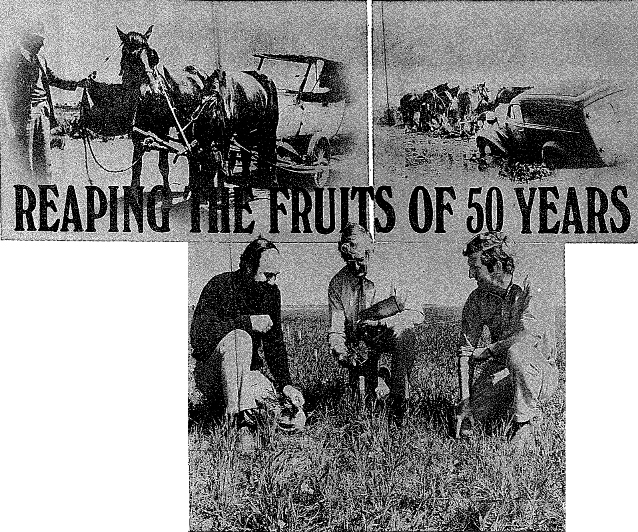

Reaping the Fruits of 50 Years

Top Left: Here's how one West Coast farmer beat petrol rationing in World War II. The photograph showing Department of Agriculture adviser Mr. Peter Angove examining horses was taken in Arno Bay in 1940.

Top Right: Mr. Angove's government-issue Chevrolet panel van, bogged on the Lock – Rudall road in 1939.

Middle: Senior District Agronomist for the Lower North district, Mr. W.A. Michelmore centre, with Two Wells farmers Mr. Neville Sharpe left, and Mr. Robert Hart.

From small beginnings in a harsh environment in 1926, district agricultural advisers of the SA Department of Agriculture and Fisheries have played a unique role in helping SA farmers develop a dry land farming system and a technology which is now the best in the world for producing food and fibre from semi-arid lands.

The Advertiser Saturday Review 2 October 1976

Page 21

Rural Affairs Editor

Jim McCarter reports

Fifty years ago this month, the staid columns of SA Journal of Agriculture announced that five men had been appointed by the government as agricultural instructors.

It was a brave new venture by the then tiny Department of Agriculture. In the pre-Depression era (and for many years afterwards) SA's prosperity was anchored to agriculture.

The State's manufacturing sector was in its infancy and mining almost dead after the booms of the mid-1800s.

In those days, farming systems were simple – and totally exploitive. Wheat cropping dominated the scene – an endless pattern of crop and fallow that wreaked a terrible toll on soil structure and stability.

Livestock production was minimal, other than in those areas unsuited to cropping. It was against this background that the department appointed its first instructors, charging them with the task of "promoting general agricultural practices in districts in which they were placed."

No one then could ever have predicted what those appointments would lead to over the next 50 years.

The five pioneers were:

- Messrs' R.I. (Rowland) Hill

- E.I. Orch

- H.D.M (Monty) Adams

- R.D. Griffiths

- E.S. Alcock

to be followed within a few years by W.H. Brownrigg, W.C. Johnson and H.Follet.

There have been only 34 successors to these men, including the present 14 who hold district positions.

Collectively, the district agricultural advisers, or agronomists, as they are now known, have been one of the greatest influences on agricultural growth in South Australia.

They have been at the forefront of every technological change in the past 50 years, and it has been largely through their perseverance, dedication and skills that those changes have been adopted by farmers.

The rewards of their efforts are reflected in the State's rural statistics:

- Gross value of rural production up from $28.6m in 1930-31 to $702m in 1974-75.

- Total cereals production up by 131p.c. from 1.179m. Tonnes to 2.732m. tonnes in 1974-75

- Sheep numbers almost trebled, from 6m in 1930/31 to 17.2m in 1976

- Beef cattle up six-fold, from 300,000 to 1.94m this year.

None of the pioneering advisers is alive today, but the names of most of them are still revered in rural circles.

All colourful individualists with one common bond linking them - dedication to their job.

It is a trait which has characterised every district adviser appointed to this day.

As Port Lincoln's district agronomist Mr Keith Holden explains, "You certainly don't take the job on because of money or working conditions."

"But there's tremendous job satisfaction in the responsibility, the recognition from the department and the farming community, and in being able to help farmers and others, either as individuals or groups."

Jack McAuliffe recently retired as SA.'s principal agronomist and a man who had many years in the field agrees.

"Apart from the straight-out job satisfaction, there is a great degree of freedom as well- you are your own boss within your district."

"Your boss, in fact, becomes the farming public, the people you serve."

"If the job became regimented with overtime payments and penalty rates, I believe it would lose the spontaneity and a lot of dedication which has characterised it over the past 50 years."

Most of today's agronomists are, like Ken Holden, youngish men, well qualified and vastly better trained in both advisory and extension work rather than their predecessors.

They are much more specialists today, a change that has accelerated since the 1950s to keep pace with the rapidly changing demands of the industry.

"The whole department is more specialised in fact," says Arthur Tideman, head of the agronomy branch. "Before 1950, the district agricultural advisers were generalists in the broadest sense of the word, expected by both farmers and the department to give advice on any topic."

"Now we have specific branches for livestock, soils, animal health, dairying, economics, extension, research and of course agronomy (crops and pastures)."

It was in recognition of this trend that the term "district agricultural adviser" was abandoned 5 years ago in favour of 'district agronomist." "Our men in the field today specialise in crops and pastures, and rely heavily on the backup services of other specialists," Mr. Tideman said.

The modern district agronomist not only gives technical advice to farmers on modern developments affecting them, but also integrates this with rural sociology and human behaviour sciences.

In the early days, advice was centred on particular individual problems; today it's considered more in terms of the whole operation.

"Farmers are asking more and different questions than they did in the past," principal agronomist Glynn Webber said.

"They don't want to know just what crops to grow or what insecticide to use, but what are the profitability and marketability aspects of the crop, and what benefits will an insecticide bring, what will it's environmental effects be, what are the financial benefits of using it or not."

"They want more information on management decisions and how to grow different new crops such as peas, beans, sunflowers etc. to smooth out the ups and downs of traditional cereals."

"Farmers are applying highly specialised techniques today, and they're using increasingly sophisticated machinery and plant to do so."

"They are less and less interested in production per se, as was the case in the past."

District agronomists are also being called on to supply up to date information about crops for governments, marketing organisations and agri-business.

This responsibility puts added pressure on their time.

"It's very rewarding work, but it is time consuming in a job where the normal workload is such that often you are already hard pressed to do the best possible job," Mr Holden admits.

"At times I think the department is understaffed to cope with a lot of this added work."

It is not a job for clock watchers.

District agronomists like their fellows in other branches, don't get paid overtime or penalty rates.

But for farmers, office hours don't apply and thus the agronomist's telephone can start ringing at 6 a.m. and not stop until 9 p.m.

"Certainly your family life suffers," says Mr. Holden.

"It worries me that before I know where I am my family will have grown before I've been able to do what I want to do for and with them."

Although the dedication of the job has carried over to modern times, few would deny that it's most colourful era occurred pre-1950 when officer had to rely almost entirely on their own individual resources to help farmers.

"They flew virtually by the seat of their pants," says Glynn Webber.

Peter Angove, who started as a district adviser early in the 1940s has vivid recollections of the era. "You did anything and everything to help the farmer," he says.

"If he needed help lumping bags of super, you gave it; if his wife didn't know how to prune roses, you showed her how or did it for her; if horses' teeth needed filling or lambs needed to be marked, or a colt cut – you jolly well did it."

The help given wasn't always "spot on."

Peter well recalls treating a horse for colic by dosing it with a bottle of turpentine and a tablespoon of linseed oil, when the proper cure was a bottle of linseed oil and a tablespoon of turpentine. "Fortunately for me it lived," he said.

On another occasion he rang a farmer to tell him he'd be out to treat a sick cow in place of the regular adviser, Wes Johnson, who had been called to Adelaide.

"When I got there, I found he had shot the cow simply because it wasn't Wes who'd come to treat It." He said, "I felt terrible."

A famous story around the district is that of district adviser Cec Gross, who, without ever having ridden a motorcycle in his life, was given the department's then newly acquired Harley Davidson to make a trip to Minlaton for a farmers' meeting.

"It took Cec a full day to get the brute to Minlaton and another day to get back on it," Mr Angove chuckled.

Mr Gross incidentally, was the longest serving district agricultural adviser, when he retired in 1974. He'd spent 28 years in the job.

Bill Brownrigg, who was appointed soon after the first five instructors, served almost as long.

Shocking roads were a hazard in many areas pre-war. One of the worst was the 64 kilometre stretch between Yeelanna and Lock, on Eyre Peninsula. Three hours was considered a good time to cover this.

"The department vehicle I used then was a Chevrolet panel van," Mr. Angove said.

"A regular chore every Saturday morning, in my own time of course, was to drop the front wheels off, remove the steering and springs, and straighten the axels using a local hydraulic press."

"Believe it or not, I could do the whole job, and reassemble in two hours flat."

Not all farmers appreciated having men to advise them in the early days.

In 1931, for example, Millicent farmers issued a scathing condemnation of the Government's 'extravagance' in maintaining the then agricultural instructors.

"If people who want to advise and help look to the successful farmers in their own neighbourhood, they would fare better than by running along to government advisers," thundered the then secretary of the Millicent agricultural Bureau, Mr. E.J. Mitchell.

Fortunately for SA, such opinion was isolated.

It was ironic that the criticism came from a branch of the Agricultural Bureau for it was the bureau that provided the structural organisation that allowed the early advisers to perform so well.

The bureau was (and still is) a self-help organisation created by farmers, and for many years SA was the only state to have such an organisation.

Through regular branch meetings, the early advisers were able to get together with farmers to spread the message of progress.

The older generation of advisers nominate the advent of ley farming as the greatest single development of agricultural development in SA in the past 50 years. It's not difficult to see why.

The standard wheat-fallow rotation of the 1920s "flogged hell out of the soil" to quote one adviser. Farmers sowed their crops with superphosphate after a year of fallow which they hoped would have conserved water and increased nitrogen.

Their only means of traction was the draught horse, and thus crop sowing was a slow business, requiring ploughing and weed control and weed control to be completed before the critical sowing period after the first autumn rains.

While the wheat-fallow rotation suited the farmers' labour needs, it depleted the soil of organic matter, reduced its fertility and ruined its structure, leading to steady decline in crop yields.

By 1930, this system was near collapse.

The district agricultural advisers were among the first men to pinpoint the root causes of the problem, but convincing the farmers was a different matter.

Fortunately nature came to their aid.

Driven by strong north winds, the powdered top soil from thousands of hectares of land started to move in the 1930s, blanketing the state with massive summer dust storms.

These forcibly brought home to everyone that something was very wrong.

In the early 1940s, the department's newly appointed soil-conservator, Mr. Bob Herriot, "stumped" the sate urging farmers to "throw their harrows down the creek" and stop burning the stubbles.

"I well remember him telling to a meeting of Kimba farmers to do this," Mr. Angove Recalls. He was then district adviser at Port Lincoln.

"The farmers went home from the meeting infuriated. Next morning, still thoroughly angry, they put the torch to all their stubbles in defiance of Herriot's advice. You couldn't see Kimba for the smoke."

"Herriot's only comment was: 'Well at least I made an impression.'"

But the seeds of change had been sown, and in the 1940s they started producing a harvest.

The 'harvest' was ley farming – an integrated system of cereal cropping and livestock production where cropping alternated with pasture leys.

Subterranean Clover, first used in the 1930s, and the discovery in the late 30s of the value of Barrel Medic for the drier alkaline soils of the cereal belt were the keys to ley farming.

The legumes, self-regenerating annual species, reduced the need for fallowing, returned organic matter to depleted soils, helped tie the soil down and improve its structure, boosted fertility and gave increased yields of cereals and livestock.

Again, it was the district agricultural advisers who had the task of persuading farmers to change their traditional system to grow legumes.

Several factors helped. Tractor power became available, making it possible to plough and sow in the autumn. Livestock industries became viable. And at the same time, the seed of pasture legumes became commercially available. Even so, it took 20years to have ley farming adopted throughout the state.

"The system is famous, because it is stable, non-exploitive, and allows major increases in crops and livestock," says Glynn Webber. "It is now acclaimed as being the worlds most advanced technique for farming semi-arid lands."

Mr Ted Carted, a lecturer in agronomy at the Waite Agricultural Research Institute, has estimated the annual value of soil nitrogen accruing from grazed leguminous pastures exceeds $60m a year.

In recent years, the SA ley farming system has achieved international recognition. So have the skills of district agronomists. This fact was highlighted when the department received and accepted an invitation to establish a demonstration farm at El Marj in Libya nearly 3 years ago.

Three district agronomists plus a soils officer were seconded from SA in a joint operation with the State farmer volunteers to create the farm and apply ley farming techniques with the aim of bringing large areas of Libya into agricultural production.

It is a remarkable venture whose progress is being closely followed by many other Middle Eastern countries with similar climates and soils.

Besides drawing the international spotlight on SA, it is opening up many avenues for future trade and development.

It is indeed a far cry from those early days when five men took the first tentative steps to help bring about the fulfillment SA's agricultural promise.

Download original article ()