The Irving Years and Acting Directors 1970–1976

Geoff Strickland became very ill with cancer in late 1969 and died in January 1970. Marshall Roland Irving, BVS, HDA, Chief of the Division of Animal Industry, had been the nominated deputy to Strickland following R I Herriot’s appointment as Principal of Roseworthy College in 1964, and was Acting Director during the last stages of his predecessor’s illness. He was appointed as the Director of Agriculture in early 1970.

Marshall Roland Irving

The 1970s were characterised by great change for most of Australia’s rural industries. Declining export prices and markets coincided with rising costs of production. Many major industries recognised the need for limitations on production and the desirability in many areas for farm rehabilitation and debt reconstruction. Throughout Australia there was increasing emphasis on the pursuit of efficiency and improved productivity.

Under Irving, the department strove to sharpen the focus of its applied research and extension programs to meet the challenges being faced by South Australia’s rural industries. The late 1960s and early 1970s were also a period of substantial staff growth. A major driver was expansion of national funding via the Commonwealth Extension Services Grant program.

During his tenure as Director, Marshall Irving was often absent with recurrent periods of illness. This required his Assistant Directors to manage Department of Agriculture operations for extended periods. He was forced to retire because of ill health on 11 February 1975. In March 1975, Peter Trumble was appointed as Deputy Director and was Acting Director until Irving’s successor commenced duty in July 1976.

Creation of a departmental executive

Marshall Irving’s major contribution to the organisational development of the Department was to secure, for the first time, the formation of an executive group, analogous in many ways to the Board of Directors of a company.

A year after his appointment as Director, his recommendations to the Public Service Board bore fruit with the advertisement of three new Assistant Director positions. Rather than having a line management responsibility, these positions were focussed on the following functions:

- oversight of all research and extension activities, including the management of departmental applications for grants to outside bodies.

- regulatory activities and the Department’s relationships with primary producer representative groups and other relevant organisations.

- service areas of administration, accounting, financial and human resources management, in particular the coordination of these areas with the department’s technical, scientific and regulatory operations.

The first appointees were:

- A J K Walker as Assistant Director – Research and Extension (and designated Deputy Director)

- P McK Barrow as Assistant Director – Technical and Industry

- H P C Trumble as Assistant Director – Administration and Finance.

Walker and Barrow took up their new roles in April 1971 from positions within the Department. However the executive group was not complete until 1 June 1971 when Trumble took up his post. Trumble had worked the previous nine years at CSIRO Head Office and as Secretary (Chief Administrative Officer) of the Waite Institute. Prior to these appointments, he obtained a Public Administration Diploma. V K Lohmeyer, Scientific Liaison Officer, was secretary/executive officer to the four person senior management group.

When the Assistant Director positions were created, the Assistant Director - Administration and Finance was classified one level below the other two. After some months of operation, the Public Service Board recognised that this was a true executive management group, and reclassified the Assistant Director Administration and Finance to the same level as the others.

Branch heads’ meetings

Irving’s management style, although firm-handed was also very consultative. To ensure on-going interaction between the “operational managers” (Branch Heads) and the executive, he called formal meetings of all parties every three months.

Many items on the agenda related to perceived problems between the branches and the administration, finance and human resources service units and between the Department and the central public service agencies (Public Service Board, Public Buildings Department and the Treasury). The meetings also provided an effective forum for discussion between senior management on all issues affecting the whole Department.

Regional developments

For the first time since a short-lived effort in the South East in 1910 to 1915, (appointment of a Supervisor of Agriculture for the South East, see Early Directors – William Angus 1904–10) an approach to a regional concept in the Department’s work was made with the establishment of a Regional Centre.

The South East Regional Headquarters was located in the old Robinson homestead 'Struan House', just south of Naracoorte and adjoining the Struan Research Centre. This was however more of a centre for service delivery than a regional management structure. Struan was the forerunner for regionalisation and became the South East Regional Headquarters in 1977.

Further information about Struan

In addition, four Regional Research Liaison Committees, comprising departmental officers and representatives of relevant industry organisations, were established with the stated objective of adjusting research and extension programs more closely to the day to day problems of agriculture in their region.

Objective planning for extension programs

A small in size but large in impact development was the appointment in 1970 of Geoff Thomas as Senior Research – Extension Liaison Officer to serve in the South East, based at Naracoorte. Thomas had added a post-graduate Diploma of Agriculture Extension from the University of Melbourne to his Adelaide BAgSc and four years of field experience with the Soil Conservation Branch. His appointment, fostered by Chief Extension Officer, Peter Angove, and funded from CESG, was a pioneering project for the Department. It lasted only three years before Thomas moved to a regional post at Mildura with the Victorian Department of Agriculture.

In a short space of time, using proven features of effective extension work, Thomas laid a solid base for planning of programs targeted to producers’ identified needs. This methodology made full use of the local media, farm visits, field days and demonstrations, and advisory publications. It took extension from a rather hit and miss affair in the region to a planned approach involving more than 50 documented projects. The use of Fact Sheets became the norm, not only increasing the impact of the written word on farmers, but also helping research officers distil information into simple factual messages.

With no regional management structure in place, the participation rate in Thomas’s projects by departmental staff varied considerably. Some sectors and individuals cooperated with enthusiasm while others, especially in animal husbandry and health, tended to remain aloof.

Although Geoff Thomas’s work in the South East was of short duration, it created a considerable awareness of the value and efficiency of extension planning. When the South East became the first operational region under the program commenced by Director Jim McColl in 1977, the ground work established in 1970–73 provided fertile soil for the implementation of a regional management system for all relevant departmental services in the years to come.

Farm management and economics

The need for greater departmental resources in farm management economics to support regional programs was also recognised, and the Agricultural Economics section of the Extension and Information Branch was expanded. Irving also fore-shadowed the raising of Agricultural Economics group to branch status, with direct responsibility to senior management.

Expanding legislative responsibilities

During the period 1970 to 1976, there were more than 60 new Acts or amendments to existing Acts passed that impacted on agricultural industries. This high level of legislative activity included considerable marketing legislation associated with oats, barley, wheat, eggs, potatoes, margarine, dairy and meat industries. There was also considerable legislative activity associated with fruit fly, phylloxera, soil conservation and country fires.

View full list of acts established during this period

Agricultural chemicals legislation

One of the most significant and far-reaching acts introduced was new legislation to manage the registration and use of agricultural chemicals.

Some attempts had been made early in the 20th century, through the Insecticides Act 1919, and Fertilizers Act 1919, to control the labelling and efficiency of agriculture chemicals being sold to South Australian primary producers. Chemical supplements and pest control agents were relatively simple in those times and until the end of WW2. The main emphasis in these early Acts was on “truth in labelling” so that farmers and orchardists could rely on getting the actual minerals or pesticides they were buying, and in the stated quantities.

Experimental Boom sprayer on a Dodge car c 1950.

Growing sophistication of chemicals required new agricultural chemical legislation and establishment of a dedicated agricultural chemicals unit.

A revolution in agricultural chemicals began in the 1940s with the advent of new insecticides like gammexane (Lindane) and DDT. Trace elements were being added to fertilizers, and fungicides differed widely from the long established Bordeaux, lime sulphur, and white oil mixture. New, more sophisticated and selective herbicides also appeared. The complexity and diversity of this whole field continued to grow exponentially and brought with it concerns about off-target damage, problems with residues in soil or produce, environmental damage and the capacity of pests to develop resistance to some treatments.

The Agricultural Chemicals Act 1955 was updated with amendments in 1975, and provided a more comprehensive legal base for government monitoring and control. It operated through registering a chemical for particular uses and providing for such precautionary mechanisms as with-holding periods. Coordination between States and widespread information sharing helped maintain the service.

The SA Department of Agriculture’s ability to effectively manage agricultural chemicals legislation was enhanced by establishing a new position, Principal Agricultural Chemicals Officer. In November 1971, B D (Jim) Robinson was appointed to this position. Robinson was an ideal man for this job, having an agricultural science degree and many years of experience in the agricultural chemicals industry with ICIANZ, based in Victoria. His appointment greatly increased the Department’s capability to provide a highly effective service in this field to farmers and orchardists and to the community at large, the influence of which was felt for many years.

Advice on weed control, pesticide application to all crops, and use of veterinary medicines became a major role for the Department’s growing extension service.

Control of noxious weeds

Control of noxious weeds was an early objective of the Colonial government. Despite numerous attempts over the years to establish a legal framework in which the two elements of local knowledge and central government concern (for state wide issues and possible eradication programs) had not achieved a satisfactory level of success.

During the 1970s, the good work of the Advisory Committee on Noxious Weeds and A.F. Tideman’s weed science section of the Agronomy Branch led to the development of some new concepts. These were embodied in a new Pest Plants Act which came into effect in July 1976.

Brucellosis and tuberculosis eradication

The cattle diseases brucellosis and tuberculosis (BTB) are both readily transmitted to humans in whom they have serious health effects. Since the late 19th century, attempts were made to minimise their impact by testing and certification of freedom from TB in dairy herds, and provision of free Strain 19 vaccine to tackle brucellosis.

With the tightening of import standards by overseas buyers of Australian beef and dairy products in the late 1960s, a concerted effort by Commonwealth and State governments was begun to eradicate both diseases from Australia’s cattle herds. Much debate and negotiation culminated in 1970 with the launch of the Brucellosis and Tuberculosis Eradication Campaign (BTEC), funded by the Commonwealth and State governments with input from the cattle industry.

BTEC, with the funding constantly under review, involved the following measures:

- Legislation to provide for compulsory tail tagging of cattle, compensation for slaughter of reactive cattle, standard definitions and rules, and control of livestock movement.

- Provision of computers for the newly designed Australian National Animal Disease Information System.

- Provision of comprehensive field and laboratory testing services.

- Appropriate extension and publicity programs to ensure understanding of the purpose and procedures of BTEC.

- Negotiation with abattoirs and meat unions re the slaughter of reactors (Brucellosis is easily transmitted to meat workers as undulant fever).

The Department of Agriculture Animal Health Branch, and later, regional operations, were funded for major increases in the number of veterinarians, stock inspectors and clerical staff. Substantial funds were also provided for laboratory staff in the Veterinary Division of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (IMVS), which was later transferred to the Department of Agriculture. Approximately 50 additional field staff and technicians were employed for the program.

The first years of the program focussed on the higher rainfall areas of South Australia. Despite some difficulties and teething problems, good progress was made by the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, attention was focussed on the more difficult pastoral country where large holdings, open range management, and frequent drought conditions made for hard going and slow progress.

The BTEC ran until 1988 when state-wide freedom from brucellosis and tuberculosis was officially declared.

Research management

Attention also focussed on the Department’s research programs, not only by Lex Walker’s appointment as Assistant Director – Research and Extension, but also by the establishment of two committees:

- A Research Policy Committee at branch head level to develop and set criteria for determining research priorities so that, within the limits of available resources, urgent new projects could be undertaken and lower priority work phased out

- A Research Liaison Committee of principal and senior research officers to see that the policies and priorities laid down by the above committee were put into effect and that research projects were well-designed and made the most efficient use of financial, physical and personnel resources.

These two committees, along with the four Regional Research Liaison Committees, signalled a growing recognition of the importance of new technologies to drive productivity improvement, and the need to link research and development to industry. It was also the commencement of fundamental changes to the management and delivery of research and development that occurred during the 1980s and 1990s.

Relationships with government

For the first six months of Irving’s tenure, the Minister of Agriculture was Ross Storey (Liberal) MLC. In June 1970 with re-election of the Dunstan government, Tom Casey MLC was appointed as Minister, and held the position for the next five years. With Casey came (for South Australia) a new phenomenon – the ministerial press secretary. For quite some time, ministerial press secretaries had been used in New South Wales and Victoria where they were much in evidence in the entourage of Ministers of Agriculture at meetings of the Australian Agricultural Council.

It is worth noting that in the days of the Playford Government, not even the Premier had a press secretary. Whenever Tom Playford had a public announcement to make and chose not to reveal it in Parliament, his office would telephone each of the three major media outlets – 'The Advertiser', 'The News' (afternoon daily paper) and the ABC (mainly radio at that time), and their political roundsmen would call on Playford as a group to later report his words.

Marshall Irving addressing guests at Parafield Research Centre with the Premier, the Rt Hon Don Dunstan in 1972.

With the advent of the second Dunstan government, it became clear that there was a firm intent to regularly publicise its plans and achievements and Ministerial press releases soon were established as a very significant part of the public sector scene. At about this time, Dunstan also expressed misgivings concerning the dedication of some elements of the public service in actively supporting the new and at times challenging programs being introduced. His response was the progressive introduction of a new component of the system, ministerial advisers or research officers. These were appointed by the Minister and responsible only to him, operating outside the traditional Departmental framework. Relationships between Ministerial Advisers and the permanently tenured staff of the Departments did not always run smoothly. Shades of “Yes Minister”!

Overseas activities – Libya

For some time Department of Agriculture staff members had used their expertise to assist underdeveloped countries by taking leave without pay to work for international aid agencies (such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) or had been given paid study leave to gain experience in such areas. It was not until 1973 however that the first structured overseas project, agreed at an inter-governmental level appeared.

At this time South Australian agricultural scientists, farmers and agri-businesses had become interested in areas near the north coast of Libya, which has a Mediterranean climate and similar soils to this state. There were opportunities for sale of pasture seeds, agricultural machinery and fencing materials to service a possible transfer of dryland and mixed farming systems. Visits by representatives of South Australian Seedgrowers’ Cooperative (Seedco), Cyclone, John Shearer and Horwood Bagshaw paved the way for closer links with Libya. The work of Senior Seed Production Officer in the Department (David Ragless) during his visit to Libya in 1972, after having provided significant support to Seedco’s highly successful trade exhibit in Teheran, Iran, established personal contact with leading government officials in the field of agriculture there.

Somewhat unexpectedly, this groundwork led to an invitation in 1973 from a Libyan government agency, the Jabel El Akdar Authority, to establish a large demonstration farm at El Marj in Cyrenaica, with a staff of South Australian specialist extension officers to train the Libyan staff. The project was also supported by a number of practising farmers to assist with necessary field operations.

Assistant Director Peter Barrow was given the task of leading this project which was strongly supported by Premier Dunstan, and, despite some opposition (on international political grounds) from the Commonwealth government, quickly went ahead and became very successful. For a detailed account of this and other similar projects in Algeria, Iraq and Jordan in the period 1973 to 1989, refer to “The Medic Fields” by Arthur Tideman, published by SAGRIC International in 1994. Further information is available from The Mc Coll Years 1975–1985.

This was a ground-breaking step for the Department, and over the next decades led to major developments in international agricultural consultancy delivered by SAGRIC International.

Detailed information about the Libya project and the full array of overseas projects

Moving head office – development of the Monarto Concept

The Department’s Adelaide headquarters had been located in Agriculture Building, Gawler Place, since 1950. This converted Simpson’s factory had long been considered sub-standard as office accommodation and, in the later years of Strickland’s directorship a plan to build a new head office at Northfield was formulated. The Government gave its approval in principle, but such major building projects also required the approval of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works before the capital funds could be allocated.

Public Works approval came in early 1971, and architects Cheesman, Doley, Neighbour and Raffin were appointed to undertake the detailed design and preparation of specifications, working in conjunction with the Public Buildings Department. Office space and associated facilities were also to be provided for the Department of Fisheries as part of the project.

The preparatory plans and specifications had been prepared, ready for the tendering process, a massive set of documents. Following the release of figures forecasting substantial growth in Adelaide’s metropolitan population and the election of the Whitlam government, there was a major thrust from Canberra for the development of new regional growth centres outside of existing State capitals. The suggested availability of significant Commonwealth funding for such projects led the South Australian Government to seek to develop a new population centre at Monarto, just to the west of Murray Bridge, and some 80 kilometres from Adelaide. Part of this proposal was to relocate the almost ready-to-build Department of Agriculture facilities to Monarto.

The 5 story Agriculture Building (centre) on the west side of Gawler Place in 1952.

It was the Department of Agriculture’s head office until the move to 25 Grenfell Street in 1976.

Source: State Library of SA File B12359.

The Monarto proposal caused a major upheaval within the State’s public service, especially in the departments directly affected. The Public Service Board appointed a consultative committee under the chairmanship of one of its commissioners (Iris Stevens) with representatives of the Departments concerned and the Public Service Association.

This consultative committee worked with the Monarto Development Commission (which had been set up to plan and oversee the development and building of Monarto) to thrash out the terms and conditions under which the substantial number of public servants would be transferred out of metropolitan Adelaide. Not only was there a natural reluctance for departmental officers to face moving their homes from Adelaide or, alternatively, commuting about 150 kilometres daily to and from Monarto, but many other questions arose and were debated, such as possible compensation or other forms of assistance, and how much “compulsion” would be involved. An operational concern for the Department of Agriculture was the difficulties likely to arise for technical and other staff to access day-release training at tertiary institutions.

These problems disappeared when revised population estimates showed that the proposal for Monarto could not be justified in the immediate future. The defeat of the Whitlam government in December 1975 took the political wind out of the Monarto sails as well. The land acquired at Monarto for the new city benefited by the extensive tree-plantings which had occurred. A significant area of this land was used for development of a world-class free-range zoo. Much of the land was also sold back to farmers.

The Black Stump – a new Grenfell Centre head office

With the realisation that Monarto would not go ahead, the Government also recognised that something had to be done about the highly unsatisfactory Agriculture Building. Leasing of six floors of the AMP Society’s new office block at 25 Grenfell Street, commonly known as the “Black Stump” (because of its external cladding with black glass panels) was arranged. Previously planned office layouts for Northfield were of little value. After a frenzied period of planning and design work, a layout was developed for the 13th to 18th floors to accommodate the Department’s head office staff along with the Minister of Agriculture’s Department, using a mixture of open plan and enclosed offices.

Included was a combined Departmental inquiry office and home gardens advisory service adjacent to the entry lobby on the ground floor. Specialist facilities like the Seed Testing Laboratory, audio and visual aids work areas, and excellent conference and meeting rooms were provided for. The timber décor along with new modern furniture and fittings, helped give a pleasant feeling of light and air throughout.

The Department abandoned its run-down accommodation in Agriculture Building (and several other locations leased when the Gawler Place building became fully occupied) and moved with some pleasure into the Black Stump in the first half of 1976.

Enquiries, enquiries, enquiries

For several years from July 1971, there was a continuous series of enquiries into and re-evaluations of the Department of Agriculture. In the latter part of this period, the Department was also caught up in the broader issues canvassed by Professor David Corbett’s wide-ranging “Committee of Enquiry into the Public Service of South Australia” which ran from 1973 to 1975.

Statement of aims and objectives

On 4 July 1971 a request came from the Premier for the Director of Agriculture to provide Cabinet with a clear statement of the aims and objectives of his Department. These had not previously been formally defined. Marshall Irving took the request as a personal challenge and devoted himself virtually full-time to the task, with the support of Scientific Liaison Officer Viv Lohmeyer. He left day- to- day management of the Department to his three Assistant Directors, while keeping himself regularly informed of significant issues as they arose and dealing with policy matters at the “top level”.

Within six months he produced a ten page document comprising six sections:

- Objectives of the Department

- The Problems of Agricultural Industries

- Role of the Department of Agriculture

- Staffing

- Finance

- Conclusions

“The Objectives of the Department of Agriculture” was submitted to the Government at the end of 1971 and its statements accepted, but a further report was requested (to be made to the Public Service Board) setting out the Director’s assessment of the future role of the Department.

Once again, Irving took the issue in a quite personal way and vowed to address the matter accordingly. With the constant support of Viv Lohmeyer and after consultation with the Assistant Directors, he submitted his report to the Board, through the Minister of Agriculture, on 30 June 1972.

There is no doubt that Irving found the whole of the previous 12 months very stressful and from the latter part of 1972 was forced to take periods of sick leave because of chronic high blood pressure which could not be well controlled by the medical therapies available at the time.

A key feature of Irving’s submission was to point out that the proportion of the State budget of South Australia devoted to agriculture at 0.9% was less than half the proportion in the five other States which averaged almost 2%, ranging from 1.6% in Western Australia to 3.2% in Tasmania. The report also included an organisation chart of the Department as it was in 1971.

Complete Irving reports including organisational chart of the agency at that time

Irving’s report began with a review of the current scope of Departmental activities followed by the development of its major thrust. After an introductory section, high-lighting the changing pressures on farming of numerous interacting factors (marketing and quality issues; productivity and assimilation of new technologies;

social, economic and environmental concerns), Irving spells out his vision for the ways in which the department should tackle the challenges, under the following headings:

- Regulatory activities

- Economics and marketing

- Extension services

- Research

- Industry liaison

- Agriculture and the environment

- Administration

- Resources needed

Irving’s proposals were subsequently used by A R Callaghan in his “A Review of the Department of Agriculture in the light of Changed and Changing Needs”. They can be found in Appendix 3 of this Callaghan report and can be accessed through Reference Material/Reports.

Of special interest in the context of this history of the organisational development of the Department are:

- Irving’s reference in his section on Regulatory Activities to the advantages of having “certain technical services at present located in other Departments transferred to the Department of Agriculture to provide more effective administration of these activities”. He refers in particular to the export grain inspection service provided by the Government Produce Department (as agent of the Commonwealth government), the Vermin Branch of the Department of Lands (in regard to rabbit and other pest animal control), and the Veterinary Division of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (in regard to veterinary diagnostic and animal disease research services). It is noteworthy that all three of these services were transferred to the Department of Agriculture within a decade.

- Under the heading “Resources Needed”, Irving stated that “The Department’s research and advisory services will need to be regionalised”. He does not, however spell out the way in which regionalisation should be achieved nor did he envisage the regional management of regulatory services.

Allan Callaghan’s review

The Irving report on the Department’s future role, having been submitted to the Public Service Board, did not bring an immediate response. The SA Government, however, decided to ask Sir Allan Callaghan to review Irving’s reports and make recommendations for future action. Callaghan, a former Director of Agriculture (1949–59), had recently retired as Chairman of the Australian Wheat Board, and returned to Adelaide to live.

Callaghan was provided with an office and a secretary and funded for considerable travel which enabled him to have valuable contact with the operations of the New South Wales and Victorian Departments of Agriculture (which had significant experience with regional operations) and with relevant Commonwealth agencies in Canberra. He also consulted widely within South Australia, both in person and in writing, covering all elements of the Department of Agriculture and the representatives of many producer organisations.

He worked on the review during the second half of 1973 and submitted his report in December of that year. It is entitled A Review of the Department of Agriculture in the Light of Changed and Changing Needs.

The main thrust of Callaghan’s recommendations was to place the activities of all front line service delivery staff – whether engaged in research, extension or regulation – under the management of five regional directors who would interact with seven head office-based Divisional Chiefs, for the following units:

- Economics, Marketing and Farm Management;

- Information and Public Relations;

- Plant and Animal Industries;

- Regional Centre Control;

- Central Research Laboratories;

- Policy Co-ordination and Development; and

- Staff Development and Management Services.

Callaghan also strongly recommended the creation of the position of Deputy Director, not to interpose another level of authority between the departmental head and the next senior management group, but to be what he called “a true deputy”, sharing the director’s responsibilities, especially to free him to concentrate on the issues of widest importance and on policy matters.

Callaghan’s report was well received and became a key reference point in the development and implementation of the major departmental organisational changes which began in 1977.

Corbett’s committee of enquiry

Dunstan’s government was ever on the alert to re-evaluate activities and policies and to introduce changes which had far-reaching impacts on South Australian society and the provision of public services. A major component of this continuing process was the establishment in 1973 (under the chairmanship of Canadian-born foundation Professor of Political Theory and Institutions at Flinders University, David Corbett) of A Committee of Enquiry into the State Public Service.

It ran until 1975 and canvassed a wide range of issues affecting the structure and operation of the whole service. Major thrusts were to reduce the number of SA government departments (which by uncoordinated evolution had grown to more than 50, with some of them having only a handful of staff) and at the same time to look at more effective groupings of functions within single Departments.

This ground-breaking enquiry had two effects on the Department of Agriculture:

- Cabinet decided not to fill any vacant Permanent Head positions until the outcome of Corbett’s enquiry was determined. Because of Irving’s continuing illness and sick leave, the Department was without an appointed director until July 1976, causing a great deal of uncertainty amongst staff and rural industries.

- After Corbett’s report started to be implemented, additional agencies were brought into the Department including one of the three identified in Irving’s second report, (vermin control) plus administration of Rural Assistance programs, both transferred from the Department of Lands.

Coping with uncertainty

During the early stages of Irving’s illness, when he was able to return to duty for a time after each period of sick leave, Lex Walker became Acting Director. Later, as Irving’s condition deteriorated and it seemed unlikely that he would ever be able to resume his duties, each of the three Assistant Directors held the position of Acting Director at different times.

The Public Service Board recognised that this was a highly unsatisfactory situation, but was prevented from taking definitive action by the Government’s embargo on filling vacant permanent head positions. This was overcome in part, by adopting one of Callaghan’s recommendations, and in September 1974 the new post of Deputy Director was created.

In March 1975, Peter Trumble was appointed Deputy Director and continued as Acting Director (apart from periods of leave), until Irving’s successor took up duty in July 1976. Marshall Irving’s short tenure of the directorship came to an end on 11 February 1975 when he was forced to retire because of ill health.

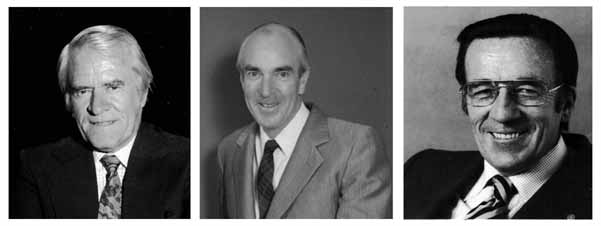

Left to right, Acting Directors Lex Walker, Peter Barrow and Peter Trumble who shared the role of Acting Director during the numerous periods of Marshall Irving’s sick leave and following his retirement.

This brought some stability to the senior management of the Department, which was further strengthened with the appointment of H C Matthews, to fill the now vacant position of Assistant Director – Administration and Finance.

Other departmental developments

In the period of seemingly endless reviews coupled with temporary appointments at top management level, it is not surprising that the Department was very much in a holding pattern. Its leaders and staff followed the programs of work flowing from Irving’s initial three years, maintaining quality research, extension and regulatory services aimed at improving farm and orchard productivity and efficiency or enforcing the manifold requirements of legislation entrusted to it. There were, however, a couple of significant changes at this time:

Table margarine production quotas

From the earliest years of the Australian Agricultural Council, State Ministers of Agriculture had fought a continuing battle on behalf of Australian dairy farmers to limit encroachment by table margarine into domestic markets for butter. This was done in two ways. Firstly, the colouring of table margarine was restricted to minimise its ability to look like butter. One Minister famously said that if he had his way, all table margarine would be coloured black! Secondly and principally, by the imposition under each State’s law of a quota for the production of table margarine, enforced by regular inspections of all margarine factories.

These laws had become increasingly more difficult to justify as margarine quality improved, more and more Australian-produced vegetable oil was being used (rather than “imported oil grown by cheap foreign labour”) and the health benefits of unsaturated vegetable oils over animal fat became more widely recognised. In one of his last actions as Minister of Agriculture, Casey announced to the Agriculture Council without prior notice that South Australia was to repeal its margarine quotas legislation. This quickly triggered the abandonment of margarine legislation by all states.

Agricultural Economics Branch

In May 1975, Trumble secured Public Service Board approval to separate the Agricultural Economics Section from the Extension Services and Information Branch. This created a new branch, directly responsible to the executive under the now designated Chief Agricultural Economist, Colin Hunt. This development had earlier been foreshadowed by Irving in 1972.

Export grain and flour inspection

Ever since the Commonwealth took over responsibilities for oversight of Australian export trade in the early 1900s, the South Australian Government Produce Department had acted as its agent for the inspection of grain and flour exports from the state’s ports to ensure that international trade standards were met. In 1971–72, a working party under the chairmanship of J.R. Dunsford was set up to review the operations of the Government Produce Department. It reported in March 1972, and, among other matters, recommended that its grain inspection functions be transferred to the Department of Agriculture.

This recommendation was accepted, and over the next three years, the necessary administration and industrial arrangements were made, enabling the transfer of the export grain inspection services (comprising 12 officers employed under the Public Service Act and approximately 24 casual staff seasonally employed through the Associated Employers and Waterside Labourers - AEWL) to the Department of Agriculture. This occurred by September 1975.

The technical and inter-government issues involved in the transfer presented few problems as they were similar to those in place for export inspections of fruit and other plant materials. Industrial problems were a potential issue because of the special employment arrangements which were in force to cater for dock side and on ship inspections at the seven grain exporting ports from Pt Adelaide to Thevenard.

The nature of ship loading operations required longer shifts than usual, with significant overtime payments, a good deal of travelling, and the employment of local casual staff to meet seasonal demand. There were also occupational health issues arising from risks to staff required to work in enclosed spaces and the hazardous materials used in treating grain.

Deeply entrenched industrial arrangements required that all casual staff employed be hired through the AEWL. These employees were required to be members of the Federated Clerks Union. This caused the Department of Agriculture to become involved in an unfamiliar industrial relations environment.

All of these complications were worked through with the involvement of the Public Service Board and all the other agencies concerned. The export grain inspection operations were eventually smoothly integrated with kindred inspection services already operating in the Department.

Meat hygiene

While the need for proper hygienic practices in the slaughter of animals for meat and the subsequent handling of meat products had been recognised for centuries, effective implementation of such practices were slow to develop. Initially seen in South Australia and elsewhere as an appropriate responsibility of local government, this was not formalised until the Metropolitan Abattoirs Act 1905 and the Abattoirs Act 1911 respectively provided a legal framework for a central meat works at Gepps Cross and authority for municipalities to establish an abattoir with a certified meat inspection service.

To this core of regulated abattoirs, a range of other meat works developed in rural areas using state inspection services (eg Adelaide Hills bacon factories). In many rural areas, slaughterhouses operated by local butchers were supervised by the local boards of health using district council inspectors.

With increasing insistence on higher quality and hygienic procedures by world markets and changes in the structure of the meat industry in the 1970s, there was a growing desire in the community to better organise and improve the standards of Australia’s meat inspection arrangements. This led to the drafting in 1975 of a Meat Industry Bill covering all aspects of the industry from slaughtering to marketing, but in light of the uncertainty of the viability of SAMCOR at Gepps Cross, was shelved by the SA Government.

There the matter rested until the issue resurfaced a few years later and eventually led to the passing of the Meat Hygiene Act 1980 (further information is contained in The Mc Coll Years 1975–1985).

Information about current meat hygiene management (PIRSA website)

The advent of the Animal Health Advisor

Field services aimed at the control or eradication of stock diseases began in the 1860s and were amongst the earliest attempts by South Australian governments to offer services to farming industries. From 1936, research and diagnostic services were being provided by the Veterinary Science Division of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science.

Animal health services evolved continuously, and by the 1970s the Department of Agriculture employed qualified veterinarians, backed by field based stock inspectors who often did not have tertiary qualifications.

It was recognised that the work of the stock inspectors could be enhanced by using the legal, enforceable powers provided by the Stock Diseases Act in an extension and advisory framework. This approach came into effect in 1973 with the creation of positions entitled “Animal Health Advisors” which enabled existing stock inspectors who had a Diploma of Agriculture and a proven ability to communicate effectively as extension officers, to be recognised and reclassified to this more professional level.

This system became the norm and the officers working in the field were encouraged to approach stock disease problems in an educational and advisory way. Their powers as inspectors under the Stock Diseases Act were kept in reserve, to be invoked where necessary to deal with emergency situations or where stock owners proved unresponsive to advice.

A Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

In mid 1975, the Chairman of the Public Service Board informed the Acting Director of Agriculture (H P C Trumble) and the Director of Fisheries (A M Olsen) that for a number of reasons, the government was considering amalgamation of the two Departments. As a result, the fisheries unit would lose its departmental status. He invited their comments. While Olsen was naturally unenthusiastic about the proposal, both he and Trumble noted that such a combination operated successfully in other parts of the world, and agreed that if that was what the government wanted, it was workable.

On 15 October 1975, under the Public Service Act, the Fisheries Department and all its officers were transferred to the Department of Agriculture, to be known as the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Trumble, as acting head of the combination was gazetted as Director of Fisheries under the Fisheries Act 1971.

In making the transfer of the fisheries function, the Public Service Board made it clear that the management of fisheries research was to be separated from the processes of enforcement of the Fisheries Act. This meant that there was a Fisheries Research Branch, headed by former Director of Fisheries Olsen, and that the licensing and enforcement operations were placed under the control of Chief Administrative Officer Harry Shaw. The legal powers stemming from the Fisheries Act sat with Acting Director Trumble who had an extensive capacity to delegate them to licensing staff and inspectors.

This amalgamation had little effect on the agricultural operations of the department but it brought a totally new and intensive work load for Trumble and Shaw.

The Fisheries Act 1971 gave enormous powers to the Director (and sometimes the Minister) to control, regulate, limit or ban the whole range of fishing operations. The Act was supported by an extensive body of regulations, proclamations, statement of government policies and ministerial permits (which allowed for certain permits such as exploratory or research fishing). Much of the detail was in the regulations and proclamations which were constantly under review for legality by Crown Law solicitors in the face of frequent questioning by fishermen. Fishermen aggrieved by a decision of the Director could also appeal to a tribunal comprising a magistrate (experienced in fishing and nautical matters) and before which the Director or his delegate had to justify his decision.

At the time, a Fisheries Policy Committee operated under the chairmanship of Bruce Guerin. Senior Policy Advisor with the Premier’s Department. It was considering broader questions of fisheries policy including the owner-operator licensing system versus corporate ownership, and optimising fishermen’s income while sustainably managing the fisheries resource. It used international experts on fisheries management, such as Professor Parzival Copes of Simon Frazer University, British Columbia.

Constant communication was needed with fishing and fish processing organisations. These were loosely represented by the Australian Fishing Industry Council – S.A. Branch (AFICSA) which also collaborated with the Department in the publication of a highly informative quarterly magazine called “SAFIC”, supplied to all licensed fishermen.

A new style of Minister

In March 1975, Minister Tom Casey went overseas (including a visit to Libya). For three months Deputy Premier Des Corcoran was Acting Minister. In June 1975, Brian A Chatterton MLC was formally appointed Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Forests and Minister of Fisheries.

Chatterton was elected as a Labor Party member of the Legislative Council in 1973 and had established himself as an active proponent of change in the state’s agricultural services. He had many ideas about ways to improve the delivery of agricultural services in South Australia and had voiced them vigorously for some time in a wide range of forums.

Brian Chatterton had a farming and wine making background in the Barossa Valley and also held a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture degree from Reading University, U.K., having majored in farm management economics.

His close involvement with day to day matters within the Department came as something of a shock to many officers who were used to a rather more distant albeit cordial, relationship with their ministerial head. He quite often took the initiative in establishing direct contact with individual officers with whom he felt rapport or were in areas of special interest to him.

The Department’s programs 1975–76

1975–76 was a year of great change throughout the SA Public Service. Corbett’s recommendations were being discussed and in some areas implemented. Issues like industrial democracy, equal opportunity and staff development were being promoted by the government in all Departments. These did not have a great impact on the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries which already had a well developed and effective program of staff development, especially for its core work force of scientific and technical officers. Extension of this to administrative and clerical staff where needed caused no difficulties.

There were very few females either within the Department or the general community qualified for jobs in agriculture and available for recruitment. Promotion of females into management, service or administrative roles occurred from time to time without upheaval.

Brian Chatterton had a special interest in the communication area and a number of developments took place early in his first term of office. These included:

- The establishment of a Home Gardens Advisory Service within the Extension Branch, embracing the work previously provided by the Horticulture Branch and adding a general reception and information service for the whole of Head Office.

- A major development was the publication of fact sheets on specific topics, as the principal printed medium for conveying advice to producers and other clients. Chatterton believed that too much reliance was being placed on the “S.A. Journal of Agriculture” which had grown up primarily as the information organ of the Agricultural Bureau system. He felt that fact sheets, produced for particular purposes or to address specific topical problems were a more effective medium and required the department to given this area high priority.

- Brian Chatterton had a long established interest in the potential transfer of Australian dry land farming systems to other countries with a Mediterranean climate. He quickly involved himself in aspects of the Department’s project in Libya and its wider implications. This led to the publication of a high quality book entitled “Farming Systems in South Australia”, written by departmental officers Glyn Webber, Phillip Cocks and Brian Jefferies. It was also published in French, Arabic and Chinese, and was launched by Premier Don Dunstan in a public ceremony at the Northfield Research Centre in early 1976.

The waiting time

By early 1976 it was clear that an appointment to the vacant directorship of the Department would not be too far away. Brian Chatterton had been in office over six months and had formulated what he would be seeking in a new Director. The implications of Corbett’s recommendations were becoming clearer and the Fisheries element of the enlarged Department was settling down.

Every one recognised that the new Minister would have strong views on what style of Director the Department needed. The position was widely advertised in February 1976, and there was much speculation as to whether an external appointment, possibly from outside South Australia, would be made, or an existing officer of the Department would be selected.

In June 1976, it was announced that the new Director of Agriculture and Fisheries, to take office from 1 July, would be James C McColl. At the time he was a senior lecturer in farm management with the School of Agriculture of Melbourne University and a private agricultural consultant.

So an end came to the often debilitating uncertainty and with that, an opportunity for the Department to move forward positively and with confidence into the future.

The author

This article was researched and written by Peter Trumble, retired Deputy Director General of the Department of Agriculture.

Postscript

This point in the history of the SA Department of Agriculture as an organisation marks the end of my involvement in it as a sole author. The period from 1976 to 1992 is covered by Don Plowman, with myself as junior co-author for the McColl Era chapter. This is therefore an appropriate time in the record to briefly summarise how the project began and how I went about it, the list the written sources I drew on, and to acknowledge those who I found especially helpful.

The history of the history

The idea of this publication arose around 2009 when, at Arthur Tideman's invitation I attended a few meetings of the History Group with a view to helping with their great work. After I got the hang of what they were doing, I asked if a history of the department, from its embryonic stages in the first half of the 20th century until the end of the Jim McColl's term as Director-General, would be of interest. I suddenly found I had made an offer that was accepted on the spot.

Getting started

The first thing to do was to identify appropriate sources. My memory of close involvement with and/or interest in the department from July 1950 to January 1983, followed by a few years of tapering off, part time contact, was of course the primary source. This was supplemented by study of the annual reports to parliament by the Minister of Agriculture from the early 1900s to about 1975 and reference to a number of other documents listed below. It all seemed to fall into place quite quickly and was assisted by much information provided by discussions with many people, the principal ones whom are acknowledged below.

Other sources

The unpublished work of former State Archivist, John Love, served me well in finding a path through the haphazard, intermittent attempts to devise and develop government services to SA's farmers in the 19th and first decade of the 20th century. Building on the landmark reports of the Royal Commissions of 1867 and 1875, under the strong political influence of Richard Butler (arguably the first "real" Minister of Agriculture), William Angus, between 1903 and 1991, was able to get together a service unit which looked a wee bit like a present-day Department of Agriculture.

Other main published sources were:

- The Wheat Industry in Australia by AR Callaghan and AJ Millington (Angas and Robertson 1956)

- The First Fifty Years, 1924–1974 by VA Edgeloe (Waite Agricultural Research Institute, 1984)

- A Century of Service edited by J Daniels (Roseworthy Agricultural College, 1983)

- The Medic Fields by AF Tideman (SAGRIC International, 1994)

- Allan Callaghan - A Life by Ross Humphries (Melbourne University Press, 2002)

- The Waite by Lynette Zeitz (Barr Smith Press, 2014)

Acknowledgements

A great number of informal chats with former colleagues over the years have helped me remember or put into better focus past events in the Department.

In addition to these I wish to record my gratitude to a number of people for their particular and highly valued support they supplied willingly;

- Tony Davidson (meat hygiene and the BTB program)

- Trevor Roberts (information about the infrastructure and facilities at a number of research and other centres)

- Frances Edwards (details of the operation of the Departmental library)

- Don Harvey (some details on the operations of the BTB program)

- Geoff Thomas (extension planning and management)

- Arthur Tideman (Weed control and the 1955 locust campaign)

- Tricia Fraser (Secretary to the History Group)

- The girls in the Woolhouse Library at the Waite Institute who facilitated access to that library's holdings and sometimes let me borrow special titles.

- Rosemary Hawke (Secretary to Don Plowman) who did a brilliant job, so cheerfully and willingly in translating my almost illegible hand-written material to a perfectly typed manuscript.

I also greatly valued the continuing general support given by Arthur Tideman, Don Plowman and John Radcliffe and the opportunity to talk to Jim McColl in the latter stages of his terminal illness, reviewing our time together in 1976–83.

But the man who helped me most was Barry Philp, a member of the History Group. His wide knowledge of the Department, ability to use IT to access an incredible array of sources, enthusiasm for the task, and willingness to be a cheerful sounding board off which to bounce ideas, made possible the completion of the task I could never have done alone.

Prepared by: Peter Trumble

Date: December 2018