Industry commodity sectors

Until 1900, South Australia’s stone fruit industry was focussed on fresh fruit production. Production of dried fruits expanded rapidly post WW1. There were similar periods of rapid expansion in the canned fruit industry post WW1 and post WW2. During the 1970s, South Australia’s stone fruit industries lost their competitive advantage for dried and canned stone fruit products. Today, SA’s stone fruit industry is almost entirely focussed on fresh fruit production.

Fresh stone fruit

Fresh peaches, nectarines, apricots, plums and cherries have always been important summer fruits for Australian consumers. Introduction of refrigerated cool storage, availability of varieties with a broader range of maturity dates, and development of stone fruit production in a wider range of climatic zones has expanded fresh stone fruit supply seasons significantly.

Initially individual orchardists packed and marketed their own fruit either locally or through agents in the major wholesale markets across Australia. Following WW1, a number of packing and marketing cooperatives were established in the major fruit growing districts. These cooperatives received fruit from growers, then graded, packed and marketed it to wholesalers. Declining profitability saw many of these cooperatives close through the 1970s to 1990s.

The national introduction of Plant Variety Rights (PVR) legislation in 1987 resulted in many new fresh peach and nectarine varieties being introduced from overseas breeding programs (particularly the USA). This resulted in development of exclusive marketing arrangements for new PVR protected varieties through contracts between licensed grower groups, nurserymen, and associated retailers.

Specialist marketing groups (such as the Quality Fruit Marketing (QFM) Group) emerged to take advantage of these new varieties and develop quality and marketing systems to suit the needs of particular retailers.

Fresh stone fruit exports

Exports of fresh stone fruit to Asia developed with the advent of air freight services (from Adelaide and Melbourne airports). Volumes fluctuated from season to season depending on supplies from other countries, availability of air freight space, and currency exchange rates.

The export of sugar plums expanded through the innovative thinking and pioneering spirit of Noel Sims (Simarloo), a grower and packer based at Lyrup. The D'Agen French prune plum was originally growncommercially in Australia for drying and prune production. Simarloo had large plantings of D’Agen plums.

With the decline in consumer demand for prunes and increased competition from imported product, Noel Sims was keen to identify new commercial opportunities for D’Agen Plums. He had a long standing interest in Asia, particularly Hong Kong and China (the Dairy Farm Group based in Hong Kong owned Simarloo from 1967 to 1970). Noel Sims knew that Chinese consumers preferred fruits with a high sugar content and that D’Agen plums matched this requirement. As a result he started to supply fresh D’Agen plums at the peak of their maturity to Hong Kong and mainland China. This new fresh product immediately caught on in Hong Kong and became the basis for a new global business.

‘Sugar plum’ exports began at Simarloo in the early 1980s and were copied by others in Australia and overseas. This led to Noel Sims going to California for 23 consecutive years during the northern hemisphere summer to pack and market ‘sugar plums’ under the Simarloo brand to Hong Kong on a counter-seasonal basis.

For further information about Noel Sims.

None of this would have been possible without international airfreight charters aimed at supplying ‘tree fresh’ fruit to Hong Kong. The early market success of ‘sugar plums’ and good returns enabled the use of air freight charters. Simarloo contracted Qantas to operate Boeing B747 freighters direct from Adelaide to Hong Kong. In the summer of 1996, five charter flights were operated from Adelaide to Hong Kong under a contract to carry up to 650 tonnes of fruit.

Simarloo also explored fresh airfreight exports of peaches and nectarines to France and the UK, both large peach and nectarine consuming markets. However, it was difficult to compete with closer South African suppliers in these markets.

Peaches and nectarines were not generally preferred by Asian palates other than the Japanese and Taiwanese. QFM (Quality Fruit Marketing), a Riverland stone fruit marketing business formed in 1995 by four Riverland stone fruit growers to enhance the marketing and returns. Peaches and nectarines were exported to Taiwan in the late 1990s to early 2000s until market access issues closed this market.

Since 2013, QFM has evolved into QFM Variety Management (QVM). QVM’s focus is now on managing stone fruit varieties exclusively for stone fruit breeders, ultimately gaining the QFM group a competitive advantage in the marketplace. The business is owned by the same people who own Quality Fruit Marketing.

The body, Summerfruit Australia coordinates fresh stone fruit activities nationally. In 2013–14, Australia exported 11,298 t of fresh stone fruit valued at $39.9M (69% peaches, 28% plums and 3% apricots), mainly to Hong Kong, United Arab Emirates and Singapore. During the same period, Australia imported 934T of fresh apricots from New Zealand.

Since the 1990s, there have been minor exports of fresh cherries, mainly to SE Asia countries, especially for Christmas and Chinese New Year celebrations. However this trade has been variable, being influenced by the strength of the $AUD, consistency of quality, and competition from other countries.

Dried fruits

South Australia’s dried fruit industry has been dominated by dried apricots (about 80% of dried fruit production), with other significant products being dried peaches, pears and prunes. Dried vine fruits (sultana, raisin, currants) are generally considered a separate industry.

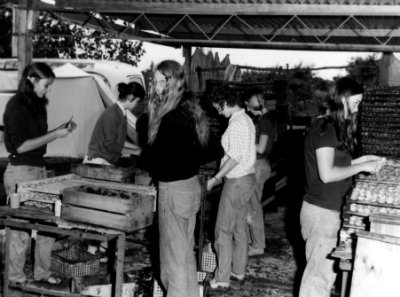

Hand cutting apricots for drying – Paringa 1972. Source: PIRSA image 103454

The appointment of the first South Australian London Wine and Produce Department Manager, Mr E. Burney Young in March 1894, commenced the development of export markets for dried stone fruits to the UK (along with jam, fruit pulp and canned products). He provided information about export opportunities in the UK and marketing issues associated with South Australian produce sent to London. A major issue was timing the arrival of South Australian dried and canned fruits in relation to peak periods of demand (influenced by availability of local fresh fruits). California dried fruit exporters were major competitors, supplying a superior product using higher levels of sulphur preservatives.

Displays of SA fruit products were presented at various exhibitions (Franco British Exhibition in 1907) and promotional programs run in regional cities. By 1907–08, South Australia was exporting almost 17,000 boxes of dried fruit and 3,300 cases of preserved fruits (more than 60% to the UK market). Exports of dried fruits expanded gradually to more than 20,000 boxes in 1915-16, but escalated to over 94,000 boxes as WW1 progressed, despite shortages of shipping space to the UK. The South Australian Government Produce Department also coordinated supply of jams and other fruit products to the UK War Office.

Beside direct sales to consumers mainly for baked products, dried fruits are used widely by bakery, breakfast cereal, confectionary and glace fruit manufacturers.

Sun drying fruit near Renmark – 1910. Source: State Library of SA File B 48116

Orchardists would normally hand cut, treat with sulphur dioxide, sun dry and roughly grade dried fruit on their properties. This dried fruit was then sold to numerous cooperatives or packing sheds which would store, clean, grade, process and package the dried fruit for sale to customers. Package size varied from bulk bins and large cartons (used by bakers and other food manufacturers) to small consumer snack size packets.

Moray Park Dehydrated Products Ltd set up a dehydration facility at Lyrup in the 1920s. This plant used a furnace to provide heat and fans to drive hot air along drying tunnels, producing higher quality prunes and raisins than traditional sun drying methods. Equipment was developed by Mr Milne Gibson on his McLaren Vale property, and supported by a trial dehydrator set up at the Berri Experimental Orchard in 1924. Moray Park Dehydrated Products then built their main processing plant in Lyrup in 1925 (other plants were proposed for Renmark, Berri and Waikerie, but insufficient capital was raised to fund this expansion). The Lyrup facility reached its maximum size in 1930 with 7 dehydrating tunnels, but experienced financial difficulty during the Great Depression and went into decline. Following several changes of ownership and restructures, the business was wound up in 1941. Further information about this facility is available from Lyrup Village – a Century of Association 1894–1994 by Alan Jones.

Most stone fruit districts had one or more dried fruit packers, often being cooperatives. The number of packers and marketers declined from the 1960s as the Australian dried fruit industry struggled to be cost competitive in world markets. By the early 1990s, retail prices of imported dried tree fruits from countries like Turkey were 50% to 75% the price received for Australian fruit. This resulted in decline, with the industry producing approximately 1,000 t pa between 1990 and 2005. Lengthening of the fresh stone fruit supply season also helped reduce dried fruit consumption.

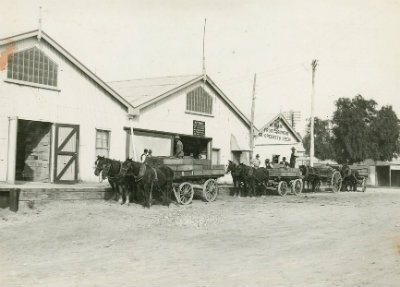

Delivering boxes of dried fruit to a packing shed at Renmark in 1940. Source: State Library of SA image B 22700

Many dried fruit processors either closed or amalgamated their business with other producers. The last large South Australian dried fruit processor was Angas Park Fruits at Angaston. Established in 1911, Angas Park used a wide range of innovative processing machinery and packing techniques to produce a wide range of consumer focussed products, but have now closed their processing operation. Sunbeam Foods based near Mildura are now the principal processor and marketer of Australian dried tree fruits.

Today, the Australian dried apricot market is dominated by imported fruit. In 2013-14, Australia imported 4,920t of dried apricots, mainly from Turkey and South Africa (Dried Tree Fruit Industry Advisory Committee Annual Report 2013–14). In 2006, Australian dried tree fruit growers produced their lowest volume in recent history, 650t.

Loading dried fruit for export onto a paddle steamer, Renmark 1940. Source: State Library of SA Image B 22696

Canning

South Australia’s early fruit canning industry commenced shortly after the introduction of canning technology in the 1860s and 1870s.

South Australian fruit canning businesses focussed on producing mainly apricot, peach and pear halves, sliced, and mixed fruit products in sugar syrup. Canned fruit provided consumers with dessert fruits year round. Initially canneries purchased fruit surplus to the fresh market, but as consumption increased and larger scale canneries were established in the Riverland, dedicated orchards with varieties suited to canning were planted.

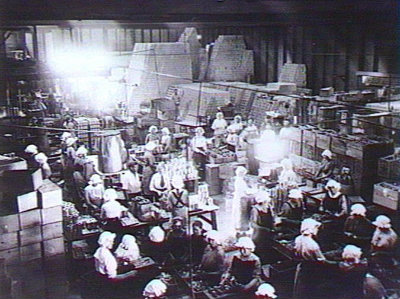

Interior of Sage’s fruit preserving cannery at Nuriootpa in 1915. Source: State Library of SA Image B 45876

In the early 1900s, numerous small canneries were located in Adelaide and across various fruit growing districts. Some examples included:

- Adelaide suburbs (J. Brooker & Sons at Croydon, Mumzone Products Ltd, St Peters)

- Nuriootpa – Sage’s Cannery was operating in 1915, Mr H. Warnecke was MD in January 1950 and it closed in 1960

- Angaston – Trescowthick Bros were operating a large canning operation in 1919.

- Clare – Clare Preserving Company (established 1883).

Adelaide based canneries obtained fruit from local fruit growing districts, while increasing quantities were being supplied from the Riverland. By 1950, about 80% of fruit for Adelaide based canneries was being transported by rail from the Riverland. Frequent delays in rail freight services often provided Adelaide canners with poor quality bruised fruit with high wastage levels, resulting in poor returns to growers.

Following several years of difficulties, Riverland fruit growers lobbied the Premier, Tom Playford about problems with rail services. A Fruit Transport Committee with staff from the Canners Association, Department of Agriculture Horticulture Branch (Mr Strickland), SA Railways, and the Road Transport Board was formed in 1949 to address these problems. Following trials, SA Railways upgraded Riverland services to 3 trains per week, and reduced connection delays at Tailem Bend. Road freight was also allowed to operate on days trains were not running. In 1954, refrigerated rail trucks were also introduced for fresh fruit being transported to Adelaide.

Several significant Riverland canneries were established, mostly during and immediately after WW2, and quickly grew to dominate the industry. These businesses often changed their names as they went through a restructure or changed ownership.

The Berri Fruit Juices Coop Ltd was formed in 1948. This company produced a wide range of products including citrus juices, citrus oil, apricot pulp, canned apricots and various fruits, apricot nectar, tomato juice and cordials. In 1948 it began exporting canned products to the UK, and later Malaya, Hong Kong, India, Egypt, Holland, Canada and New Zealand. This facility specialised in canning fruit and vegetable juices, and went through numerous changes of structure and ownership before closing in 2010.

A cannery was established at Taplan Rd Loxton in 1950 through a merger of J. Brooker & Son and the Robern Dried Fruit Co. It canned apricot, tomato, peach, pear, nectarine, beetroot and carrot, and owned 60 acres of asparagus at Lyrup, which was grown for canning. This cannery processed the first stone fruits produced by the fledgling Loxton War Service Land Settlement area and was subsequently bought out by Riverland Fruit Products Cooperative at Berri.

The Moray Park cannery at Renmark was established in the early 1950s. It operated successfully for many years, canning apricot, peach, pear and asparagus. This company also developed frozen fruit products in the early 1950s, including frozen airline meals. The company was restructured several times, received significant government assistance in the 1970s, but in September 1980 it was placed in receivership.

Rapid expansion of the canned fruit industry occurred immediately after WW1 and WW2. By 1931, Australia’s canning fruit industry was producing 180,000 dozen 30 oz cans of apricots, 1,367,000 dozen cans of peaches, and 205,000 dozen cans of pears. This was despite the reduced spending powers of consumers caused by the Great Depression.

During WW2, canneries switched a significant proportion of canning capacity to production of canned vegetables, dehydrated potatoes, soup, and meat products to meet demand from their main customer, the UK War Ministry.

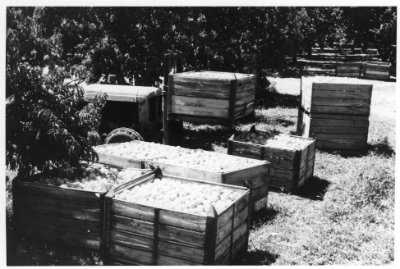

Harvested peaches ready for loading and transport to the cannery. Renmark 1972. PIRSA image 103565

Immediately post WW2, demand for and production of canned fruit declined. However as the UK economy recovered through the 1950s, demand for canned fruits increased rapidly, and plantings were expanded to meet needs. Between 1952 and 1959, South Australian peach plantings doubled, with many being placed onto poorly drained soils, resulting in poor fruit size and quality. The superior canning quality of clingstone varieties saw rapid decline of dual purpose free stone varieties. By the 1960s, canning peach growers had a choice of about 15 varieties, using a spread of maturity times to aid harvesting.

For many years, the UK was Australia’s main market for canned fruit with trading favour being given to Commonwealth countries. In 1958, the UK imported 7.5 million standard cases of peaches, pears and apricots, about 60% of the world’s trade in these canned fruits. Australia supplied 43% of these UK imports while South Africa provided 34% and the USA 8%.

In 1958, Australian production of canned peaches, pears and apricots was 5.7 million cases (standard cases of 24 No 2 1/2 cans).

Following the UK joining the European Union in 1973, export sales of canned fruit to the UK began declining. The dramatic reduction of sales in the UK caused significant downsizing of the Australian fruit canning industry.

Changing domestic consumer preferences contributed to decline of canned fruit sales in the 1970s and 1980s. Improved storage, refrigerated road transport, and new varieties expanding the fresh fruit season gave consumers better supplies of fresh stone fruit, resulting in decline of the canning industry.

During the early 2000s, Riverland canned peach growers sold some fruit to SPC Ardmona at Shepparton. However the cost of road transport and over production in the Shepparton district put Riverland growers at a disadvantage, and production of canned peaches has virtually ceased in South Australia.

Jam and chutney products

From the 1860s, numerous local businesses produced a wide range of jams and chutneys in each of the main stone fruit growing districts. Frequently they used lower grade fruit not suitable for the fresh market. Many of these canned or bottled jam and chutney products were marketed in the UK and European countries, especially in the period 1900 to 1960. Jam and chutney consumption has declined since the early 1970s, and this sector of the industry is now quite small.

There were numerous smaller jam and chutney manufacturers, mainly in the suburbs of Adelaide (e.g. J. Brooker and Sons at Croydon).

One of the most recognised and first large scale South Australian jam manufacturer was Glen Ewin at Houghton. Scottish horticulturalist George McEwin purchased a property near Houghton in 1844 and developed a vineyard, winery and orchards on it. He commenced making jam there using his own fruit in 1862, and later purchased fruit from numerous other growers. Later Glen Ewin also operated a significant jam processing plant at College Park employing more than 70 staff.

Initially Glen Ewin packaged jams into glass jars, but in 1867 pioneered using cans manufactured in Adelaide by Alfred Simpson. The Glen Ewin business continued to market a wide range of jams and sauces in Australia, UK and other countries. The company was managed by McEwin family members until 1988 when the Houghton factory was closed. The Glen Ewin name has been subsequently used by other manufacturers (Glen Ewin Fine Foods and Henry Jones IXL). The Glen Ewin homestead at Houghton has subsequently been developed as a reception centre.

For further information visit Glen Ewin jams or SA Memory.

Another major South Australian jam manufacturer is the Hahndorf based Beerenberg label established by the Paech family. It began selling “home made” jams from a roadside stand in 1969, and now operates a major manufacturing facility at Hahndorf employing about 50 people. Beerenberg produces a wide range of jams, marmalades, chutneys, sauces, pickles, dressings, dessert toppings and olive oils. Beerenberg’s label has become internationally recognised through supply of portion size jars and foil packs of jams to premium hotels and airlines across the Asia-Pacific region. For further information visit Beerenberg.

There are also a number of nationally recognised jam brands that have been manufactured in the eastern states, including Henry Jones IXL, Cottee’s and Cadbury Schweppe’s Monbulk. These have sourced the majority of their fruit from eastern state orchardists.

Glacé fruit

The manufacture of glace fruit has been a small but important part of the stone fruit industry for many years. The process of steaming, soaking in sugar syrup, then drying the fruit is commonly used for apricots, peaches, figs, pears, cherries, oranges, pineapple, citrus peel and ginger.

Glace fruits have been produced by numerous South Australian manufacturers. The largest was Toora Vale at Monash, which was subsequently purchased by Simarloo. Under Simarloo’s management, approximately two thirds of its glace fruit production was exported to the USA. Cheaper imports have resulted in a decline of Australian production of glace fruits. Simarloo ceased production of glace fruit in 2010, being influenced by the high value of the A$ and increasing input costs. Glace Park based at Angaston was also a significant glace fruit producer for many years.