Eradication

Eradication is the destruction of all flies and larvae within the outbreak area. For quarantine purposes, eradication is defined as when no flies or larvae are detected within that area for a period equivalent to three fly generations. Under local conditions in summer in Adelaide, that period is 12 weeks, but this is longer in cooler seasons.

The operating model for fruit fly eradication in South Australia is of repeated introductions of fruit fly into South Australia from outside the state; these are detected, usually before they produce a second generation, and are eradicated. The evidence from numbers of flies caught in traps, and larvae found in out break areas suggests that the number of flies in each outbreak does not total more than several hundred.

It is likely that both Medfly and Qfly, left uncontrolled, could survive in many South Australian areas, including Adelaide.

A comprehensive analysis of the South Australian outbreaks was done by Derek Maelzer on data up to 1987. Maelzer concluded that the pattern of outbreaks was consistent with repeated introductions. Certainly, the data from roadblock interceptions indicates a mechanism by which regular introductions could occur.

Management of detection, eradication and general operations associated with fruit flies in South Australia is covered in the Pest Eradication Unit’s Operational Manual, which is revised annually. Operations associated with eradication in a commercial orchard district are covered in the Fruit Fly Contingency Plan – Riverland, also revised annually.

From 1947, the first action taken after an outbreak was proclaimed was to search for larvae in fruit in the suspect area, to determine the extent of the outbreak. Fruit in all properties within a half mile radius of the original sighting, was examined for larvae of fruit fly. These early checks involved large numbers of staff from the Department of Agriculture1 including those from country areas, as it was considered important to determine the extent of the outbreak as quickly as possible. By 1971 the procedure for eradicating outbreaks included stripping of all host fruit in the area of one quarter mile radius of the outbreak centre, cover spraying the area within a half-mile radius of the outbreak centre, baiting of the entire area and placing of lure pads between the half mile and the outer perimeter. Baits of protein hydrolysate 10 oz (283.5g); maldison 9 oz (255g); Water 3 gals (13.6L) were squirted onto one or more trees in each house yard.

From 1975, less emphasis has been placed on intensive checking and more emphasis placed the prompt establishment of a baiting program, particularly in the outbreak zone. Technical checking and fruit stripping were labour-intensive and stripping of fruit from trees had little biological support.

Baiting

Baiting, to kill adult flies, has been an important part of the eradication program but, until the early 1970s, was not considered as important as the killing and removal of larvae. The bait used in 1947 was brown sugar and tartar emetic (antimony potassium tartrate), the first as a food lure and the second as a stomach poison.

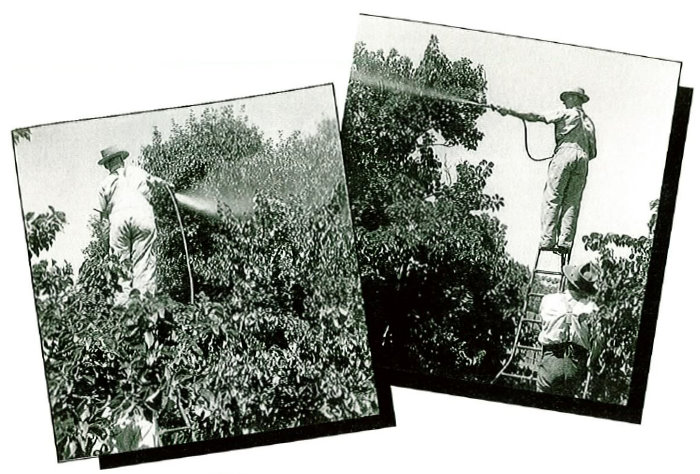

The bait was applied using a knapsack, at the rate of 6 fl oz per ‘spot’ every 7 days. The sprayers were instructed to apply bait to all trees with fruit or berries that looked as if they may attract a fruit fly, and all ornamental shrubs. Baiting remained on a weekly basis and continued throughout winter until the 31st of October. There were no reports of phytotoxity. This technique minimised danger of contact by householders and other non-target organisms.

After a conference on Fruit Fly, conducted by the Department in 1957, the tartar emetic sugar bait was replaced by a by a protein-insecticide bait, based on the developments of a new attractant method by Dr. L.F. Steiner (USDA) in the early 1950s. In 1962, the bait was altered to a protein hydrolysate/ maldison/sugar/water mixture, and was applied weekly until the end of October within the outbreak area and in the following year the bait was modified to: protein hydrolysate 21.9% 170g; maldison 255 grams active constituent formulated as a wettable powder l42g; Water 4 gal (15.14L).

Baiting and cover sprays

Protein from yeasts is attractive to fruit flies and the females, in particular, need to feed on yeasts naturally occurring on plant surfaces to enable them to produce eggs. In the early days of baiting, a protein produced from flour was used, but it had a high salt content and tended to be phytotoxic. Protein hydrolysate produced from brewers yeast as a by-product of beer-making is very attractive to fruit flies. Protein autolysate, made by a slightly different process, is presently used because of its low salt content. The bait attracts both male and female flies from many metres away.

Cover sprays are insecticides applied to foliage and fruit, which kill adult flies by direct contact or by residual action. Cover sprays may also be applied to the ground beneath trees to kill adults as they emerge from the soil. The insecticide may also be absorbed into fruit, and kill developing eggs and larvae.

Improvements to baiting techniques

Dr Alan Bateman, CSIRO Division of Entomology in New South Wales trials found that about 20 bait spots applied at equal spacings over an acre of vegetation killed most adult Qflies in the area, most of them within a few hours following the application of the bait. In 1972, Bateman’s spot-baiting method (each bait spot containing protein hydrolysate 4gm; maldison 1g active in 100mL water) was introduced to South Australia.

On the 4 January 1974, these eradication procedures were used for the first time on an outbreak of Medfly at Kent Town. Other Medfly outbreaks had occurred in the same year in the metropolitan area. There appeared to be a failure in the bait spraying technique and a meeting was held on the 13–14 February to discuss the problem.

Attending that meeting were Horticultural Branch staff associated with the program and entomologists from the Waite Institute, Roseworthy College, West Australian Department of Agriculture and the CSIRO Division of Entomology. During the discussions, Alan Bateman found that the bait mixture was wrongly mixed, and the concentrations of materials that were used in were inadequate to attract and kill fruit flies; only 1/10th of the necessary protein and 1/2 of the necessary maldison were being applied. At the time, the bait used was: Protein hydrolysate 21% 56g actual instead of 620g; Maldison 25% 70g actual instead of 154g; Water 13.2L.

The failure of baiting to achieve eradication was not a fault in the technique itself, but was a result of the low rates of materials used in the bait mixture. It was also noted that the formulation had been tried against QfIy, but not Medfly, the latter being more difficult to eradicate by baiting. A correctly mixed test batch was checked for phtytotoxicity in an abandoned garden with disastrous results; most trees and shrubs showed extensive salt damage within 72 hours. Following discussions with Sanatorium Health Foods in Western Australia, a suitable protein autolysate was produced with three times the concentration of the (acid) hydrolysate but only one third of the salt (NaCl) content and the cost was the same by weight. The first baiting of a commercial orchard using low—salt, high protein formulation was used in 1974 when larvae were found in peaches in a suburban backyard on 5 March and in a nearby plum orchard on 7 March.

By March 1974, baiting was integrated with coverspraying using fenthion within a 1/4 mile radius of the centre of the outbreak, associated with the removal of windfalls and ripe fruit within a 1/8 mile radius. Later in the year, officers of the Horticulture Branch decided that a further investigation of the baiting approach should be made, and that baiting should be the technique used to eradicate any outbreaks during the 1974–75 season.

Formation of Fruit Fly Technical Committee

Following on from the meeting on fruit fly held in February 1974, a group of senior Department of Agriculture officers associated with the detection and eradication of fruit fly was organised to supervise operations. On 12 September 1974, senior Departmental staff met to review the 1973–74 program and to discuss proposals for 1974-75. At that meeting, a Technical Committee called the Fruit Fly Technical Committee was formed to undertake responsibility for the technical aspects of detection and eradication programs. The Committee consisted of the Chief Horticulturist and Chair (Tom Miller), Principal Horticultural Officer (Bill Harris), Officer-in-Charge of the Pest Eradication Unit (Jack Botham) and the Senior Entomologist (Paul Madge). The Committee met again on 11 November and 2 and 19 December, 1974. At these meetings an eradication program for 1974–75 was prepared. The protocol developed for treating an outbreak was recognised by the Committee as a substantial ‘overkill’ and that eradication should consist of distribution of notices to householders; prohibition of the removal of fruit from the outbreak area, concurrent with prompt and intensive bait spraying, and prompt removal of fallen fruit in the outbreak zone.

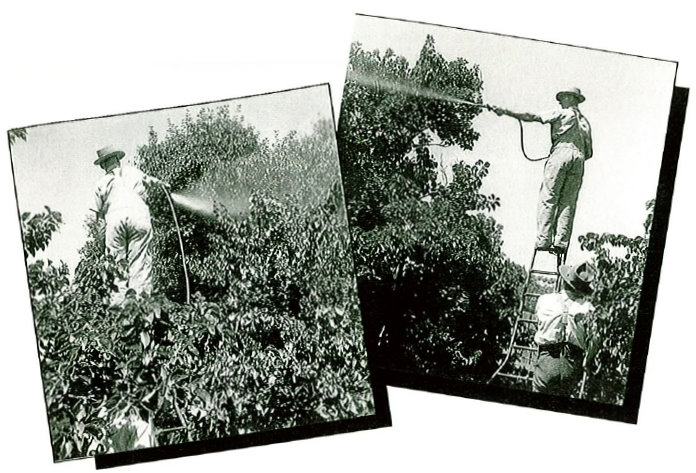

The baiting program consisted of two baiting teams sent to the outbreak zone to begin spot-spraying, all trees and tall shrubs with the protein—maldison bait, but avoiding those likely to be damaged by the spray. Spot-spraying in the outbreak zone is done twice weekly for six weeks, then weekly as in the remainder of the outbreak area. The bait now consisted of: protein autolysate 420g/L protein + 1L; maldison 5% 142mL in 16 L water. Technical maldison with a minimum quantity of formulating solvent was used, as the solvent acted as a repellent to the fruit fly; but some was necessary to enable technical maldison to be mixed with water. Baiting in the remainder of the outbreak area starts at the perimeter moves towards the boundary of the outbreak zone, applying bait at the rate of at least 100 ‘spots’ per hectare once a week. Baiting continues for 9–12 weeks (depending on temperatures and extent of the outbreak) after the last fly or larva is found in the quarantine area.

Further improvements to baiting techniques

Until 1977, baiting teams travelled in privately hired vans with the driver employed by the owner of the van. Teams consisted of a ganger and six sprayers who worked in pairs. One sprayer carried a knapsack containing the bait mixture and applied the bait to trees and shrubs in front and rear yards of household properties, while the other carried additional protein and insecticide and assisted his colleague. When the knapsack was empty, it was filled with water (17 litres) in the street and the protein and insecticide was added from the pre-measured bottles carried. By 1978, government cars were used to tow departmental and hired trailers that carried the necessary equipment. The baiting teams were reduced to a ganger who drove the vehicle and supervised four sprayers who worked in pairs. About 170 properties were baited each day by each pair of sprayers.

In an attempt at quality control, mixing was done at a central point where bait preparation and application could be better supervised. The concentration of bait in the knapsack was checked at random by the Inspector in charge, using a hydrometer. The specific gravity reading was to be 1015 and the checks showed that the bait settled in the knapsack, especially if left standing after preparation. In spite of these precautions, it was discovered in July 1981 that the bait mixture was not correct. In a knapsack with 16 litres of water, the protein was reduced from 1 litre to 850 mL, and the maldison-Hymal® was increased from 142 mL to 147 mL.

In 1982, Bert Hayter, Officer-in Charge, and Nick Perepelicia, supervisor, introduced a procedure in which a pre-mixed bait was carried in bulk tanks on Departmental trailers. These tanks contained 110 litres and were filled 2 or 3 times a day under the supervision of a Departmental Inspector. The bait was kept mixed by a constant—running electric pump. This procedure not only resulted in a more strict control of the preparation of bait (supervised by an Eradication Supervisor) but also resulted in the reduction in costs by reducing the size of the baiting team from five to three. The advantages of this system over the previous was that it maintained a uniform and accurate mixture of bait, reduced costs by eliminating the need for a sprayer to carry refill bottles of protein and insecticide; a team now consisted of a gauger and 2 sprayers. Each sprayer need only carry in the knapsack, the actual quantity of bait required and hence reduce the workload, more properties could be baited each day by each sprayer and it was not necessary to rely on householders to supply water.

Hydrometer tests were gradually eliminated as the mixing of bait became better supervised. As a further move towards greater efficiency trailers with 400 litre bulk tanks for bait (a full day’s supply) were introduced in 1983. The bait was prepared in the morning and kept agitated during the day. The bait mixture has not been altered since corrections were made in 1982. To make 20 litres of bait, the quantities are: low salt protein autolysate 1L; Maldison 115WV Hymal® 174ml; Water 18.826L. The bait is applied in 100 mL spots to 6-8 fruit trees, shady trees or shrubs in each house yard or 100 spots per hectare.

Cover spraying

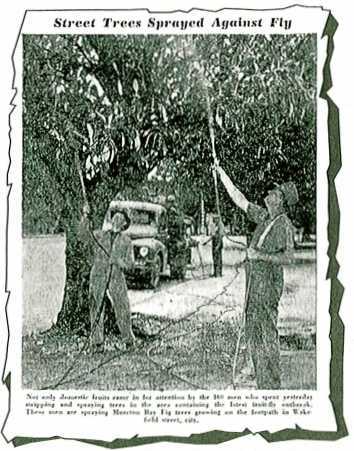

Cover spraying to kill adults sheltering on foliage, was used extensively during early eradication campaigns. A sweetened tartar emetic spray was used during 1947 and was replaced by DDT in 1948. Fruit trees near the outbreak centre of infestations were sprayed thoroughly with 0.1% DDT (2lbs of 50% WP DDT in 100 gallons of water). Applications of DDT were first applied in the outbreak zone then extended outwards. The cover and ground sprays were repeated every three weeks. Two sprayers operated each power unit with a 250 ft length of hose attached. By 1950 the Department had 6 power spray units.

During the late 1950s it was found that DDT could harm bees, particularly if applied when the trees were in blossom. DDT killed natural enemies of insect pests causing secondary outbreaks, such as the upsurge of red scale at Klemzig in 1957. Nevertheless, DDT continued to be used because the side-effects were not thought to be sufficiently important to justify the omission of this important part of the eradication campaign.

Review of use of DDT

The South Australian Fruit Fly Conference in 1957 recommended that DDT be discontinued because of its side-effects. It was recommended that trichlorfon (Dipterex®) be substituted as a cover spray, since it was being used successfully by commercial growers. However, trichiorfon was not substituted because it had greater mammalian toxicity than DDT. In 1962, DDT was applied every 1 to 4 days within the 1/4 mile radius area and every 21 days outside this area. Spraying continued throughout the winter and spring months. Boxthorns that were trimmed to dimensions laid down under the Noxious Weeds Act, were also sprayed. If these bushes were not trimmed within a specified time, they were sprayed with arsenic under supervision and destroyed.

Increasing public concern about the harmful side effects of DDT led to replacement with a new organophosphate insecticide fenthion (Lehaycid®) as a cover spray in 1963. The possibility of spraying it by air was suggested but it was known that small birds were susceptible to fenthion and there was also a problem of contaminating drinking water collected from household roofs sprayed with insecticide. So, the idea of aerial spraying outbreak areas in Adelaide was never put into practice.

The aim of cover spraying was to contact all susceptible fruit on trees in the outbreak area by a fine deposit of the insecticide. Applications of 0.05% fenthion were made monthly and continued throughout the winter. Later, the concentration of fenthion within the 1/4 mile radius area was increased to 0.08% for the first spray and reduced to 0.04% during each monthly spray thereafter. In the 1/4 to

1/2 mile radius area, the concentration was 0.04%. The mixture at 0.08% concentration was 567g of fenthion (50% Lebaycid®) in 363.6 litres of water.

At that time, fenthion was not used in the United States of America and no analytical techniques were available and the breakdown products were unknown. However, in South Australia, fenthion proved to be satisfactory in killing fruit fly eggs and larvae at all stages of development in the fruit tissue. Fenthion was sprayed on an area at 14 day intervals. It could also be used on some plants previously burnt by DDT and was not likely to cause outbreaks of red scale. However, as it was very poisonous to small birds, care was required when spraying near aviaries. Fenthion was also tried as a ground spray, but its usefulness was limited as it was effective in the soil only for a short time.

To protect workers handling fenthion, gloves, overalls and respirators were supplied and the workers were briefed on the correct method of handling and applying cover spray. By 1973, there was the capacity to field 25 teams of sprayers, operating from 25 power spray units.

From about 1972, householders were advised by cards of spraying on their property. The leaflet also contained information on the withholding period before fruit could be consumed and advice on washing the fruit.

Deletion of cover spray for Qfly

By the early 1970s cover spraying was becoming less accepted by the public. There were fears about damage to the environment, deaths of birds and effect on beneficial insects by concerned conservationists and opposition to the current methods increased. Cover spraying was eliminated in 1974 as the emphasis had changed from attempting to kill the immature stages of the pest to killing the adult flies by baiting. However, in this year, the baiting technique appeared to fail, and a modified form of cover spraying was re-introduced. Fenthion was sprayed in an area of 200 to 400 metre radius from the outbreak centre. On 11 November 1974, the Fruit Fly Technical Committee decided cover spraying for Qfly once again could be eliminated, as baiting was adequate to eradicate outbreaks of Qfly; this procedure remains today.

A cover spray of 0.16% fenthion continued to be applied to the outbreak zone of Medfly outbreaks. Cover spray for Medfly was applied to trees bearing fruit and sufficient spray was applied until it began to drip off the leaves. Spraying was every 10 days and it continued for 3 spray periods after the last fly or larva was detected. The withholding period was 7 days before the fruit could be used, and the householder had 3 days to use the fruit before the next spraying. Cover spraying continues to be applied in the outbreak zone of a Medfly outbreak and usually 3 applications at 10 day intervals are applied.

The importance of cover spraying in the outbreak zone was demonstrated in 1980 when cover spraying was omitted at the start of an outbreak of Medfly at Panorama. Flies were still being trapped for 2 months after the commencement of the outbreak, cover spraying was resumed.

Ground spraying

DDT, as a ground spray, was used in 1947 under trees where fallen fruit may have been infested with larvae. The aim was to kill larvae as well as adults which emerged later.

Safer and more effective insecticides to be used for treatment under trees were examined, such as lindane and granulated dieldrin. Until 1962, DDT was used as a standard treatment under all fruit trees within the outbreak zone, along with dieldrin under infested trees.

Another organochlorine, chlordane, was used as a ground treatment for the first time in 1980 and was applied under trees whose fruit was infested with larvae. The rate of chlordane was 1.25% (1L of chlordane to 80L of water) and about 13 to 14 litres of the solution was applied under each infested tree.

Chlorpyrifos (Lorsban®) replaced chlordane as ground treatment in 1987, as the Department was concerned at the long—term effects that chlordane has in the soil when plants, particularly vegetables, are grown on the site that was sprayed. The rate to be used was 0.176%, i.e. 30mL Lorsban® (500 g/L chlorpyrifos) in 17 litres of water, with 2 to 3 litres of this solution applied per square metre, depending on soil conditions. This treatment is still used in 1997.

Removal of fruit

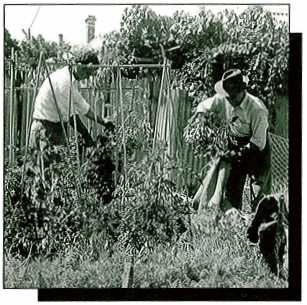

The eradication procedure during the summer of 1947 included the complete stripping of all fruit from trees within a one mile radius of the centre of the outbreak. The removal and safe disposal of the fruit was aimed at destroying existing larvae, and removal of oviposition sites for female flies still within the area. The removal of fruit to deprive female flies of oviposition sites did not have a sound biological basis, and changes in this procedure are based on the theory that host fruit be left in the outbreak area to encourage female flies to remain.

The first stripping was aimed at the most attractive hosts of the fruit fly, including apricot, peach, nectarine and plum. When the first stripping was complete, other hosts which, in the absence of more attractive fruit, might provide oviposition sites were removed from mandarin, guava, grapefruit, persimmon, cumquat, japonica, orange, ornamental peach, shaddock, ornamental plum, lemon, crab apple, medlar, cape gooseberry, tree tomato, ornamental solanum, prickly pear, grape vines, figs, feijoa, apple, pear and quince. Annual bushes were removed whole: apple of sodom, sweet melon, tomato, bitter melon (weed), peppers, paddy melon (Weed), eggplant, squirting cucumber, rockmelons and cucumbers. Citrus was stripped during the winter period and blooms from loquat trees were removed to prevent cropping. A Proclamation prohibited, within the outbreak area, the planting or growing, either under glass or in the open, the following plants during the period from the 1 March to 31 October: tomato, sweet melon, capsicum, rockmelon, egg plant and pepper.

In 1949, some entomologists suggested that fruit removal be abandoned because flies deprived of hosts would disperse, making eradication more difficult; however, this idea was not adopted. In 1953 there was a large public outcry against the stripping of fruit trees and the resulting costs, waste, damage and claimed injustice that occurred. Householders petitioned to register gardens and take on measures themselves to combat the fruit fly. However, even this was not sufficient to change existing practices.

In 1964, Dr Steiner of the USDA after, observing operations in South Australia, recommended only stripping of all fruit from infested gardens, and only ripening fruit over the remaining 1/2 mile radius from where the larvae were detected. Winter stripping of citrus over the entire one mile radius area was continued to ensure a host free period from early spring (when the temperature was high enough for egg laying), until the start of the stone-fruit season in early October. Stripping was further reduced in 1967 when only ripe host fruit was removed from the area within 1/4 mile radius of where fruit fly was detected. In 1974, stripping was abandoned and baiting was introduced as the main eradication technique. Unfortunately, an outbreak treated in this way was not controlled and stripping was resumed within an area of 1/8 of a mile radius. After careful checking, operators found that the control failure was due to incorrect formulation of the bait—insecticide mix, and not related to non-removal of fruit. in 1975, only fruit on infested trees and host trees in the same yard were removed, and ripening fruit, as before, was retained to reduce the tendency for a female fly to move from the area. By the mid-90s, at either a Qfly or Medfly outbreak, only fruit from infested trees, and nearby fruit trees at risk, is removed. Under certain circumstances householders could request removal of fruit instead ofhaving cover spray applied during Medfly outbreaks.

Disposal of fruit

Complaints about the smoke nuisance at Magill in 1957 prompted the Department to move this operation. Burning was done at the Dry Creek dump but, because of smoke nuisance and an objectionable smell, permission to burn there was withdrawn. Plant material was then burnt at the Wingfield dump.

In 1967, both stripped fruit and green plant material was taken to the Tea Tree Gully dump, treated with diesel oil and DDT and covered with 4 feet of overburden. This was effective in preventing emergence of flies, was more convenient than dumping at sea and the cost was halved. At Pt. Augusta, the stripped and bagged fruit was carted to Curlew Point and tipped into holes drilled by the ETSA and covered.

The problems of the disposal of fruit ceased when stripping was greatly reduced in 1975. Presently, fruit is tied in plastic bags after treating with maldison powder and buried under 2 metres of soil.

Male annihilation

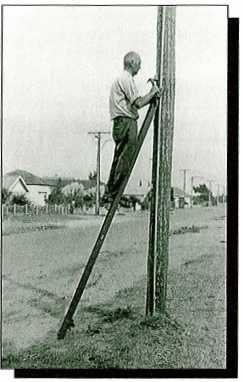

A new method of attracting and killing male Qflies was added to the eradication procedures in 1967. Treated absorbent 4 inch x 3 inch caneite blocks, called ‘killer pads’, were impregnated with l0ml of hydroxyphenyl butan 3-1 118.3mL+ Acetoxy phenyl butan 3-1 118.3mL+ Technical maldison 236.6mL dissolved in 4544 ml absolute alcohol applied to each side of the pad.

The pads were placed on a 60 yard grid (2,000 per square mile) throughout the outer 1/2 mile area of an outbreak. They were hung or nailed to suitable trees or telephone poles (with PMG permission) at least 8 feet from the ground so as to be out of the reach of children and their location recorded.

The effective life of the pads was believed to be 12 months, after which they were collected and destroyed. The lure pads were used until 1978, when it was found that their continued use interfered with the lure traps used in to detect outbreaks; some flies went to the caneite pads and died, instead of being attracted to the lure traps in the area.

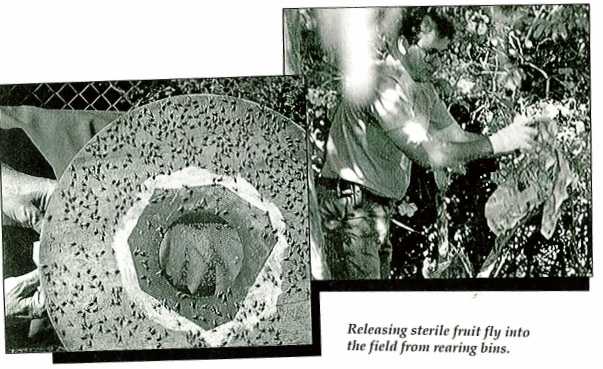

Sterile Insect Technique (SIT)

University of Adelaide entomologists, headed by Professor H.G. Andrewartha, and including John Monro and Noel Richardson were the first to use SIT in Australia. Their aim was to test whether the method would be suitable for eradication of South Australian Qfly outbreaks. Unable to carry out this research in South Australia, they selected a number of towns in western New South Wales for field trials between 1962 and 1965. The flies were reared in a small insectary behind the School of Zoology, Sydney University, and irradiated at the Australian Atomic Energy Commission establishment at Lucas Heights.

These entomologists demonstrated that the method used in New South Wales could be used to eradicate populations of Qfly which were larger than most South Australian outbreaks. Since this demonstration, it has taken another 30 years for this method to be used in South Australia. It was not until sterile Qflies were readily available from a factory in New South Wales was the method used to treat South Australian outbreaks.

SIT was first used by Peter Bailey and Nick Perepelicia, of Primary Industries South Australia, to treat an outbreak of Qfly in Adelaide from 23 February to 15 May, 1993. In this, and subsequent releases to the 1996/7 season, the area is protein-baited for two weeks, and sterile flies are released for the following 8–10 weeks.

Costs and benefits

The identifiable beneficiaries of the fruit fly policy of the South Australian Government have been home gardeners and sections of the horticultural industry.

Home gardens

It is likely that the ability to grow fruit in South Australian home gardens without suffering fruit fly damage, or alternatively, without having to treat with insecticide, has encouraged home production of fruit in many households. In 1976, it was estimated that $22m of fruit was produced in South Australian home gardens, based on survey results showing four fruit trees per residence.

Horticultural industry

Of the horticultural industries, the citrus industry has benefited from the internationally-recognised fruit fly freedom status to export fruit, particularly to the US and New Zealand markets, without the necessity of disinfestation treatments which add to costs and reduce the quality.

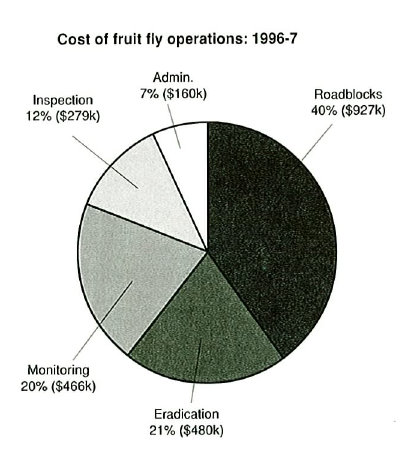

Costs

All costs of fruit fly operations in South Australia have been paid by the South Australian Government.

The comparative costs of components of fruit fly operations during the 1996/7 year are shown in the pie diagram. The relativities will change from year to year, depending on the number of outbreaks, but the costs of other components do not vary much in recent years.