Hay & fodder conservation in SA

Hay and chaff has been conserved as animal feed in South Australia since the colony’s establishment in 1836. Straw, a by-product of wheat grain harvesting, was used for animal bedding and mixed with clay to build ‘wattle and daub’ housing, used as a roofing material and as bedding for animals. Clydesdale horses were mainly used to draw all farm machinery. Chaff, chopped hay, was main source of feed for horses and chaff mills were a common business around Adelaide and South Australia.

Stooking

Hay was cut by hand with sickles in the early days, but horse drawn twine binders were developed around 1885. These machines made sheaves of directly cut cereals, wheat, oats and barley. The binder would cut the herbage with a knife bar mower, a reel and canvas elevator would convey the stalks to a binding platform where they were tied by a knotter with twine to form a sheaf. This was dropped on the ground for initial drying. After a few days drying, sheaves were stooked with pitchforks and final drying and curing occurred before carting to the stack. Stacking was a skill and great pride was taken in forming a symmetrical haystack. Often salt was added to each layer of the stack to retard mould growth.

With the advent of tractors, especially the small grey Ferguson in the 1940s, horse draw binders were adapted to be towed by these machines. Stationary balers were starting to be used to make rectangular 25 kilogram hay bales. Wire was used to tie the bales. Pasture or cereal hay was cut with sickle bar mower, dried, raked into a windrow then transported to the baler. In the 1950s, tractor pulled balers, manufactured by New Holland, Massey, International, and McCormick, were producing 25 kg rectangular bales. This mechanisation allowed for increased hay production, especially after the introduction of bale loaders attached to the side of the truck. Some farmers loaded 25 kg hay bales onto trucks manually with wool bale hooks. In the 1950s Allis-Chambers balers were producing 25 kg round bales. Larger 40 kg fodder rolls were produced by Econ Fodder Rollers in the early 1960s. Various systems of conserving loose hay were also in use. The JayHawk system was another method of conserving loose hay. Hay was made and generally stored in the corner of the same paddock.

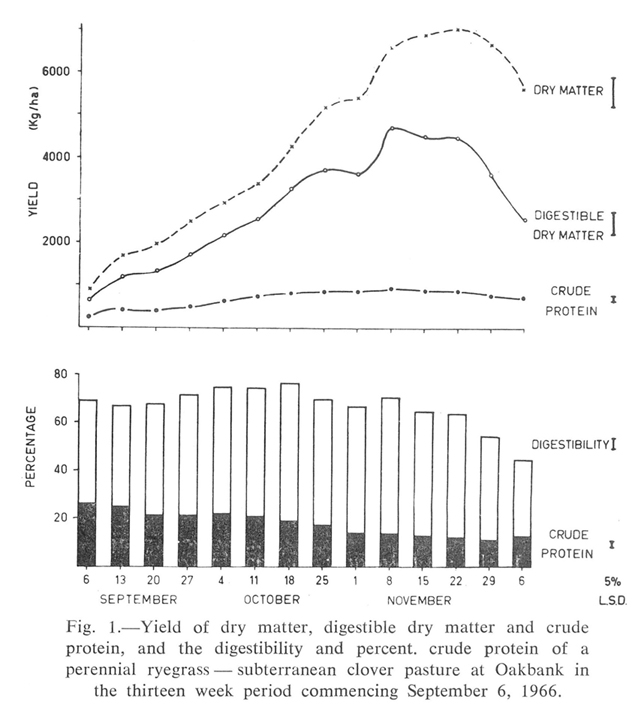

In the 1960s fodder conservation mechanisation increase with the introduction of disc mowers, mower and windrowers, mower-conditioners, conditioners and a variety of hay rakes and tedders, however, tedders were not commonly used in South Australia. During this period the Dairy Branch of the South Australian Department of Agriculture began conducting research into fodder conservation. A laboratory set up at the Northfield Research Centre by to carry out in vitro digestible dry matter and kjeldahl crude protein analyses.

In 1968 research on the nutritive value of common South Australian pastures and cereal varieties was carried out. This research stressed the importance of early cutting. Cutting when the dominant grass in pasture swards was at the early flowering stage (wheat, barley and triticale at the milk stage and oats at flowering) produced hay that was high in digestibility and digestible dry matter production. This research demonstrated the importance of improved fodder quality and allowed dairy extension staff to advise dairy farmers on the relationship between digestibility and increased milk production. Northfield staff also attended Agricultural Bureau meetings throughout the state communicating the value of hay quality. Farmers would have their hays tested at Northfield and the results would form the basis of fodder quality discussions.

Radcliffe, J.C., and Newbery, T.R., Proc. Aust Soc. Anim .Prod.6; 66

During 1974, prominent Kapunda chaff millers, Max and Clyde Johnson, began having feeds tested at Northfield. They had developed technology to unroll large round bales to cut into chaff. The main consumers were the local racehorses.

With the increased awareness in the farming community of fodder quality, the Royal Agricultural and Horticultural Society of South Australia Incorporated took an interest in having hay tested by the Northfield laboratory. Since the inception in 1839 of its precursor, the South Australian Agricultural Society, the Society had been a source of information on hay machinery and farming practices. Judging of hays at the Royal Adelaide Show was based on a visual appraisal until the late 1960s. The Agricultural Produce Committee (now Grains and Fodder Committee), under the chairmanship of Roy Hentschke, requested digestibility and crude protein analyses on the hays and chaffs entered in the fodder classes, and the Society has since used objective laboratory tests in its judging to create further awareness of fodder quality in the farming community.

Early hay cutting in southern Australia increased the risk of hay spoilage through mouldiness due to increased probability of rain. Milk production studies at Northfield

demonstrated that mouldy early cut cereal hay, even when spoilt by 93mm of rain, was still marginally better than late-cut hay.

The use of potassium carbonate on drying lucerne and caustic soda on cereal straws were also investigated at Northfield. Potassium carbonate significantly reduced hay drying times, hay being ready to bale 24 to 36 hours after cutting. Caustic soda was found to increase digestibility of cereal straw from 45 to 55 per cent.

With the advent of large hay packages stored in the open and increased mechanisation, a survey of various haymaking systems was conducted throughout South Australia. Machines that picked up ninety-five 25 kg bales in the paddock for stacking onto a truck for transport to sale or into hay stacks were in use in the 1970s by a limited number of hay growers.

300kg round baler

A study made of various hay packages stored in the open. Previous hay storage studies of 25 kg rectangular bales stored under cover had shown only small weight losses of up to five per cent over three years with little effect on its nutritive value. Compressed stacks of 800 kg, 300 kg round bales and 300 kg round bales of both cereal and pasture hay were stored in the open over 15 months at Northfield (500 mm rainfall) and Hindmarsh Tiers (1100 mm rainfall). It was found there were low losses in dry matter when hay as held in open storage over summer, but winter rainfall resulted in losses of 37 per cent dry matter.

Feeding racks for large round bales were widely adopted. A round bale feeder was designed for attachment to a front end loader of a tractor and allowed bales to be rolled along the ground for feeding to cattle.

Machines to make large 600 kg rectangular bales became more common in the 1980s.

In the late 1980s J T Johnson and Sons entered export hay markets in Japan, South East Asia and the Middle East. At that time, annual ryegrass toxicity had become a problem on cereal - sheep properties in the mid-North of the state. Introducing a cereal hay crop in the rotation was an effective method of controlling this disease. Quality control of export hays to ensure freedom from toxic ryegrass was achieved by the introduction of a toxicity testing service now conducted by SARDI. In the 1990s Balco (the Balaklava Company) became an additional hay processor and exporter. By 2010, Australia’s annual hay exports to Japan, Taiwan, Korea and China were about 700,000 tonnes. Export Hay has become a significant source of income for local farmers. Hay purchased from growers is analysed for a variety of parameters that may be useful in feed formulation. As well as dry matter, digestibility and crude protein, data are provided for acid detergent fibre, neutral detergent fibre, water soluble carbohydrates, metabolisable energy and total digestible nutrients.

The hay is compressed into small (“double dumped”) 25 kg bales to allow better utilisation of shipping container space. Only 17 tonnes of a large 600kg bale would fit into a standard container, but compressing or double dumping allows 26 tonnes of hay to fill the container. A variety of packages has been developed for container shipment from 25 kg to 500 kg (examples - external link), some of which involve stretch plastic wrapping. Enforcement of strict moisture standards (below 14 per cent) prevents hay deterioration during storage. As part of quality assurance procedures, export hay may also be X-rayed to ensure it is free of contaminants (“hardware”).

The results of all 1970 and later hay and silage research culminated in a bulletin “Conserving Fodder” AGDEX 100/50, Bulletin 3/83 (revised December 1994) ISBN 0 7243 7529 5, Printed by State Print, Adelaide, South Australia.

Martin J Cochrane, July 2009.