Meat hygiene in SA

Regulation of any activity reflects the aspirations and expectations of the community at a point of time. The regulation of meat hygiene in South Australia clearly reflects this with the very early legislation being primarily related to the new colony having a supply of fresh meat. Due to the absence of cooling and limited transport, local communities required a slaughterhouse in near proximity to meet their needs.

As district and regional production outstripped demand new arrangements were required to meet the needs of export markets, hence the legislation passed in the early 1900s that placed increasing emphasis on food safety, particularly that related to pests and diseases.

More recently production and consumption trends have changed and so too has meat hygiene legislation which now caters for a wider range of production diseases, expectations of safe and quality specified meat, changes in cooking times and the demand by supermarkets for food with a longer shelf life. This led to the current situation where the Department has much of the legislative responsibility for the production of safe meat and the requirement for meat businesses (production, processing, manufacturing, transport and retail) to have risk based food safety programs.

History of Meat Hygiene

Meat hygiene, in varying forms, often induced by religious taboos, can be traced to biblical times.

An early reference to religious taboos is where Moses made pronouncements from the mountain on a range of issues including what meat can be eaten or not. The statement in the Bible referring to pigs is:

"Do not eat pigs. They must be considered unclean; they have divided hoofs but do not chew the cud. Do not eat any of these animals or even touch their dead bodies". Deuteronomy Chapter 14

Writings in the Old Testament were not only followed in Christians but by Islamic followers as well.

The non-consumption of pig meat by the Jewish and Moslem communities was also seen as a reflection of the level of microbial contamination and keeping quality of pig meat. Further, the association between pig meat and subsequent human illness can often be attributed to a zoonotic nematode called Trichinella spiralis (trichinosis).

Trichinosis was endemic in USA and some parts of Europe until the 1960s.

Roman butchers were fined for selling uninspected meat.

Fourteenth century English records indicate some controls over the standards of publicly sold meat and the waste from slaughtering.

The United States began compulsory inspection of meat destined for human consumption as early as 1891.

Canada claims a history of three centuries of meat hygiene legislation with initial public health legislation passed in 1706 which required slaughtering to be approved by the King's Officer and meat to be inspected prior to public distribution. Compulsory meat inspection was introduced in Canada in 1907.

The European Community enforces strict directives to maintain high standards of fresh meat for human consumption. Regulations govern slaughterhouses, equipment, storage and transport and standards of hygiene.

In South Australia there have been four main periods of meat hygiene regulation:

Period 1 – 1836 to around 1910

During this period the main purpose of legislation was to control the orderly establishment and management of meat processing works to ensure a supply of fresh meat to domestic consumers. Local government was the main administering body. Near the latter part of this time the quantities of meat exported increased requiring a level of inspection to meet the regulatory requirements of the importing country. The safety of foods was regulated by the Food Act (administered by public health authorities).

Period 2 – 1910 to 1980

During this period there was greater emphasis on meat hygiene; however this was primarily regulated by specifying the construction and operation of abattoirs and slaughterhouses, and meat processing works. The Food Act remained the main legislative tool to manage food safety aspects of meat.

Period 3 – 1980 to 1994

During this period, regulation of abattoirs and slaughterhouses was taken over by a new 'Meat Hygiene Section' within the Animal Health Branch of the Department of Agriculture. A single inspection service was introduced with improvements to infrastructure in works. Pet food was incorporated into the legislation.

Period 4 – 1994 to the present

This was a period of rapid regulatory change with the establishment of a separate Meat Hygiene (later Food Safety) Unit within the Department, replacement of traditional organoleptic meat inspection with mandatory HACCP-based (externally audited) quality assurance programs throughout the meat processing industry, expansion of the meat hygiene program to include all meat products including poultry, processed meats and game meat, the transport and storage of meat products and the withdrawal of State Health and Local Government and the Commonwealth (which had been providing on-plant veterinary and meat inspection services) from the domestic meat hygiene program. More recently the Department took the responsibility from Health and Local Government for most of the meat retail (butcher) outlets.

Early South Australian Legislation

On 8 December 1840 the Parliamentary Council passed an Act to Regulate the Slaughtering and Prevent Stealing of Cattle. This was one of the earliest pieces of 'agricultural' legislation to be passed by the Parliament in the new South Australian colony.

The Act stipulated that "no person shall keep a slaughterhouse or place for slaughtering cattle intended for the sale, barter, shipping or exportation without it being duly licensed". The Act controlled the number of slaughterhouses in Adelaide and within three miles of the exterior boundary. The issuing of a license was the responsibility of the Bench of Justices within the Magistrates Court.

The Act also provided for licensing slaughterhouses outside of the metropolitan area and for his Excellency, the Governor to appoint inspectors of slaughterhouses in such towns and districts.

Specific provision was made in the legislation to exempt persons slaughtering cattle at their own residence for domestic consumption.

The provision in the legislation about the steeling of cattle was covered by the requirement for the skin of slaughtered cattle to bear the brand of the owner and for the skin to be retained with the brand for a certain time. To administer this part of the Act the Government established the 'Cattle Registry Office' under the "superintendance" of the Inspector of Brands. The role of the Inspector of Brands was to allocate a brand to a person. The inspector also held records of the number of cattle slaughtered.

At a similar time the Food Act was passed that legislated aspects of food safety.

The Abattoir Acts of 1908 and 1911

While the need for proper hygienic practices in the slaughter of animals for meat and the subsequent handling of meat products had been recognised for centuries, effective implementation of such practices were slow to develop. Initially seen in South Australia and elsewhere as an appropriate responsibility of local government, this was not formalised until the Metropolitan Abattoirs Act 1908 and the Abattoirs Act 1911 respectively provided a legal framework for a central meat works at Gepps Cross and authority for municipalities to establish an abattoir with a certified meat inspection service.

The Acts gave Local Government Municipalities authority to establish an abattoir in which all meat and meat products offered for sale within that Municipality had to be prepared in the Municipal Abattoir and inspected by a qualified meat inspector employed by the Municipality.

As a result, Local Government Abattoirs were established in Adelaide, Port Lincoln, Whyalla, Port Augusta, Port Pirie, Mount Gambier and Port MacDonnell.

Another group of abattoirs, notably the bacon factories in the Adelaide Hills, which were not metropolitan abattoirs, were provided with an inspection service by the State.

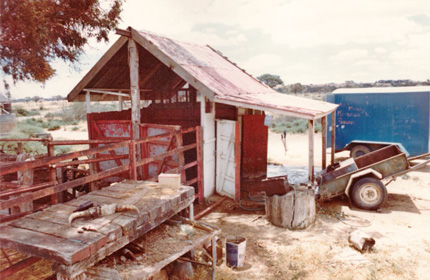

In non-metropolitan areas meat was prepared in slaughter-houses operated by the local butcher and inspected, irregularly and sometimes notionally, by local government health inspectors.

However, many export markets, especially in the USA, demanded an inspection service supervised by veterinarians. In South Australia this service was provided in export-approved meat plants by the Commonwealth Department of Primary Industries.

Typical non-metropolitan slaughter-house operated by the local butcher, taken around the mid 1900s

Typical non-metropolitan slaughter-house operated by the local butcher, taken around the mid 1900s

Typical non-metropolitan slaughter-house operated by the local butcher, taken around the mid 1900s

Typical non-metropolitan slaughter-house operated by the local butcher, taken around the mid 1900s

First shipment of frozen lamb from Pt Lincoln abattoir, 1930

South Australian Meat Corporation Act (1936–1976)

The South Australian Meat Corporation Act 1936 established the SA Meat Corporation (SAMCOR) as a replacement to the Metropolitan and Export Abattoirs Board.

The Metropolitan Abattoirs Area was established (or maintained - depending on previous legislation) which gave SAMCOR the sole right to slaughter stock within the Area. This resulted in restricting the development of abattoirs outside the metropolitan area as these works could only sell to local outlets or, if they had a permit from the Minister, to export.

An amendment to the SAMCOR Act in 1976 and the repeal of the Port Lincoln Abattoirs Act (1937) saw the Pt Lincoln works transferred to SAMCOR in 1977.

Health Act (1935–1975)

The Health Act, as would be expected, was very comprehensive; however it included a number of provisions impacting on meat hygiene.

The Act set standards for council licensing of slaughterhouses, prevented the feeding of swill to pigs, prohibited dogs from slaughterhouses and access to offal and controlled the sale of contaminated or diseased meat or offal. The Act also set clear guidelines for the construction of slaughterhouses and operations.

The provisions of the Act were implemented by local government health inspectors.

Meat Hygiene (1908–1980)

Thus by the early 1960s three formal meat inspection services, and a somewhat less formal local government service, operated in South Australia. This inevitably resulted in anomalies, overlaps, inequities and inefficiencies.

In 1965, South Australia, alone among the States, took advantage of the Commonwealth Meat Inspection Arrangements Act which enables the Commonwealth to provide a meat inspection service for a State or State Meat Authority. This resulted in a rationalisation of the meat inspection service in South Australian abattoirs over the following years.

During the early 1970s in particular, a number of significant changes occurred in the meat industry, due to increases in:

- the intensive management of livestock pre-disposing to salmonella and other diseases associated with high stocking densities

- the mobility of livestock and meat products due to improvements in transport

- the use of mechanical meat processing machinery

- the quantity and diversity of smallgoods and ready to cook meals

- the number of take-away food shops and restaurants

- the trend towards cooking meat less before eating

- the number of country butchers peripheral to Adelaide who supplied 'Country Killed Meat' to city customers

- requirements of supermarkets for longer shelf life.

The above changes, which were not accompanied by the relevant improvements in meat hygiene standards and practices, indicated the need to review the current standards and practices.

In 1975, a Meat Industry Bill covering all aspects of the industry from slaughtering to marketing was drafted. This involved the establishment of regional abattoirs. However, Samcor, which was perceived as a regional abattoir, was incurring considerable losses annually. The Bill was therefore rejected by Cabinet.

In May 1976, the Minister of Agriculture established an Interdepartmental Committee to report on options for the implementation of meat hygiene standards in South Australia. The departments were Agriculture and Fisheries, Public Health and Premier’s.

The Committee reported to the Minister in February 1977. Its principal recommendations were:

- the enactment of a single piece of legislation covering all aspects of meat hygiene in South Australia

- the repeal of the Abattoirs Act

- the amendment of other Acts relating to it;

- The Samcor Act

- The Local Government Act

- The Health Act

- that responsibility for meat hygiene be vested in the Minister of Agriculture with responsibility for implementing the Act vested in a Chief Inspector

- the adoption of two categories of establishment; abattoirs and slaughterhouses

- that all meat for human consumption be inspected

- that pet food establishments be included in the legislation

- that, while poultry meat hygiene was not within the Committee’s terms of reference, it would be appropriate for standards to be included in the legislation.

This report formed the basis of the Abattoirs and Pet Food Works Bill of 1978.

There was considerable resistance to the implementation of many of these recommendations not the least of which came from the poultry meat industry which was aware of the questionable standards in some parts of the red meat industry, and did not wish to be included in the same legislation.

The Bill was debated in Parliament and referred to a Select Committee of the Legislative Council but lapsed following the State Election of September 1979.

In November 1979, a Joint House Select Committee was established to enquire into and report on matters relating to meat hygiene. The Committee reported to Parliament in March 1980, the Meat Hygiene Bill 1980 was introduced to, and passed through, Parliament, receiving Royal Assent in April 1980.

The Act provided for:

- the establishment of a Meat Hygiene Authority (MHA) with three members,

- a Chief Inspector appointed by the Minister of Agriculture,

- a person nominated by the Minister of Health, and

- a person nominated by the Local Government Association of South Australia

- the establishment of a Meat Hygiene Consultative Committee.

- a single inspection service, provided by the Commonwealth, for all domestic abattoirs

- improvement of hygiene and construction standards of slaughterhouses and restrictions on the sale of meat prepared therein.

- licensing of Pet Food Works.

A good summary of the situation at this time is to be found in a presentation on Meat Hygiene in South Australia () by Dr John Holmden, the then Chief Inspector, to an early meeting of the MHA and Meat Hygiene Consultative Committee.

Poultry Meat Hygiene was to be covered by a separate Act, the Poultry Meat Industry Act.

The inspection service provided by the Commonwealth applied, in addition to licensed export plants, to domestic plants designated as regional abattoirs only. It did not apply to nearly 150 local slaughterhouses, most supplying a single country town; these continued to be subject to periodic checks by MHA inspectors and notional inspection by local government health inspectors.

Distribution to major cities and regional centres in SA was restricted to meat processed in licensed domestic abattoirs – characterised by different structural requirements and on-plant, full-time meat inspection. Sale of slaughterhouse meat in major centres was prohibited.

Australian lamb on display in London, 1937

Meat Hygiene Act 1994

The Meat Hygiene Act 1994 was the result of:

- the Organisational Development Review (McKinsey 1992) which determined that meat hygiene was not “core business” of the department of Primary industries – because it was considered primarily a public health issue, and the Meat Hygiene Authority was seen as expensive, inefficient and dysfunctional.

- the escalating cost of AQIS meat inspection and veterinary services (in a “cost-recovery” initiative), which was imposing heavy cost pressures on domestic abattoirs.

- concern that large sectors of the meat processing industry were not subject to hygiene standards or regular audit.

- complaints of inequities and dysfunction in the domestic industry, with ongoing allegations of poor hygiene in slaughterhouses, illegal entry of slaughterhouse meat into regional centres, discrimination against country butchers and different hygiene standards in force between cities and country towns.

- initial consultations (by the Acting Chief Meat Hygiene Officer, Dr Robin Vandegraaff) in 1993 with both AQIS and the Department of Health, with a view to transferring responsibility for meat hygiene to either authority, in line with McKinsey’s recommendations, and subsequent decline by both – AQIS on a full cost-recovery model and Health because it viewed meat hygiene as a market access activity.

- a consequent decision in late 1993 by the PIRSA Chief Executive to retain and rebuild the meat hygiene function within PIRSA, with new terms of reference and a new regulatory model based on quality assurance, similar to a new program emerging in Victoria.

The Meat Hygiene Act was drafted in late 1993 and early 1994, loosely based on the evolving Victorian legislation and subject to ongoing scrutiny by a Parliamentary committee. It passed both Houses in May 1994. Regulations were prepared and the Act and Regulations became law in December 1994, with a transitional period of three months.

The new Meat Hygiene Act 1994 broadened the legislation to include the processing of game meat, along with boning out and further processing, manufacturing of smallgoods and the storage of meat and meat products (including poultry) for wholesale. The transportation of meat and meat products along with game meat field processing operations were later included in the meat hygiene program.

The Act also established the South Australian Meat Hygiene Advisory Council, which replaced both the Meat Hygiene Authority and the Meat Hygiene Consultative Committee. The Council had an independent Chair and its role was to advise the Minister on the administration of the Act and other matters relating to meat hygiene in South Australia.

The newly formed Meat Hygiene Unit, with 3 staff headed by the new Chief Meat Hygiene Officer, strongly supported by the new Advisory Council, chaired by Gerald Martin, immediately wrote to about 400 known meat processors in South Australia (in all sectors except retail), inviting them to apply for accreditation under the new Act.

In January 1995, during the period allowed for applications, a major food safety incident occurred in Adelaide – Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome, caused by enterohaemolytic E coli, in a fermented meat product.

One of the many outcomes of that incident – in addition to tragic and ongoing disease in some people, many bankruptcies (especially in the smallgoods industry) – was a substantial increase in funding for the new Meat Hygiene Program, strong industry support and co-operation, accelerated industry training in HACCP-based food safety and quality assurance and a new regulatory system based on independent audit of food safety QA throughout the industry.

The Act was reviewed in 2000 with the principal recommendation to broaden the scope of the Act to cover retail meat processing operations (butchers), including supermarkets. Regulations came into effect in 2004 which effectively transferred the responsibility for this activity from local government to PIRSA.

Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) Act 2004

The passing of the Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) Act 2004 was a clear indication of the transfer of responsibility to PIRSA. This period also saw the development of Australian Standards for the hygienic processing of meat and meat products for all species. The respective Australian Standards were developed by the national Meat Standards Committee (MSC) which was made up of representatives from each State and Territory, the Commonwealth and peak industry bodies. One function of the MSC was to ensure that the Australian Standards were applied consistently in all jurisdictions. Subsequent to the development of the Australian Standards was the introduction of primary production and processing standards (PPP Standards) in the national Food Standards Code. In the case of meat, a separate PPP Standard was developed for poultry meat and one for all other meat producing animals. The PPP Standards are now called up in legislation in every jurisdiction.

The Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) Act 2004 came into effect in 2005 with gazettal of regulations for the dairy food safety scheme. The Act brought together existing primary industry food safety legislation into one act so that sector specific food safety schemes could be established as Regulations.

The Regulation for each scheme defines the food safety requirements and administrative arrangements for the sector. A food safety scheme for the meat industry was developed as a specific Regulation.

The Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) (Meat Industry) Regulations took effect from July 2006. The Regulation created the South Australian Meat Food Safety Committee.

The meat food safety scheme was extended in 2013 to include poultry production.

Separate food safety schemes also exist for eggs, plant products, seafood and citrus. In most cases, each regulatory scheme calls up and mandates compliance with the applicable national primary production and processing standard established within Chapter 4 of the Food Standards Code.

In the case of the meat food safety scheme, both Standard 4.2.2 (Primary Production and Processing Standard for Poultry Meat) and Standard 4.2.3 (Production and Processing Standard for Meat) are called up as mandated Codes in the regulations.

Standard 4.2.3 has a strong focus on requirements for the production of ‘high risk’ meat products, such as uncooked fermented meat products. There are also a number of codes and guidelines which assist producers in compliance with the regulations and Standard 4.2.3, for example the MSC Guideline ‘Regulatory guidelines for the control of Listeria’, and the ‘Guidelines for the Safe Manufacture of Smallgoods’ published by Meat and Livestock Australia Ltd.

Under current day arrangements, processors must manage food safety requirements through a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) based Food Safety program that is subjected to regular audits by persons authorised or approved by the Minister. The frequency and number of audits and inspections of the accredited business operation is determined by the Minister, and the cost of audits is borne by the accredited operator.

And well-run slaughterhouse and meat processing operations in country towns in SA can now sell meat anywhere in Australia.

The success and evolution of the Meat Hygiene program since 1994 is a major achievement in PIRSA in the last 20 years, due in no small measure to the staff in it. In particular the leadership of Robin Vandegraaff and later Geoff Raven and the contributions by Bob Thomas, Peter Dean and Geoff West has been a major factor.

Chronology

1840: Act to Regulate Slaughtering and Prevent Stealing of Cattle

1908: Metropolitan Abattoirs Act

1911: Abattoirs Act

1936: South Australian Meat Corporation Act

1936: Metropolitan and Export Abattoirs Act

1969: Poultry Processing Act

1980: Meat Hygiene Act and Regulations

1984: Pet Food Regulations

1986: Poultry Meat Hygiene Act and Regulations

1994: Meat Hygiene Act and Regulations

2005: Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) Act

2006: Primary Produce (Food Safety Schemes) (Meat industry) Regulations

Author: This article was written by Dr Don Plowman, former Deputy Chief Executive of PIRSA, with contributions from Dr Robin Vandegraaff, Mr Geoff Raven (and the Food Safety Unit Group), Dr Tony Davidson and members of the History of Agriculture Working Group.

May 2015