917–18, J. Paull was appointed as Field Engineer, to oversee building work on experiment stations and orchards and to teach agricultural engineering at Roseworthy College. By 1920–21 his activities had been widened to include building advisory services for farmers but after he died suddenly a year later, the position was abolished.

In mid-1917 the Department's seed testing service was established, mainly to provide data to seed merchants on germination percentages. The seed testing laboratory was maintained as an adjunct to Head Office where it was readily accessible to its principal clients. It was transferred to the Plant Research Centre at the Waite as part of the co-location program in the early 1990s.

The first Government provision for specific financial assistance to rural producers came in 1920–21 when a Loans to Producers Board was established. Its purpose was to make loans at concessional rates to land holders and producer cooperatives for the purchase of equipment for product processing or the construction/installation of storage facilities and irrigation systems.

The first District Advisory Services

In 1917–18, the first advisory officers located in country districts were appointed. They were titled “Orchard Instructors and Inspectors” combining extension work with regulatory duties. There were five of them at this time, servicing the South East, Southern District (Fleurieu Peninsula), Mt Lofty Ranges, Northern Adelaide Plains, and Northern Districts (Barossa and Clare Valleys and Wirrabara).

An Agricultural Instructor for the Mallee Lands was appointed in 1921–22 to assist the soldier settlers who were starting out on their farms in the Mallee. This region was opened up for cereal growing stimulated in part by the new railway lines radiating north and east from Tailem Bend.

The dairy industry started to get the same sort of service in 1925–26 when five District Dairy Instructors were appointed. In the same year four more farming districts were provided with Agricultural Instructors – Northern, Eyre Peninsula, Central and South East – to join the earlier Murray Mallee District. Colin Scott was recruited from Roseworthy College to become Chief Agricultural Instructor and a year later, two more agricultural instructors were added – in the Lower North and Upper Eyre Peninsula.

Thus in the decade 1917–27 the district-based extension service under George Quinn in horticulture, Colin Scott in the farming and grazing areas and “Lofty” Barlow for the dairy industry was established. This advisory structure was subsequently used by the Department for more than 70 years.

The Agricultural Bureau System

During Perkins’ term as Director and for many years thereafter, the branches of the Agricultural Bureau became the mainstay of the Department’s group extension work. By 1930 there were over 300 branches spread throughout the agricultural and horticultural areas of the State with nearly 8,500 members. In 1917–18 the newly-created Women’s Agricultural Bureau formed its first branch and grew steadily over the next 40 years.

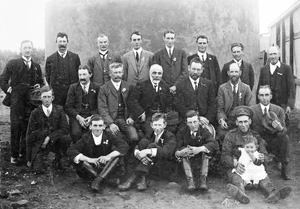

Members of the Hartley Agricultural Bureau in 1918. One of many Agricultural Bureaus established in South Australia to distribute information to the farming community.

Source: State Library of SA file PRG 280/1/9/166.

These parallel organisations remained steadfastly non-political which ensured that their sole focus was on adult education for farmers and farm families, leaving political issues to the various producer associations and the Country Women’s Association.

The Bureau branches became less involved in local experimentation and variety testing. As the department’s resources grew; experiment stations and orchards developed in number and in technical capacity. Departmental trials and experiments on farmers’ and orchardists’ properties also spread throughout the State.

The Bureau system and the S.A. Journal of Agriculture were the principal avenues for group extension work and provision of information. Branches met monthly, often in rotation at members’ homes but also in local halls. Until the 1930s the dates of meetings were often set to align with the full moon to make night-time travelling safer for those who did not yet have motor cars.

Branches or groups of branches established crop competitions in many districts and, in the horticultural areas, fruit and vine pruning competitions. These were strongly supported by farmers and orchardists and there was keen competition for trophies of significant value.

George Quinn was Australia’s acknowledged expert on tree and vine pruning. He used the pruning competitions and associated demonstrations to foster a high degree of skill amongst growers of stone fruit and grapes. The neatly trimmed, uniform winter appearance of the State’s orchards and vineyards were a tribute to his enthusiasm and expertise.

George Quinn demonstrating pruning techniques in 1918. Although his title was Horticulture Instructor, effectively he was Deputy Director of the Department of Agriculture under Arthur Perkins until his retirement in May 1935.

Source: State Library of SA file PRG 280/1/10/433.

Horticultural inspectors

During the early part of this period, horticultural inspectors were responsible also for inspection of chaff and hay, fertilizers and other agricultural chemicals and of apiaries, continuing the system which had begun in the 1890s with George Quinn’s appointment.

In the early 1930s, as Quinn approached retiring age, A.G. Strickland, a Melbourne University agriculture science graduate and holder of a master’s degree, was appointed as Quinn’s deputy. At the same time, a Chief Inspector’s Section, responsible to the Director, was formed under D.L. Mack to take over the non-horticultural inspections. This freed horticultural staff to concentrate their efforts on the implementation of the Vine, Fruit and Vegetable Protection Act, the Sale of Fruit Act, the Prevention of Injury to Fruit Act, fruit grading regulations and their role as agents for the Commonwealth export and plant quarantine authorities.

Mack’s section from 1935–36 also carried out the inspections required under the new Margarine Act aimed at reducing the ability of table margarine to compete with butter.

Service to the dairy industry

At the beginning of Perkins’ reign, herd testing associations started to form to provide dairy farmers with objective measurement of the butter fat production of their individual cows. These associations, although strongly encouraged by Dairy Instructor Suter, were purely voluntary and received no government financial support. This changed with the passing of the Dairy Cattle Improvement Act 1921, which provided for bull licensing, with the licensing fees being used to fund subsidies on the purchase of approved dairy bulls and for the financial support of herd testing associations. At first there were only two such associations – at Murray Bridge and Mt. Gambier.

The herd testing movement thrived and there soon were three associations with some 1500 cows under regular test, growing to four, representing 1800 cows, by the end of Perkins’ term of office.

Federation and agricultural services

The constitutional powers concerning rural industries are split between the Commonwealth and the State Governments. The Australian Constitution reserves to the Commonwealth Government sole powers regarding all external matters (e.g. import and export trade, quarantine). Some powers are shared and residual powers are left to the States. This means, in effect, that agricultural production is a State sphere while marketing of agricultural products is shared. However, Section 92 of the Constitution makes it very clear that trade between the States shall be “absolutely free”.

Since Federation in 1901 there had been many ad hoc conferences of State Ministers of Agriculture, often with the relevant Commonwealth Ministers. State Directors of Agriculture had also held conferences from time to time to sort out particular problems as they arose. But in the late 1920s and early 1930s events conspired to cause the establishment of mechanisms for regular meetings of the State and Commonwealth Ministers with the aim of deciding on and implementing nation-wide action for the benefit of agricultural industries. Factors contributing to this development were:

- the successful High Court challenges against the Commonwealth to prevent attempts to legislate for national marketing schemes;

- the massive effect of the Great Depression on rural industries; and

- increasing political will to tackle rural problems on a nation-wide basis, stemming in part from the successful establishment of the Country Party in 1927.

Thus, in 1934 the Australian Agricultural Council was set up, chaired by the Minister for Commerce and Agriculture, with each State Minister of Agriculture a member. The Chair transferred to the Minister for Primary Industry when Commerce and Agriculture were split in the 1950s, and the Ministers for Trade and for Territories were added.

The Australian Agricultural Council was served by a Standing Committee on Agriculture comprising the six State Directors of Agriculture (among whom the chairmanship rotated annually) and a number of representatives of Commonwealth agencies concerned with agriculture. These Commonwealth representatives varied from time to time but usually included Commerce and Agriculture (until replaced by Primary Industry and by Trade), Bureau of Agricultural Economics, Territories (included New Zealand and New Guinea representatives), Health (plant and animal quarantine), Treasury (a very useful inclusion!) and CSIR/CSIRO.

The Council met regularly, usually twice a year (alternating between Canberra and State Capitals in rotation) but also as required at critical times. Its meetings were immediately preceded by two or three day sessions of the Standing Committee. The Committee considered all matters of concern to Australian agriculture, as listed by any party, and made recommendations to the Council for action when policy or financial issues arose. Some matters took several meetings to finalise at the Committee level while others, essentially administrative or within recognised guidelines, were deemed not to require Council approval.

The Standing Committee’s agenda also normally included a section labelled “Research Items”, largely but not solely initiated by CSIR/CSIRO.. These discussions could be held and agreement reached on significant research issues, especially co-operative research programs and proposals to hold national scientific and technical conferences.

The Australian Agricultural Council usually managed to achieve consensus of all governments, sometimes after several meetings. Occasionally the required unanimity (e.g. on marketing plans requiring complementary legislation involving the Commonwealth and all States) was not achieved on some key point. These matters would then be referred to a Premiers’ Conference for resolution.

The Council and its Standing Committee over the years proved to be a very effective mechanism for making Federation work in agricultural matters, especially in regard to orderly marketing schemes and inter-governmental co-operation. There was a general recognition that the two levels of Government had to work in partnership for the good of agriculture.

The system enabled the South Australian Department of Agriculture to play its part in the national agricultural arena and Arthur Perkins, as its inaugural representative on the Standing Committee, brought the benefit of his natural abilities, and long experience to the table, making his mark on the Committee’s deliberations in the short time before his retirement. This Standing Committee process is still in use.

Stock and brands department

The Stock and Brands Department had its genesis in 1865 with appointment of C.J. Valentine as the first Chief Inspector of Stock. It subsequently operated in parallel with the Department of Agriculture. Its operations were strengthened by a new Brands Act in 1913 and its service capacity enhanced by the appointment of a veterinary pathologist in 1929–30.

Moves to require the registration of veterinarians had begun in 1917–18 but did not come into effect until a Veterinary Surgeons Board was established under the aegis of the Minister of Agriculture in 1935.

This Stock and Brands Department was amalgamated with the Department of Agriculture in 1944 but operated throughout the Perkins era in its own right to perform its statutory duties of animal disease control at the flock and herd level.

Changes among experiment stations and orchards

During the Perkins era there was a decline in the number of experimental stations. Kybybolite remained an experiment station while the experimental orchards at Blackwood, Berri and Hackney continued to be developed. Turretfield became a seed wheat farm and Minnipa was being share-farmed. Veitch’s Well and Booborowie were closed. The Parafield Poultry Station remained as a focal point for the poultry industry.

Changes at Roseworthy College

A strike by students in January 1932 led to a Royal Commission into Roseworthy College management and student behaviour. This investigation brought down an open verdict but rather favoured the grievances felt by students. Principal W.R. Birks resigned in April and W.J. (Bill) Spafford was seconded from the Department of Agriculture as Acting Principal until newly appointed Principal, A.R. Callaghan could take up his position in July.

The advent of the young, dynamic Callaghan signalled a remarkable revitalisation of Roseworthy College. This included a major upgrading of the plant breeding program, and the establishment of Australia’s first diploma course in oenology. The conduct of demonstration trials on prime lamb breeding and ley farming, and considerable activity in extension programs resulted in farmers’ field days at the College being particularly well attended and successful.

Major staff changes

As Perkins neared retiring age, a number of changes of personnel occurred. George Quinn, who had been in charge of the Department’s horticultural services for 40 years, retired in 1934 to be replaced by Geoff Strickland, recruited from the Victorian Department of Agriculture. Strickland later became South Australia’s Director of Agriculture. Quinn and Perkins had been the principal architects of the State’s protective measures against the entry of the devastating grape vine pest, phylloxera. Largely through the agency of the Phylloxera Board, phylloxera never gained a foot-hold in South Australia. This laid the foundation for the pre-eminence of South Australia in the Australian wine industry.

The first poultry expert, D.F. Laurie, retired in 1929–30 and was replaced by Cyril Anderson who had been Manager of the Parafield Poultry Station where work on poultry rations and housing had under-pinned the huge boom in egg exports in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The work of L.J. Cook at Kybybolite on the top-dressing of pastures with superphosphate led to a four-fold increase in this practice in the five years to 1939-40. He took over the role of Chief Experimentalist as Spafford and Scott were promoted to senior management roles.

The creation of a Chief Inspector’s section to take over certain regulatory responsibilities from the Horticulture Branch has already been mentioned.

The development of specialist scientific services

During the early part of his directorship, Perkins played a key role in developing scientific support services for agricultural industries.

As awareness of the nature of pests and infectious diseases and the recognition of the need for accurate identification of plants grew in the latter part of the 19th century, the embryonic Department of Agriculture had no specialists of its own in these fields. It made the best use it could of the experience of senior staff and the study of the available scientific literature.

The Departments of Agriculture in New South Wales and Victoria, by this time, had entomologists and plant pathologists on their staffs. These men were the Australian pioneers in those disciplines and were frequently consulted by correspondence from South Australia. In 1891–92 there is reference to visits to South Australia by “inter-colonial experts”. These are likely to have included C. McAlpine (NSW plant pathologist) and D. French (Victorian entomologist) who would have provided the best advice available in Australia on specific disease and pest problems.

It was not until 1910 that the South Australian department, under Angus’ leadership, entered into an agreement with T.G.B. Osborn, Professor of Botany at the University of Adelaide, to provide a consultancy service in plant identification and plant diseases. His reports on these services appear regularly in the annual reports of the Minister of Agriculture from 1917–18 until the establishment of the Waite Institute in 1924.

The Botany Department’s consultancy, especially in plant pathology, was placed on a firmer footing in 1920–21 when Geoffrey Samuel was appointed as assistant to Osborn, specialising in fungal diseases of plants.

In the meantime, a State Agricultural Chemist was added to the staff of Roseworthy College in 1917–18 and no doubt supplied analytical services on soil and fertiliser samples furnished by the Department of Agriculture. In 1922–23, it was reported that an entomologist at the SA Museum was available “at call” for identification of insect pests.

Except in the case of plant pathology, these scientific services to the Department were not much more than token until the Waite Agricultural Research Institute was established in 1924 at Urrbrae as a new unit of the University of Adelaide.

Creation and development of the Waite Institute

Mr Peter Waite, a wealthy pastoralist and businessman wrote to the Premier (The Hon A.H. Peake) on 15 October 1913 offering a gift of approximately 100 ha of land which was subsequently used for establishing Urrbrae Agricultural High School and Waite Agricultural Research Institute.

In this letter, Mr Waite stated;

“….I have now arranged to hand over to the University of Adelaide my “Urrbrae” house and grounds, embracing an area of 134 acres, half of the land to be available for University for agricultural and kindred studies, and the balance as a public park under their control”.

The second part of this bequeath was an offer to the SA Government for

“…..part section 250, Hundred of Adelaide, containing 114 acres for the purpose of an agricultural high school; this land adjoins Urrbrae”.

In 1915, the University appointed a special committee to make recommendations on how to go about setting up the proposed “Agricultural Investigation Station”, appointing a director and other staff and securing future funds for its operations. Arthur Perkins was a member of the University Council and was a key member of the special committee. He had known Peter Waite well, had discussed the proposed new investigation station with him, and played a major part in drafting the committee’s recommendations.

In what later became a significant stumbling block to bringing Peter Waite’s dream to fruition, the report stated, at Item 15(b):

“The appointment of a Director who amongst other things should be a thoroughly competent agriculturalist …….”.

Peter Waite was known to support this view.

After Mr and Mrs Waite died, the University proceeded to implement the bequest. In discussions within the university in 1923 some leading academics strongly expressed a different view to that inherent in Item 15(b), cited above. They believed “that the Director should be distinguished for his personal ability as an investigator and should have an acknowledged reputation for his contribution to knowledge of previously unknown facts. Broad understandings and some administrative talents were desirable no doubt, but research ability should take precedence over all other qualifications”.

The matter proceeded very slowly while these two views were debated for a year or so within the University. Perkins felt that his (and Mr Waite’s) concept of the leader of the new institute was being railroaded by organised opposition of academics, supported by the Vice-Chancellor. This, together with frustration at continuing delays, led Perkins to resign from the University Council in December 1923.

Some six months later, Vice-Chancellor Mitchell found a way out by creating two foundation chairs, one to be filled by a scientist of high research standing and the other by an outstanding man with broader qualities. In the event, A.E.V. Richardson (former Assistant Director of the SA Department of Agriculture and by then head of the Faculty of Agricultural Science at Melbourne University) became Director and Professor of Agriculture while J.A. Prescott, an outstanding soil scientist, was appointed Professor of Agricultural Chemistry.

Things moved swiftly thereafter with the appointments of an agricultural chemist, an agronomist, a plant geneticist, a field officer and a clerical officer and the transfer of Geoff Samuel from the Botany Department (University of Adelaide) as plant pathologist. The first laboratories were set up in the old Waite stables. A glass house was built and the first field experiments were laid out. Plantings began in what was to become the magnificent Waite Arboretum.

In 1927, following discussions between Richardson, the Vice-Chancellor and the Minister of Agriculture, the Agricultural Education Act, 1927, was passed, providing an annual State Government grant, increasing from £5,000 in 1927-28 to £15,000 in 1936-37 (approximately $A350,000 to $A1,000,000 in 2010 values). In return, the University agreed, through the new Institute, to conduct a wide range of research in disciplines relevant to agricultural production, to introduce and maintain a degree course in agricultural science, and to furnish advisory services to the Minister of Agriculture in plant pathology and entomology.

The staff of the institute embraced their responsibilities with enthusiasm. Over the next three decades, not only were the scientific advisory services in plant pathology and entomology (along with systematic botany) effectively maintained but also many research programs yielded valuable results for South Australian farmers. Some examples include:

- Introduction or development of improved pasture species (phalaris, strawberry clover, barrel medic)

- breeding of significant wheat varieties (Warigo, rust-resistant forms of popular susceptible varieties by back-crossing)

- certification of apple export shipments for freedom from San José scale

- rainfall, evaporation and drought frequency tables for every South Australian farming centre

- a field key for identifying pasture grasses and legumes by vegetative characteristics alone

- identification of the cause of grey speck disease of oats as manganese deficiency

- identification of alternative plant hosts involved in the spread of apricot gummosis

- studies of the behaviour of the Australian plague locust

- amplification of the basic CSIRO research on the need for trace elements in some sandy and ironstone soils

- development of a service for supply of appropriate Rhizobium cultures to improve nodulation rates in newly sown pasture legumes

- defining the pasture potential of the South East.

Waite Institute staff conducted numerous experiments on farmers’ and orchardists’ properties through much of the state during this period.

In addition, many technical reports and advisory articles were published in the SA Journal of Agriculture, as well as more popular items appearing in the rural press. Once the Australian Broadcasting Commission began its Country Hour and other rurally-orientated programs, Waite Institute staff often appeared as speakers or in interviews.

From 1937–38, the State grant to the Waite Institute remained unchanged for seven years at £15,000 but as a result of representations by the University, increased to £25,000 pa in 1949.

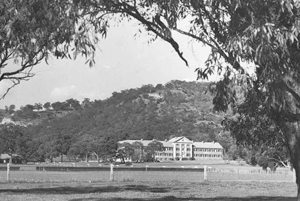

Waite Agriculture Research Institute c 1940. Source State Library of SA Image B61571

In 1947 the Minister of Agriculture appointed a committee under the Chairmanship of the Director of the Waite Institute (J.A. Prescott) to consider the relative responsibilities of the Department and the Institute in the fields of research, advisory services and general public education in agricultural practices. It was not until 1949, after A. P. Rowe had served a year as the University’s first full-time Vice-Chancellor, that a decision was announced.

This new basis of relationship between Department and Institute officially recognised that, apart from its responsibilities for teaching the agricultural sciences at university level, the Institute’s prime function was fundamental research having relevance to agricultural, pastoral and horticultural industries. The Institute’s advisory services would continue on a greatly modified scale, being confined to consultation and specialist advice on specific problems referred to it by the Department. The Department would undertake the extension work necessary to promote the application of the Institute’s scientific discoveries in a practical way amongst primary producers.

By 1952 the State Government ceased to make an ear-marked grant to the University for the purposes of the Waite Institute and the latter’s financial provisions thereafter relied upon its slice of the general resources cake as allocated by the University Council, together with whatever research grants it could secure.

Thus, after a little over a quarter of a century, the “special relationship” between the Department and the Institute formally came to an end, although the ensuing years were characterised by frequent cooperative research projects between elements of the two organisations and continuous consultation at the individual staff member level, until a major redevelopment of relationships took place in the 1990s.

Further reading

Richardson A.E.V. (1928); Waite Agricultural Research Institute Investigations in Progress, Bulletin No 221, SA Department of Agriculture.

The author

This article was researched and written by Peter Trumble, a retired Deputy Director General of the Department of Agriculture.